Summary

The History of Bible Translation in China can be divided into four periods:

- The Era of Sporadic Bible Translations: 635–1800

- The Struggle for the Authoritative Chinese Bible: 1800–1920

- The Rise of the Authoritative Chinese Bible: 1920–1980

- The Marginalization of the non-Chinese Bibles: 1980–present

The Era of Sporadic Bible Translations (635–1800) is characterized by irregular missions from the Middle East and Europe to China, often in combination with trade activities. The missionaries were a subgroup of a larger set of people who had established contact with the Chinese for various reasons. The first missionaries who migrated to China were Nestorian Christians in A.D. 635. They moved to China via the ancient Silk Road together with other Middle East traders. The Muslim Huí 回 people, whose population is distributed unevenly throughout Modern China, are descendants of these traders. The Nestorian missionaries translated several books of the Old and New Testament into Middle ChineseLinguists divide the history of Chinese into five periods:

Old-Chinese 上古文 B.C. 1000-0

Middle-Chinese 中古文 A.D. 0-900

Old-Mandarin 近代汉语 1000-1200

Middle-Mandarin 近代汉语 1368-1644

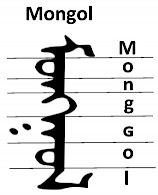

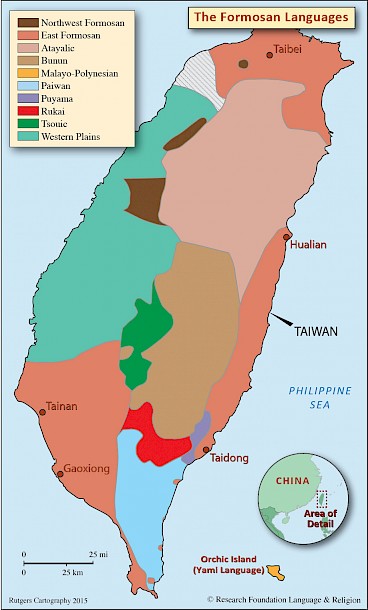

New-Mandarin 现代汉语 1800-today. No manuscript survived to the present day, but the Nestorian stela of Xī'ān referred to the translation of Bible portions. These portions were probably secondary translations based on the ancient Syriac Bible, the Peshitta. During the Mongol empire in the medieval period, Pope Nicholas IV appointed John of Montecorvino as his special envoy to the Mongol court. Venetian trader Marco Polo traveled to China at approximately the same time as John, although he was more motivated by commercial gains than religious interests. In 1307, John of Montecorvino translated the Psalms and the New Testament into Old Uyghur, the language used by the Mongol elite. No manuscript was preserved, but John mentioned his achievements in two letters to the Pope. The third language into which portions of the Bible were translated was the Formosan Siraya language. During the Dutch occupation of Taiwan in 1661, reformed preacher Daniel Gravius translated the Gospel of Matthew into Siraya. As a member of the Dutch Reformed Church clergy, he was employed by the Dutch East India Company, which was a chartered trading company. Dutch missionary activities had impacted the indigenous people until the early eighteenth century. None of three aforementioned Bible translations had any lasting effect nor were circulated widespread as there was no strategic plan to push these efforts. They were drops in the bucket (Isaiah 40:15), yet they were imperceptible beginnings that laid claim to Christianity’s ancient roots in China.

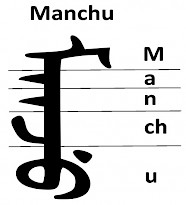

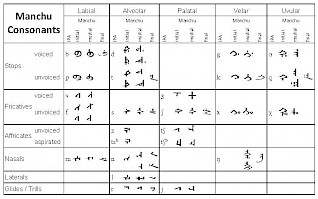

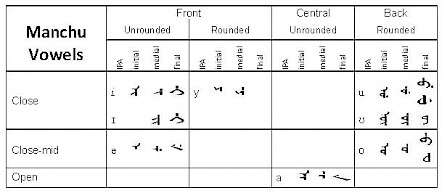

The nineteenth century saw the Struggle for the Authoritative Chinese Bible (1800-1920). This struggle depended on another conflict: the choice of the lingua franca (common language) that could unify the Chinese empire. The Manchu government used the speech of BěijīngIt was called Guānhuà 官话 or language of the Mandarins. as the language in which daily business was conducted. However, only a limited number of people in the populous south could speak this language fluently. Classical Chinese enjoyed prestige in the nineteenth century, but like Latin, nobody spoke it as a native language. Over 50 years, the Protestant missionaries had translated five versions of the Classical Chinese Bible. None of these endeavors, however, appealed to Chinese Christians, for which we might present two reasons. First, the Bibles were translated in a dead, albeit prestigious, language. Second, there was no consistent language policy behind Classical Chinese to promote it as a vehicular language for ordinary people. In the later nineteenth century, it became increasingly clear that the speech of Běijīng might assume the role as the lingua franca. Frustrated by the lack of an authoritative Bible, in 1890, the Protestant missionaries established three interdenominational translation committees: one for the high register of Classical Chinese, one for its low register, and one for Mandarin, the speech of Běijīng. Only the Mandarin committee survived the long translation process of 30 years; the classical committees were dissolved in the meantime. These decisions were influenced by political developments. At a national conference in 1913, the young Republic of China decided to adopt the speech of Běijīng as its national language. When the Mandarin committee completed their work and published the Chinese Union Bible in 1919, the timing could not have been better. Between the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Protestant missionaries also translated portions of the Bible into approximately 26 Chinese dialects. These Bibles were circulated locally, and they accommodated the needs of the nascent church communities until the authoritative Chinese Bible arrived. Moreover, Bible translations into three important minority languages were commenced or achieved in the nineteenth century: Manchu (1822), Tibetan (1862), and Modern Uyghur (1898). Fascinating stories are attached to each of these projects.

The Rise of the Authoritative Chinese Bible (1920-1980) correlates to the rise of Mandarin Chinese as the national language. During the Republican period (1911–1949), preparations for the promotion of Mandarin Chinese were made; however, real changes were only implemented during the Communist era after 1949. According to Chinese scholar Zhōu Mínglăn 周明朗See Zhōu (2003, 2013)., the Chinese language policy followed two models of nation-state building: the Soviet model (1950–1980) and the Chinese model (1980–present). In the 1950s, the Chinese government imposed a multilingual language order in which Mandarin Chinese became the lingua franca of Chinese dialect areas, which was supplemented by the local dialects where necessary. A minority language became the lingua franca of an ethnic autonomous area, and Mandarin Chinese was spoken as a complementary language. During this phase of nation-state building, Mandarin Chinese marginalized all other Chinese dialects. The last Chinese dialect in which a Bible portion was translated was the Teochew 潮汕 dialect (Southern Mǐn) in 1922. This marked the beginning of a gradual process in which all dialect translations fell into disuse while the Chinese Union Version rose to prominence. Exceptions are the Hokkien and Hakka dialects, which are spoken by a sizable diaspora abroad, and for which the Bible Society of Taiwan published revised Bible translations in 2008 and 2012.

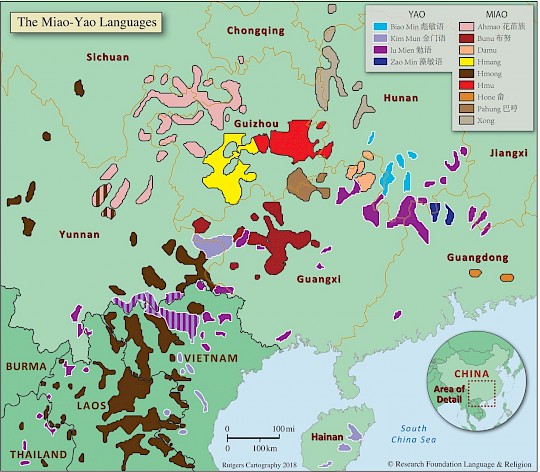

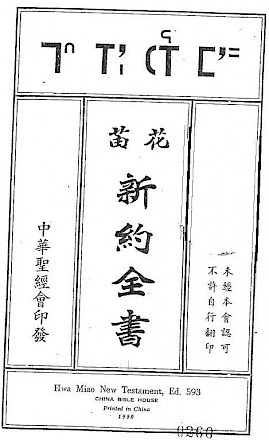

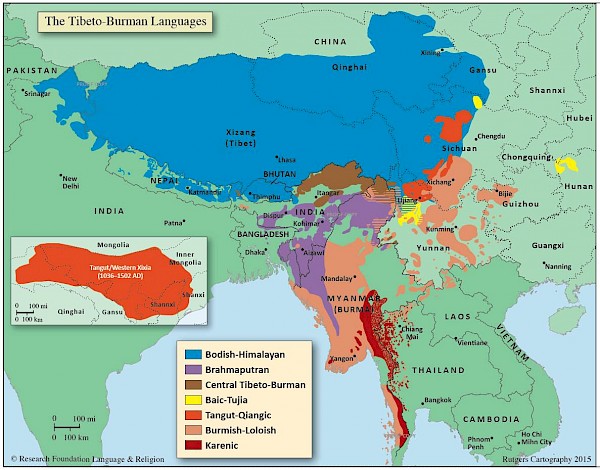

The Marginalization of the non-Chinese Bibles (1980-today): The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) destroyed the multilingual language order, but a reversion to the old order seemed impossible. The government amended Article 19 of the Constitution in 1982 and made Mandarin Chinese the lingua franca (Pŭtōnhuà) of all nationalities. This led to the Chinese model of nation-state building with a monolingual language order in place. The transition was accentuated by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the introduction of economic reforms. Labor and household registration rules were reformed; people were no longer required to work in the location where they were born. This led to a strong increase of internal migration from poor rural areas to richer coastal areas. In particular, young people left the countryside, whereas elderly people stayed behind. Some observers estimatedSee Zhōu Mínglăn (2013, p. 25). that the number of migrants increased to 100 million in the 1990s and to 200 million in the 2000s. that the number of migrants increased to 100 million in the 1990s and to 200 million in the 2000s. The fusion of new populations boosted demand for Mandarin Chinese as the lingua franca at the expense of the Chinese dialects and minority languages. Furthermore, economic development created the need for a common language for communication, thus alienating minority people from their mother tongue, which is now perceived as a negative instead of a positive. As a result, minority languages began disintegrating at an alarming pace. This trend was exacerbated during 2010–2016 due to the emergence of mobile communication (the surface language of mobile devices is Mandarin Chinese) and the boom of construction projects (part of the land population was relocated into tower buildings in Hàn areas where the dominant language is Mandarin Chinese). Foreign missions came to China in the 1990s to translate the Bible in minority languages. Some of these projects have borne fruit in the past 10 years and added about five new languages to the set of languages with Scriptures. Yet, under prevailing obstructive conditions, the momentum for new translation projects is irrevocably lost; therefore, efforts to reach out to minority people will increasingly involve the Chinese Union Bible. There are a few exceptions though. The Flowery Miao (Ahmao)Spoken in Guìzhōu Province., Flowerly LisuSpoken in Yúnnán Province., NasupuSpoken in Yúnnán Province. and NuosuSpoken in Sìchuān Province. languages show rigorous use of the Bible by Christians. The assimilation of these languages to Mandarin Chinese is expected to be slower than other languages. In Taiwan, Mandarin Chinese has risen to a dominant position in public life as well. The Formosan languages are endangered to various degrees. Bible portions were translated in 10 minority languages over the past 60 years; the translation projects proceeded without repression. However, Taiwan’s economic development has undermined the use of minority Bibles in a similar way.

Over the past 1,400 years, missionaries have translated Bible portions in 70 languages. The following table categorizes these languages along their genetic affiliation.

|

Group/Family |

Translated Languages |

|---|---|

|

Sinitic |

29 |

|

Altaic |

5 |

|

Miao-Yao |

4 |

|

Tai-Kadai |

6 |

|

Tibeto-Burman |

14 |

|

Austro-Asiatic |

2 |

|

Formosan |

10 |

Table 1: Language groups with Scriptures in China

More than 38 Christian organizations based in 14 countries and affiliated with 11 denominations participated in Bible translation projects. Organizations from the United States of America and Great Britain have contributed most to Bible translation in China. The following table classifies the contribution toward Bible translation in China according to the Christian organizations, their denominations, and their country of origin.

|

Denomination |

Organization |

Country of Origin |

Translated Languages |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Orthodox |

Syrian Orthodox Church |

Syria, Iraq |

1 |

|

|

Russian Orthodox Church |

Russia |

2 |

|

Catholic |

Roman Catholic Church |

Italy |

3 |

|

Three-Self |

China Christian Council/Three-Self Patriotic Movement |

China |

6 |

|

Anglican |

American Episcopal Mission |

USA |

3 |

|

|

Church Missionary Society |

UK |

6 |

|

|

Church of England Zenana Missionary Society |

UK |

1 |

|

Reformed |

Dutch Reformed Church/Mission |

Netherlands |

2 |

|

|

Swedish Missionary Society |

Sweden |

1 |

|

Congregational |

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions |

USA |

4 |

|

Presbyterian |

English Presbyterian Mission |

UK |

4 |

|

|

American Presbyterian Mission |

USA |

10 |

|

|

Canadian Presbyterian Mission |

Canada |

2 |

|

|

Presbyterian Church of Taiwan |

Taiwan |

2 |

|

Baptist |

Baptist Serampore Mission |

UK, India |

1 |

|

|

Conservative Baptist Foreign Mission Society |

USA |

1 |

|

|

American Southern Baptist Mission |

USA |

2 |

|

|

American Baptist Missionary Union |

USA |

3 |

|

Methodist |

American Methodist Episcopal Mission |

USA |

2 |

|

|

American Southern Methodist Episcopal Mission |

USA |

1 |

|

|

United Methodist Mission |

UK |

2 |

|

|

United Methodist Free Church |

UK |

1 |

|

|

English Wesleyan Mission |

UK |

1 |

|

|

Bible Christian Mission |

UK |

1 |

|

Pentecostal |

Dutch Pentecostal Missionary Society |

Netherlands |

1 |

|

Interdenominational |

Anonymous Individuals |

--- |

3 |

|

Asian Christian Service |

USA |

1 |

|

|

|

London Missionary Society |

UK |

6 |

|

|

China Inland Mission (until 1964) |

UK |

11 |

|

|

Overseas Missionary Fellowship (after 1964) |

UK |

1 |

|

|

Basel Missionary Society (until 2001) |

Switzerland |

1 |

|

|

Institute for Bible Translation |

Russia |

1 |

|

|

Research Foundation Language and Religion |

Germany |

4 |

|

|

Vandsburger Mission/Marburger Mission |

Germany |

1 |

|

|

Moravian Church Mission |

Germany |

1 |

|

|

Zentralasien-Gesellschaft |

Germany |

1 |

|

|

Summer Institute of Linguistics/Wycliffe Bible Translation |

USA |

5 |

|

|

Bible Society of Taiwan |

Taiwan |

7 |

|

|

United Bible Societies |

--- |

8 |

Table 2: Bible Translation by Christian Missions in China

Chinese dialects (28)

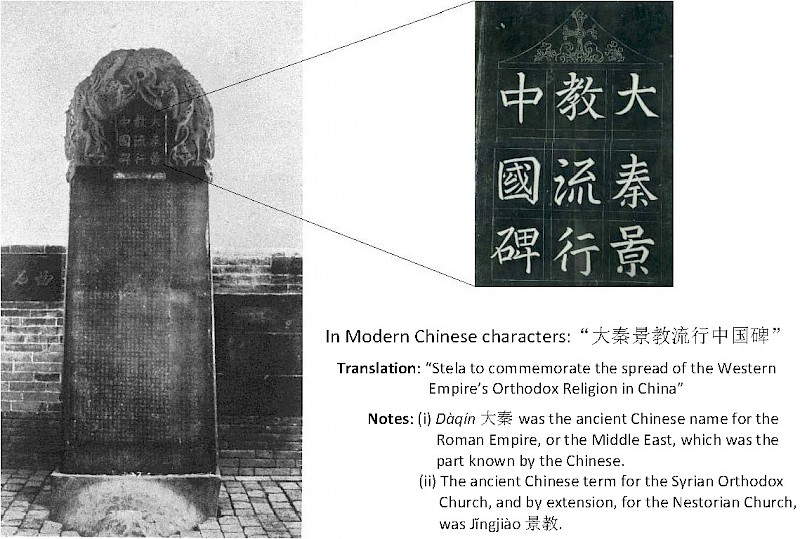

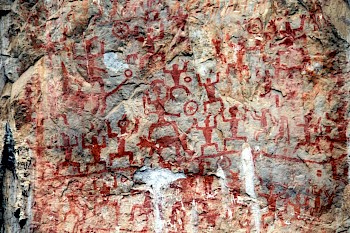

Orientalist Paul PelliotFrench Orientalist Paul Pelliot 伯希和 (1878-1945) discovered many of the Dúnhuāng manuscripts.Parts of the Bible were first translated by NestorianNestorius (386–450), Patriarch of Constantinople, emphasized the disunion of the human and divine natures of Christ. His teachings were condemned as heretical by the Council of Ephesus (431). As he was separated from the Western Churches, he associated himself with churches in Syria, Iraq, and Persia to form the Church of the East. Some historians have warned, though, that the churches of Syria, Iraq, and Persia had not unequivocally embraced Nestorius’s monophysitism and that the Church of the East should not be identified with the doctrine of Nestorius (see Hofrichter 2006). Christians after A.D. 635 when the Syrian missionary AlobenAloben (Chinese: Āluóběn 阿罗本) is known exclusively from the Nestorian Stela in Xī’ān. He was probably a Syriac speaker from Persia. His name might be a transliteration of the Semitic “Abraham.” came to Cháng’ān (today’s Xī’ān). A stela was found in Xī’ān in 1625 commemorating Christian activities in China during the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907). The stela was erected in A.D. 781, after the Nestorian missionaries had evangelized the local population for some time. In A.D. 720, China became an ecclesiastic province of the Church of the East, under the name of Beth SinayeSee Wilhelm Baum and Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London: RoutledgeCurzon.. The Church of the East in China disappeared after the fall of the Tang dynasty in A.D. 907. The text on the stela mentions “Scriptures were translated,” which unequivocally refers to the translation of some portion of the Bible. However, no Bible translation has been preserved.

Orientalist Paul PelliotFrench Orientalist Paul Pelliot 伯希和 (1878-1945) discovered many of the Dúnhuāng manuscripts.Parts of the Bible were first translated by NestorianNestorius (386–450), Patriarch of Constantinople, emphasized the disunion of the human and divine natures of Christ. His teachings were condemned as heretical by the Council of Ephesus (431). As he was separated from the Western Churches, he associated himself with churches in Syria, Iraq, and Persia to form the Church of the East. Some historians have warned, though, that the churches of Syria, Iraq, and Persia had not unequivocally embraced Nestorius’s monophysitism and that the Church of the East should not be identified with the doctrine of Nestorius (see Hofrichter 2006). Christians after A.D. 635 when the Syrian missionary AlobenAloben (Chinese: Āluóběn 阿罗本) is known exclusively from the Nestorian Stela in Xī’ān. He was probably a Syriac speaker from Persia. His name might be a transliteration of the Semitic “Abraham.” came to Cháng’ān (today’s Xī’ān). A stela was found in Xī’ān in 1625 commemorating Christian activities in China during the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907). The stela was erected in A.D. 781, after the Nestorian missionaries had evangelized the local population for some time. In A.D. 720, China became an ecclesiastic province of the Church of the East, under the name of Beth SinayeSee Wilhelm Baum and Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London: RoutledgeCurzon.. The Church of the East in China disappeared after the fall of the Tang dynasty in A.D. 907. The text on the stela mentions “Scriptures were translated,” which unequivocally refers to the translation of some portion of the Bible. However, no Bible translation has been preserved.

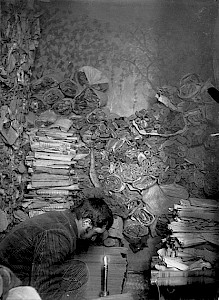

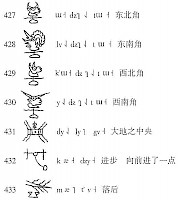

In 1907, Nestorian documents were found in the Mògāo Caves 莫高窟The Mògāo Caves 莫高窟 are located 25 km southeast of Dúnhuāng 敦煌 and contain examples of Buddhist fine art spanning a period of 1,000 years as well as a large number of documents in various languages such as Chinese, Tibetan, Uyghur, Sanskrit, and Sogdian. In 1907, Nestorian Christian works were found in the Caves. The International Dúnhuāng Project was established by the British Library in 1994, and it is a cooperative effort of 24 institutions from 12 countries to conserve, catalogue, and digitize the manuscripts found there. in Dúnhuāng敦煌Dúnhuāng 敦煌 is a county-level city in Northwestern Gānsù Province. It was a major stop on the ancient Silk Road connecting straight to the Chinese plains leading to Cháng'ān (Xī’ān). which mentioned Chinese translationsSee Saeki, Yoshio (1937). The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China. Tokyo: Academy of Oriental Culture. of the Pentateuch (referred to as “牟世法王经”), including the Book of Genesis (“浑元经”), the Psalms (“多惠圣王经”), the Gospels (“阿思翟利容经”), Acts of Apostles (“传代经”), and a few others. The language in which these portions were translated was Middle Chinese.

Jesuit Shĕn FúzōngJesuit Shĕn Fúzōng 沈福宗 (?–1691), whose Latinized name was Michael Alphonsius, was a Qīng dynasty official from Nánjīng 南京. He converted to the Catholic faith and became one of a few Chinese who had traveled to Europe in the seventeenth century. Shĕn met with French King Louis XIV in 1684 and English King James II in 1685, and continued on to Lisbon, Portugal, where he entered the Society of Jesus. On his return to China, he died in Mozambique in 1691. This picture was painted by the German-English portrait painter Gottfried Kniller in 1685.During the Míng dynasty 明朝 (1378-1644), long after the disappearance of the Nestorian faith in China, Catholic missionaries came to China. Francis Xavier (1506-1552), a Basque Catholic, who was the companion of Ignatius of LoyolaThe Spanish nobleman and theologian, Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), was a leader of the Counter-Reformation and co-founder of the Society of Jesus, with Francis Xavier. and co-founder of the Society of Jesus, traveled as a pioneer to India, Japan, Borneo, and Maluku Islands to evangelize native populations. He died on the island of Shàngchuān 上川岛 in the South China Sea before reaching the Chinese Mainland.

Jesuit Shĕn FúzōngJesuit Shĕn Fúzōng 沈福宗 (?–1691), whose Latinized name was Michael Alphonsius, was a Qīng dynasty official from Nánjīng 南京. He converted to the Catholic faith and became one of a few Chinese who had traveled to Europe in the seventeenth century. Shĕn met with French King Louis XIV in 1684 and English King James II in 1685, and continued on to Lisbon, Portugal, where he entered the Society of Jesus. On his return to China, he died in Mozambique in 1691. This picture was painted by the German-English portrait painter Gottfried Kniller in 1685.During the Míng dynasty 明朝 (1378-1644), long after the disappearance of the Nestorian faith in China, Catholic missionaries came to China. Francis Xavier (1506-1552), a Basque Catholic, who was the companion of Ignatius of LoyolaThe Spanish nobleman and theologian, Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), was a leader of the Counter-Reformation and co-founder of the Society of Jesus, with Francis Xavier. and co-founder of the Society of Jesus, traveled as a pioneer to India, Japan, Borneo, and Maluku Islands to evangelize native populations. He died on the island of Shàngchuān 上川岛 in the South China Sea before reaching the Chinese Mainland.

The Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci 利玛窦 (1552–1610) led a group of Jesuits to China and introduced Western science, particularly mathematics and astronomy, to the imperial court. He initiatedDavid Mungello (2005) counted 920 European Jesuits who had participated in the China mission between 1552 (the year when Francis Xavier died) and 1800. According to Kenneth Latourette (1929), there were likely 240,000 Roman Catholics in China in 1844 and 720,490 in 1901. an inter-cultural dialogue with Chinese Confucian philosophers. Many Chinese intellectuals converted and became priests of the Society of Jesus. Matteo Ricci translated portions of the Bible into Chinese, mainly liturgical selections but not entire books. The only preserved translation is the Ten Commandments.

The Chinese Rites Controversy was a dispute in the seventeenth century among Catholic missionaries over the religious nature of Chinese customsChinese folk religion is diverse in origins, founders, local rites, and philosophical traditions. The most common rites practiced are Chinese shamanism 巫教 (manipulation of spirits) and Chinese exorcism 傩文化 (expulsion of spirits). and Confucian ritesConfucianism 儒家 is an ethical and humanist system developed by Confucius 孔子 (551–479 B.C.). Confucius emphasized family importance and formulated principles of ethical governance. Confucius viewed religious practices such as ancestor worship and sacrifice to spirits from a humanist standpoint, that is, religious rites aim to maintain social harmony. Throughout history, Confucianism was a belief system of Chinese elite, not of ordinary people. such as ancestor reverence or the principles of Tiān 天Tiān 天 is the concept of Heaven, of the Supreme God, and of the universe itself. and Qì 气Qì 气 means “air” and is the substance of life. This classical Chinese concept is reminiscent of the four basic elements in Ancient Greece: fire, air, water, and earth.. Tolerant Jesuits argued that these practices were secular in nature and compatible with the Christian faith, while other missionariesThe Dominicans and Franciscans started missionary work in China in the seventeenth century. Because these missionaries came from the Spanish colony of the Philippines where they adopted a policy of non-accommodation, they rejected the local customs and Jesuit practice in China. disagreed and contacted the Pope for guidance.

Kangxi Emperor

Kangxi Emperor

with a Jesuit astronomerBetween 1646 and 1720, the dispute embroiled Pope Clement XI (papacy 1700–1721), the Chinese Emperor Kāngxī 康熙帝 (1654–1722), scholars of European universities, and the Holy See’s Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the FaithThe congregation was founded by Pope Gregory XV in 1622, but after a name change, it is currently the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples..

Pope Clement XI issued the decree Cum Deus OptimusThe decree title in Latin means “With the Best God.” in 1704, in which he condemned the Confucian and Chinese folk rites. Specifically, the Pope

-

forbade the use of Tiān 天 “Heaven” and Shàngdì 上帝 “Lord Above,” but allowed the term Tiānzhǔ 天主 “Lord of Heaven” as names for God;

-

proscribed Christians from participating in Confucian rites; and

-

prohibited Christians from participating in rites of the Chinese folk religion such as ancestor worship or rites during which the soul of a deceased person is directed to the afterworld.

In 1715, Pope Clement XI further condemned the practice of Chinese religious rites in his papal bull Ex illa dieA papal bull is a sealed decree of the Pope. The meaning of the Latin title Ex illa die is “from that day.”. Chinese Emperor Kāngxī was vexed by the papal decree, changed his benevolent attitude toward Christianity, and banned Christian missionary activities in his imperial decree of 1721Li Dun Jen (1969, p. 224) translated the following from the Decree of Kāngxī: “Reading this proclamation, I have concluded that the Westerners are petty indeed. It is impossible to reason with them because they do not understand larger issues as we understand them in China. There is not a single Westerner versed in Chinese works, and their remarks are often incredible and ridiculous. To judge from this proclamation, their religion is no different from other small, bigoted sects of Buddhism or Taoism. I have never seen a document, which contains so much nonsense. From now on, Westerners should not be allowed to preach in China, to avoid further trouble.”. The Chinese Rites Controversy undermined the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Chinese government. Relationships have not been restored, even today.

The Běitáng Church 西什库北教堂The Běitáng Church in Běijīng was built by the Chinese Emperor Kangxi 康熙皇帝 in 1703.During the Chinese Rites Controversy, French missionary Jean Basset 巴设 (1662-1707) of the Paris Foreign Mission SocietyThe Missions Etrangères de Paris is a Roman Catholic missionary organization established in 1663 by instruction of the Holy See’s Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. The organization’s original purpose was to be independent of the Spanish and Portuguese colonial powers, and this organization remains active today, especially in East Asia. noted the lack of Bible translations into Chinese. Based in Sìchuān Province, he finally undertook the task together with Chinese scholar John Xu 许若翰. Before Father Basset died in 1707, he translated 80% of the Vulgate Version of the New Testament, but his work was never printed. Englishman Hodgman brought a copy of this translation to England in 1737, where it was deposited in the library of Sir Hans SloaneThis information is based on the article by Bernward Willeke (1945) titled “The Chinese Bible Manuscript in the British Museum” in Catholic Biblical Quarterly 7, pp. 450–453. and later in the British Museum. Protestant missionary Robert Morrison made a copy of this text, which he used for his translation of the Bible in 1823.

The Běitáng Church 西什库北教堂The Běitáng Church in Běijīng was built by the Chinese Emperor Kangxi 康熙皇帝 in 1703.During the Chinese Rites Controversy, French missionary Jean Basset 巴设 (1662-1707) of the Paris Foreign Mission SocietyThe Missions Etrangères de Paris is a Roman Catholic missionary organization established in 1663 by instruction of the Holy See’s Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. The organization’s original purpose was to be independent of the Spanish and Portuguese colonial powers, and this organization remains active today, especially in East Asia. noted the lack of Bible translations into Chinese. Based in Sìchuān Province, he finally undertook the task together with Chinese scholar John Xu 许若翰. Before Father Basset died in 1707, he translated 80% of the Vulgate Version of the New Testament, but his work was never printed. Englishman Hodgman brought a copy of this translation to England in 1737, where it was deposited in the library of Sir Hans SloaneThis information is based on the article by Bernward Willeke (1945) titled “The Chinese Bible Manuscript in the British Museum” in Catholic Biblical Quarterly 7, pp. 450–453. and later in the British Museum. Protestant missionary Robert Morrison made a copy of this text, which he used for his translation of the Bible in 1823.

After several private projects of Scripture translation by Catholics in the eighteenth century, Jesuit Louis de Poirot 贺请泰 (1735–1814) translated the New Testament and most of the Old Testament into Chinese. The manuscript was preserved for a long time in the Běitáng Church 北堂 Library in Běijīng, and is now held in Shànghǎi. The translation was based on the Vulgate. Basset and de Poirot’s translations are difficult to understand for modern Chinese speakers as the following excerpt of the Gospel of Luke illustrates.

Gospel of Luke 1: 13-19

| Basset’s Translation (1707) | De Poirot’s Translation (1814) | Chinese Union Translation (1919) | NIV English Translation (1979) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13 […] 尔妻依撒伯,将与尔生子,尔必名之若翰 […] | 13 […] 尔妻依撒伯尔要与你一子,尔宜取名若翰 […] | 13 […] 你的妻子伊利沙伯要给你生一个儿子,你要给他起名叫约翰 […] | 13 […] Your wife Elizabeth will bear you a son, and you are to call him John […] |

| 14 […] 且众以其生为乐矣。 | 14 […] 尔得此子,尔心乐多,人亦大喜。 | 14 […] 有许多人因他出世,也必喜乐。 | 14 […] and many will rejoice because of his birth, |

| 15 盖其为大主前,酒与麯皆不饮,犹在母腹,而满得圣风矣。 | 15 此子在主前本是大,他不宜饮酒及凡从菓压出的汁,自母腹即满被圣神。 | 15 他在主面前将要为大,淡酒浓酒都不喝,从母腹里就被圣灵充满了。 | 15 for he will be great in the sight of the Lord. He is never to take wine or other fermented drink, and he will be filled with the Holy Spirit even before he is born. |

| 16 且多化依腊尔子归于厥主神。 | 16 使多依斯拉耶耳嗣妇本主。 | 16 他要使许多以色列人回转,归于主他们的 神。 | 16 He will bring back many of the people of Israel to the Lord their God. |

| 18 […] 我妻亦暮年矣。 | 18 […] 妻年亦迈。 | 18 […] 我的妻子也年纪老迈了。 | 18 […] and my wife is well along in years. |

| 19 […] 我乃加别尔在神前者,使出语尔,报此福音。 | 19 […] 我是上主前的加彼厄尔,我奉命语尔,报尔此佳音。 | 19 […] 我是站在 神面前的加百列,奉差而来对你说话,将这好信息报给你。 | 19 […] I am Gabriel. I stand in the presence of God, and I have been sent to speak to you and to tell you this good news. |

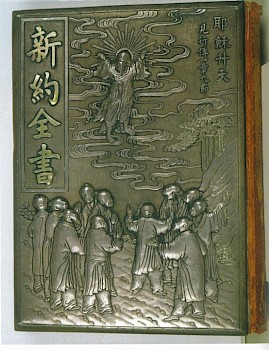

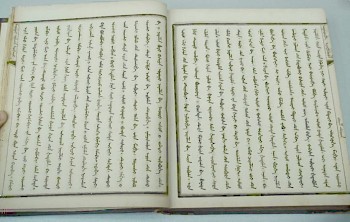

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries are the era of Protestant Scripture translation. The milestone in this process is the publication  Wényán New Testament, 1814This is one of four copies of the New Testament (1814) in Wényán 文言 that was presented to Emperor Pŭ Yí 溥仪. A Chinese official saved this copy during the political turmoil of 1911, and it was later given to the American Bible Society in 1944. See Noss, Phil (2007). A History of the Bible Translation. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura.of the Chinese Union Version in 1919, which is the authoritative and most prevalent Bible version of the twentieth century in China. This Bible is the endpoint of 100 years of rivalries, disappointments, and strugglesThe Term Question Controversy, which became the tangled part of the Chinese Rites Controversy mentioned earlier, was one important source of conflict. It developed in two stages. During the first stage between 1846 and 1855, Walter Henry Medhurst combed the Chinese Classics to define the meaning of Shén 神 and Shàngdì 上帝. According to Medhurst’s study, Shàngdì is perceived as the source of creation, the one without origin, while Shén is an emanation of Shàngdì that has to fulfill a function. He argued that the pair Shàngdì/Shén can render the dichotomy that exists in English between God/gods. James Legge supported this view by claiming that in ancient times, the Chinese believed in monotheism, which was then supplanted by polytheism. The terms Shàngdì and Shén are roughly representative of these two periods. William Boone dissented from this view. He emphasized that the Hebrew Elohim is a generic term, not a proper name, that must be rendered as such in other languages. For Boone, the generic term is Shén, not Shàngdì. No agreement was reached at this point. During the second stage of the Term Question Controversy, between 1863 and 1877, members of the Běijīng committee pushed for the use of the Catholic term Tiānzhŭ 天主 “Lord of Heaven,” which was met with resistance. The term was perceived as being merely definitional and too close to Catholicism. In the following years, the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) printed its Bibles with Shàngdì, while the American Bible Society used the term Shén or Tiānzhŭ. The controversy has not been resolved, but Chinese members of the Union Bible committees preferred the term Shén, which was used in the Union Bible of 1919 with a preceding blank case. and finally achieves a consensus between missionaries of different countries.

Wényán New Testament, 1814This is one of four copies of the New Testament (1814) in Wényán 文言 that was presented to Emperor Pŭ Yí 溥仪. A Chinese official saved this copy during the political turmoil of 1911, and it was later given to the American Bible Society in 1944. See Noss, Phil (2007). A History of the Bible Translation. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura.of the Chinese Union Version in 1919, which is the authoritative and most prevalent Bible version of the twentieth century in China. This Bible is the endpoint of 100 years of rivalries, disappointments, and strugglesThe Term Question Controversy, which became the tangled part of the Chinese Rites Controversy mentioned earlier, was one important source of conflict. It developed in two stages. During the first stage between 1846 and 1855, Walter Henry Medhurst combed the Chinese Classics to define the meaning of Shén 神 and Shàngdì 上帝. According to Medhurst’s study, Shàngdì is perceived as the source of creation, the one without origin, while Shén is an emanation of Shàngdì that has to fulfill a function. He argued that the pair Shàngdì/Shén can render the dichotomy that exists in English between God/gods. James Legge supported this view by claiming that in ancient times, the Chinese believed in monotheism, which was then supplanted by polytheism. The terms Shàngdì and Shén are roughly representative of these two periods. William Boone dissented from this view. He emphasized that the Hebrew Elohim is a generic term, not a proper name, that must be rendered as such in other languages. For Boone, the generic term is Shén, not Shàngdì. No agreement was reached at this point. During the second stage of the Term Question Controversy, between 1863 and 1877, members of the Běijīng committee pushed for the use of the Catholic term Tiānzhŭ 天主 “Lord of Heaven,” which was met with resistance. The term was perceived as being merely definitional and too close to Catholicism. In the following years, the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) printed its Bibles with Shàngdì, while the American Bible Society used the term Shén or Tiānzhŭ. The controversy has not been resolved, but Chinese members of the Union Bible committees preferred the term Shén, which was used in the Union Bible of 1919 with a preceding blank case. and finally achieves a consensus between missionaries of different countries.

The struggle for an authoritative Chinese Bible was shaped by the struggle for a lingua franca that could unify the whole country, which was intense at the turn of the twentieth century. Since the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907), there were two literary standards, Wényán 文言The nineteenth century missionaries called Wényán 文言 “High Wénlǐ” 深文理, but it is not a standard name used in China., the classical literary language, and Báihuà 白話The nineteenth century missionaries called Báihuà 白話 “Easy Wénlǐ” 易文理, but it is not a standard name used in China., the vernacular standard of ordinary people.

Wényán 文言 enjoyed great prestige among the population in the early twentieth century and was accorded the status of the language of the learned. The vast majority of Chinese literature, history, philosophy, and other sciences were written in Wényán 文言, the only truly national form of Chinese. Like Latin, Wényán 文言 and Báihuà 白話 are written languages that cannot be spoken. They are different from any current Chinese dialect and thus cannot assume the role of a lingua franca.

In 1913, a language commission was established in Beijing with representatives from all over China. A controversy erupted over which dialect should be selected as China’s lingua franca. Finally, the northern representatives forced their point, resulting in the Beijing dialect being chosen as the Standard Language.

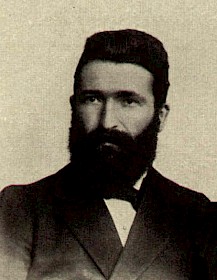

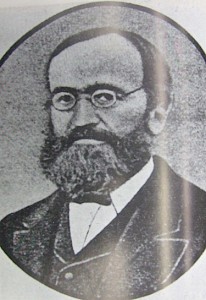

Joseph Schereschewsky

Joseph Schereschewsky

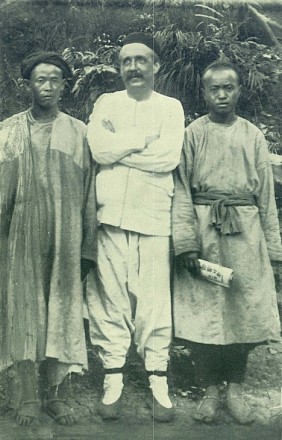

施约瑟 (1831-1906)Samuel Isaac Joseph Schereschewsky 施约瑟 (1831–1906) was a Lithuanian Jew, who studied in Germany, emigrated to the United States, converted to the Christian faith, studied theology at the General Theological Seminary of the Episcopal Church in New York, and volunteered as a missionary. He was sent to China by the American Episcopal Mission, which belonged to the network of Anglican missions, and arrived in Shànghăi in 1859. He founded St. John’s College and was ordained as the Anglican Bishop of Shànghăi in 1877. He was a member of the translation committee for the Standard Běijīng language, and he translated most of the Old Testament. He was a Bible translator extraordinaire whose work influenced the Chinese Union Version of 1919. Translators of the

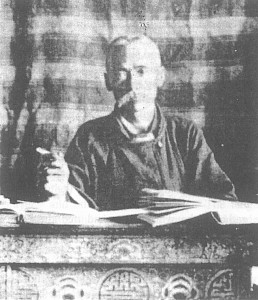

Translators of the

Chinese Union Version in 1906The photo appeared in “China and the Gospel,” Annual Report of the China Inland Mission, 1906. In the nineteenth century, five different complete translations of the Bible into Wényán 文言 were completed, with the first two under intense governmental persecution:

-

1822: by Joshua Marshman 马士曼Joshua Marshman 马士曼 (1768-1837) was a colleague of Willian Carey and was based at the Baptist Serampore Mission in Calcutta, India. Marshman and Carey coordinated Bible translation into several Indian languages. With the assistance of Johannes Lassar, he published the Chinese Bible incrementally in Serampore. and Johannes Lassar 拉撒尔Johannes Lassar 拉撒尔 was an Armenian born in Macao. He prepared a first draft of the New Testament in 1816 based on the Greek text and the English King James Version. He and Marshman used the term Shén 神 “God,” Shèng Fēng 圣风 “Holy Spirit,” and zhàn 蘸 “baptize.” (Baptist Missionaries);

-

1823: by Robert Morrison 马礼逊Robert Morrison 马礼逊 (1782–1834) was sent by the London Missionary Society 伦敦传道会 to China, and he arrived in Macao in 1807. Under intense governmental persecution, he completed a translation of the Bible in 1823. He returned to the United Kingdom on a furlough in 1824, where he was made a fellow of the Royal Society for his work on a Chinese-English dictionary. He was also awarded the title of Doctor of Divinity by the University of Glasgow. The keywords Morrison used in his translation of the Bible were the terms Shén 神 “God,” Shèng Fēng 圣风 “Holy Spirit,” and xĭ 洗 “baptize.” and William Milne 米憐William Milne 米憐 (1785–1822) was the second missionary of the London Missionary Society who was sent to China. He arrived in Macao in 1823 and was the only assistant of Robert Morrison. He baptized Chinese evangelist Liáng Fā 梁发, who later preached the gospel to the Chinese rebel leader Hóng Xiùquán 洪秀全. In 1815, Milne moved to the Malayan Straits Settlement of Malacca (present-day Malaysia), where he continued to serve Chinese immigrants. Collaborating with Robert Morrison on the translation of the Chinese Bible, he contributed by translating the books of Deuteronomy through Job. (London Missionary Society);

-

1847: by W. H. Medhurst 麦都思Walter Henry Medhurst 麦都思 (1796–1857) was a missionary of the London Missionary Society. He was sent to Malacca in 1816, where he learned Malay and Chinese. In 1842, he moved to Shànghăi and collaborated with Karl Gützlaff and Elijah Bridgman on the translation of the Bible in Classical Chinese, which was completed in 1847. He was an influential discussant in the Term Question Controversy; he had combed Chinese Classics for different names for God., K. Gützlaff 郭士立Karl Gützlaff 郭士立 (1803–1851) was a German missionary who went to Singapore and Bangkok, where he translated the Gospel of Luke in Thai in 1834. He then moved to Macao and Hong Kong, made short trips to Japan, and successfully translated the Gospel and Epistles of John in Japanese in 1837. After 1840, he started working on a Chinese Bible translation in cooperation with William Henry Medhurst and Elijah Bridgman. He contributed by translating most of the Old Testament. The entire Bible was completed in 1847. Due to the government’s interdiction of foreign missionary activities in Inner China, he started a school of “native missionaries.” In 1851, he discovered the fraud of the “missionaries” whom he had engaged: these “missionaries” reported activities at places to where they had never traveled. Shortly afterwards, he died. As a prolific writer, he inspired numerous people in Europe. A street in Hong Kong is named after him., and E. Bridgman 裨治文The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions appointed Elijah Coleman Bridgman 裨治文 (1801–1861) as its first missionary for service in China, and he arrived in Guăngzhōu in 1830. He contributed to the translation of the Bible in Classical Chinese and was active in Christian education. He later moved to Shànghăi, where he died and was buried with his wife., whose translation was adopted by Hóng Xiùquán 洪秀全Hóng Xiùquán 洪秀全 (1814–1864) was a Chinese Hakka rebel leader who led an insurrection against the Manchu Government (Spence 1996). When he failed the provincial examinations on four occasions, he saw visions of a fatherly and of a brotherly figure. After a Christian missionary provided him with summaries of the Bible, he interpreted the fatherly figure as God the Father, the brotherly figure as Jesus Christ, and proclaimed himself the younger brother of Jesus Christ. During the 1840s, he received further instructions by Christian missionaries and adopted the translation of Medhurst, Gützlaff, and Bridgman as the doctrinal base of his emerging organization of believers. In 1851, Hóng Xiùquán gathered 30,000 followers and tensions with the Manchu government arose. He rebelled when the government troops tried to disperse his followers. Hóng defeated the government troops, occupied Nánjīng in 1853, and established a kind of theocracy, the Heavenly Kingdom or Tàipíngtiānguó 太平天囯. His rule was terminated in 1864 when government forces overcame the rebel’s defense lines, and Hóng Xiùquán was killed in 1864. He continued to inspire the Miao rebel movement in Guìzhōu., the leader of the Tàipíngtiānguó 太平天囯 movement;

-

1854: the Delegates’ VersionIn 1843, 12 missionaries representing various missionary organizations decided to revise the Bible. They established committees in the five ports determined in the Treaty of Nánjīng of 1842: Shànghǎi 上海, Guăngzhōu 广州, Níngbō 宁波, Fúzhōu 福州, and Xiàmén 厦门. Each committee sent a delegate (hence the name Delegates' Version) to a central committee that made final decisions on different issues. by W. H. Medhurst 麦都思, W. J. Boone 文惠廉William Jones Boone 文惠廉 (1811–1864) was a missionary of the American Episcopal Mission, who arrived in Macao 1839 and relocated to Shànghăi in 1844, where he served as an Anglican Bishop until his death. He was on the committee of the Delegates’ Version and played an influential role in the “Term Question” controversy. He argued for the use of Shén 神 for God., W. M. LowrieWalter Macon Lowrie 娄理华 (1819–1847) was a missionary appointed by the American Presbyterian Mission. He arrived in China in 1842., J. StronachJohn Stronach 施敦力 (1810–1888) was a British missionary of the London Missionary Society. He was stationed in Xiàmén 厦门 and was the representative of the Xiàmén committee on the Delegates’ Version committee., and E. C. Bridgman 裨治文; and

-

1863: by E. C. Brigdman 裨治文 and M. S. Culbertson 克陛存Michael Simpson Culbertson 克陛存 (1819–1862) was a missionary of the American Presbyterian Mission. He was stationed in Níngbō from 1845 to 1851 and later in Shànghǎi from 1851 to 1862. after they separated from the Delegates’ Committee.

In the 1880s, the Protestant churches were disappointed in the lack of an authoritative translation and convened a General Mission ConferenceSee Zetzsche, Jost (1999). “The Work of Lifetimes: Why the Union Version Took Nearly Three Decades to Complete.” In Bible in Modern China: The Literary and Intellectual Impact, edited by Irener Eber, Sze-Kar Wan, and Knut Walf, 77–100. Sankt Augustin: Institut Monumenta Serica. in 1890 to prepare a new translation in Wényán 文言, Báihuà 白話, and Vernacular Mandarin Chinese, the speech of Beijing. Three translation committees were formed.

As it became increasingly clear that Mandarin would become the lingua franca, the classical language committees were dissolved by 1907, and the Mandarin translation was published in 1919 under the name Chinese Union Version. It remains the authoritative Chinese Bible version but was revised once in 2010 by the Hong Kong Bible Society.

Besides the Classical languages and Mandarin Chinese, missionaries also translated the Bible into other Chinese dialects. The European and Chinese definitions of “language” 语言 and “dialect” 方言 differ throughout history. In the European understanding, two speeches are dialects if they are intelligible; they are languages if not. The Chinese use ethnic and political traits to correlate two speeches. Two speeches are dialects if the people who use them share the same ethnic group or nationality; they are two languages if they belong to different groups.

Speakers of the Chinese dialects are the ethnic Hàn 汉, but the linguistic variation between these dialects is comparable to or even more significant than that of the Germanic or Romance languages. There are nine Chinese dialect groups, and each has a complex subsystem.

Speakers of the Chinese dialects are the ethnic Hàn 汉, but the linguistic variation between these dialects is comparable to or even more significant than that of the Germanic or Romance languages. There are nine Chinese dialect groups, and each has a complex subsystem.

|

Dialect Group |

Population |

|---|---|

|

Mandarin 官 |

960 Million |

|

Jìn 晋 |

48 Million |

|

Gàn 赣 |

31 Million |

|

Mǐn 闽 |

70 Million |

|

Yuè 粤 |

60 Million |

|

Píng平 |

3.8 Million |

|

Hakka 客家 |

30 Million |

|

Xiāng 湘 |

38 Million |

|

Wú 吴 |

80 Million |

|

Huī 徽 |

4.6 Million |

Table 3: The Chinese Dialects

Translations of the Bible in Chinese dialects emerged shortly after the completion of the first Bibles in Wényán 文言. Bibles in Mandarin were published in 1874, in four different Mǐn 闽 dialects in 1884–1922, in Cantonese in 1894, in four different Wú 吴 dialects in 1901–1914, and in Hakka in 1916. Portions of the Bible were translated in 25 different Chinese dialects. Details are displayed in the following chart.

|

ISO639-3 |

Dialect |

Chinese Dialect Group |

BookThe first translation of one of the sixty-six books of the Bible. | NTThe first translation of the New Testament. | BibleThe first translation of the entire Bible. |

|

ltc |

Middle Chinese |

Root |

650 (?)A stela was found in Xī’ān in 1625 commemorating Christian activities in China during the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618–907). The stela was erected in A.D. 781, after the Nestorian missionaries had evangelized the local population for some time. The text on the stela includes the mention “Scriptures were translated,” which refers to the translation of some portion of the Bible, although no text has been preserved. In 1907, Christian documents were found in the Mògāo Caves 莫高窟 in Dúnhuāng 敦煌 that mentioned Chinese translations of the Pentateuch (referred to as “牟世法王经”), including the Book of Genesis (“浑元经”), translation of the Psalms (“多惠圣王经”), the Gospels (“阿思翟利容经”), Acts of Apostles (“传代经”), and a few others. The language in which these portions were translated was Middle Chinese. |

|

|

|

lzh |

High Wénlǐ 深文理This term, coined by missionaries, designates the Classical Chinese language spoken during B.C. 500-A.D. 200. |

Literary 文言文 |

1810The first complete book of the Bible was the Gospel of Matthew, which was translated by Joshua Marshman and Johannes Lassar in Serampore, India, in 1810. It was based on the Greek text and the English King James Version. Within the same year, Robert Morrison, who was assisted by William Milne, published the Acts of the Apostles in Guăngzhōu 广州. Morrison’s translation relied on the Greek text, Jean Basset’s 1707 translation, and the English King James Version. | 1814The New Testament was first completed by Robert Morrison and William Milne in 1814. However, Joshua Marshman and Johannes Lassar completed another version of the New Testament in 1816. | 1822Joshua Marshman and Joannes Lassar completed and published the entire Bible in Serampore in 1822. Robert Morrison, with the support of William Milne, translated another version of the entire Bible in 1819 but published it in Guăngzhōu 广州 in 1823. The Delegates’ Version was completed in 1855 by W. H. Medhurst (London Missionary Society), W. J. Boone (American Episcopal Mission), W. M. Lowrie (American Presbyterian Mission), J. Strotrach (London Missionary Society), and E. C. Bridgman (American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions). |

|

lzh |

Easy Wénlǐ 易文理Easy Wénlǐ 易文理 is also a term created by missionaries and corresponds to simplified Classical Chinese, in which the literary balance and richly embroidered figures of speech are abandoned in favor of a more direct communication of ideas. Easy Wénlǐ 易文 and High Wénlǐ 深文理 were superseded by Mandarin Chinese after 1919. |

Literary 文言文 |

1883The Gospels of Mark and John were first translated in 1883 by Griffith John (London Missionary Society). | 1885The New Testament was first completed in 1885 by Griffith John (London Missionary Society). | 1902The entire Bible was completed in 1902 by S. I. J. Schereschewsky (American Episcopal Mission) and others from the Easy Wénlǐ Union Bible Committee, and it was published in the same year by the American Bible Society in Shànghăi. |

|

cmn |

Standard 普通话 |

Guān 官, Běijīng 北京 |

1864In Standard Chinese, the Gospel of John was first translated in 1864 by the Beijing Committee, which included William A. P. Martin (American Presbyterian Mission), Joseph Edkim, (London Missionary Society), S. I. J. Schereschewsky (American Episcopal Mission), J. S. Burdon (Church Missionary Society), and H. Blodget (American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions). The Beijing Committee was appointed in 1861. | 1872The New Testament was first translated in 1872 by the Beijing Committee. | 1874The Old Testament was completed in 1874 by S. I. J. Schereschewsky. His Old Testament version and the Beijing Committee’s New Testament version became the standard Mandarin Bible until the publication of the Union Version. In 1919, the Union Bible Committee, which included J. Edkins, J. Wherry, D. Z. Sheffield, T. W. Pearce, and L. Lloyd, completed an authoritative Bible translation, which is still in use today. The Chinese Union Version was published in 1919 by the American Bible Society in Shànghăi. The first integral Catholic translation of the Bible was completed in 1953 by a team led by Italian Father Gabriele M. Allegra (1907–1976) in Hong Kong. |

|

cmn |

Nánjīng 南京 |

Guān 官, Jiānghuái 江淮 |

1854The Gospel of Matthew was translated in 1854 from the Delegates’ Wénlǐ Version by a Chinese, under the supervision of W. H. Medhurst and J. Stronach (both from the London Missionary Society). | 1857The New Testament was completed under the same circumstance in 1857. It was published in the same year by the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) in Shànghăi. |

|

|

cmn |

Yāntái 烟台Kiaotung is an older name for this Guān dialect spoken in Yāntái 烟台, a city in Shāndōng Province. |

Guān 官, Jiāoliáo 胶辽 |

1918The Gospel of Mark was translated in 1918 by missionaries of the North China Baptist Mission, a branch of the American Southern Baptist Mission. |

|

|

|

cmn |

Jǐnán 济南 |

Guān 官, Jìlǔ 冀鲁 |

1892The Gospels of Luke and John were translated in 1892 by C. H. Judd and E. Tomalill (China Inland Mission). |

|

|

|

cmn |

Wǔhàn 武汉The city is formerly known as Hànkǒu 汉口 from which modern-day Wǔhàn 武汉 evolved. |

Guān 官, Xīnán 西南 |

1921The Gospel of Mark was first translated in 1921 by J. H. L. Patterson (London Missionary Society). |

|

|

|

hak |

Méizhōu 梅州The Hakka language in Meixian 梅县 (literally “Plum County”), a district in Méizhōu 梅州 Prefecture, Northeastern Guǎngdōng Province, is the standard dialect of Hakka. |

Hakka 客家 |

1860The Gospel of Matthew was first translated in 1860 by missionaries of the Basel Missionary Society, including R. Lechler, P. Wilmes, C. P. Piton, and Kong Fatlin, an ordained Chinese pastor. It was published in Berlin in the same year. | 1883The first New Testament was completed in 1883 by missionaries of the Basel Missionary Society, including the same individuals who completed the Gospel of Matthew. The version using the Roman script was published in Basel in 1883 by the BFBS, while the version using Chinese characters was published in Guăngzhōu in the same year by the BFBS. | 1916The first entire Bible in Chinese characters was completed in 1916 by A. Nagle, G. A. Guzman, and W. Ebert (all from the Basel Missionary Society) and was published in Shànghăi in the same year by the BFBS. The Bible was retranslated between 1984 and 2012 and published by the Bible Society in Taiwan in Taibei in 2012, in both Romanized Hakka and Chinese characters. |

|

hak |

Hépó 河婆Wukingfu 五经富 is a town in Hépó 河婆, which is a subdistrict of Jiēxī 揭西 County in Guangdong Province. The English Presbyterian Mission established a mission there in 1871. |

Hakka 客家 |

|

1916The first New Testament was translated by a committee of the English Presbyterian Mission, including M.C. Mackenzie and Phang Ki Fung. |

|

|

hak |

Lóngyán 龙岩A former name of this Hakka dialect was the Tīngzhōu 汀州 dialect. |

Hakka 客家 |

1919The Gospel of Matthew was translated in 1919 by C. R. Hughes and E. R. Rainey (London Missionary Society). |

|

|

|

cdo |

Fúzhōu 福州 |

Mǐn 闽, Eastern 东 |

1852The Gospel of Matthew was first translated into the Fúzhōu 福州 subdialect of Eastern Mǐn in 1852 by Moses Clark White 怀德 (American Methodist Episcopal Mission) and published in Fúzhōu by the American Bible Society in the same year. | 1856The New Testament was first completed in 1856 by William Welton 温敦 (Church Missionary Society) and Lyman Birt Peet 弼利民 (American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions), and it was published by the American Bible Society in Fúzhōu in the same year. | 1891The Old Testament was completed by a committee, which included Caleb Cook Baldwin 摩嘉立, James Walker (both with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions), John Richard Wolfe 胡約翰, Llwellyn Lloyd, William Banister (all with the Church Missionary Society), and Nathan Plumb (American Methodist Episcopal Mission), in 1888. A revised version of the Old Testament and the New Testament was jointly published as the first complete Bible by the American Bible Society and BFBS in 1891. |

|

mnp |

Shàowǔ 邵武 |

Mǐn 闽, Northern 北 |

1891The Epistle of James was translated in 1891 by J. E. Walker (American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions). |

|

|

|

mnp |

Jiàn'ōu 建瓯 |

Mǐn 闽, Northern 北 |

|

1896The first New Testament was translated and revised in 1896 by L. J. Bryer (Church of England Zenana Missionary Society). |

|

|

mnp |

Jiànyáng 建阳 |

Mǐn 闽, Northern 北 |

1898The Gospel of Mark was first translated in 1898 by Mr. and Mrs. H. S. Phillips (Church Missionary Society). |

|

|

|

cpx |

Púxiān 莆仙The older name for the Púxiān Mǐn 莆仙闽 dialect is Hinghua Mǐn 兴化话 spoken in Pútián 莆田 County. |

Mǐn 闽, Púxiān 莆仙 |

1892William Nesbitt Brewster 蒲魯士 (American Methodist Episcopal Mission) translated the Gospel of John into Púxiān Mǐn in 1892. | 1902Aided by native speakers, W. N. Brewster 蒲魯士 (American Methodist Episcopal Mission) completed the first New Testament in Púxiān Mǐn in 1902. | 1912W. N. Brewster 蒲魯士 (American Methodist Episcopal Mission) completed the first entire Bible in 1912. It was published in the same year by the American Bible Society. |

|

nan |

Teochew 潮汕 |

Mǐn 闽, Southern 南 |

1875The Book of Ruth was translated in 1875 by S. B. Partridge (American Baptist Missionary Union). | 1896The New Testament was completed in 1896 by missionaries including S. B. Partridge, W. Ashmore, and A.M. Fields (American Baptist Missionary Union). | 1922The entire Bible was completed in 1922 by English Presbyterian Missionaries, including W. Duffus, George Smith, J. C. Gibson, and H. L. Mackenzie. |

|

nan |

Hainanese 海南 |

Mǐn 闽, Southern 南 |

1891In 1891, C. C. Jeremiassen (American Presbyterian Mission) translated the Gospel of Matthew with the help of F. P. Gilman. |

|

|

|

nan |

Hokkien 福建Hokkien has three subdialects: the Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, and Xiamen (Amoy) dialects, which are all spoken in Fujian Province and Taiwan. The Bible was translated into the Xiamen (Amoy) dialect. |

Mǐn 闽, Southern 南 |

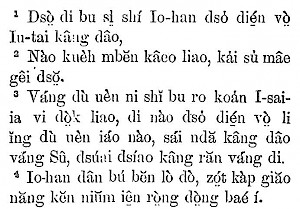

1852The Gospel of John was first translated in 1852 by Elihu Doty (Dutch Reformed Mission) and published in the same year by the BFBS in Guăngzhōu. | 1873The New Testament was translated into the Amoy dialect by the first missionary to Taiwan, James Laidlaw Maxwell 马雅各 (English Presbyterian Church) in 1873, by using the Pe̍h-ōe-jī orthography. | 1884The Old Testament was completed in the Amoy dialect by James Laidlaw Maxwell 马雅各 (English Presbyterian Church) in 1884, by using the Pe̍h-ōe-jī orthography. In 1930, Thomas Barclay 巴克礼 (English Presbyterian Church) retranslated the New Testament in 1916 and the entire Bible, using the Romanized Pe̍h-ōe-jī orthography. The Amoy Romanized Bible was published in 1933. It was later transliterated in Chinese characters and published in 1996. |

|

wuu |

Wēnzhōu 温州 |

Wú 吴, Ōujiāng 瓯江 |

1892W. E. Soothill (United Methodist Free Church) translated and revised the Gospel of Matthew in 1892. | 1902W. E. Soothill (United Methodist Free Church) translated the entire New Testament in 1902. The manuscript was published in the same year by the BFBS. |

|

|

wuu |

Shànghǎi 上海 |

Wú 吴, Tàihú 太湖 |

1847Walter Henry Medhurst 麦都思 (London Missionary Society) translated the Gospel of John in 1847 and privately published it in Shànghăi in the same year. | 1870The New Testament was completed in 1870 by John Marshall Willoughby Farnham 法納姆 (American Presbyterian Mission) and published in Roman characters by the American Bible Society in Shànghăi in the same year. | 1908The entire Bible was completed in 1913 by the Shànghăi Bible Committee and published by the American Bible Society in Shànghăi. |

|

wuu |

Níngbō 宁波 |

Wú 吴, Tàihú 太湖 |

1852The Gospel of Luke was translated in 1852 by missionaries in Níngbō, including W. A. Russell (Church Missionary Society), D. B. McCartee, W. A. P. Martin, and H. V. V. Rankin (American Presbyterian Mission). | 1868The New Testament was completed in 1868 by J. H. Taylor (China Inland Mission), F. F. Gough, and G. E. Moule (Church Missionary Society). A revised edition was published in 1874 by the American Bible Union in Shànghăi. | 1901The entire Bible was completed in 1901 by R. Goddard (American Baptist Missionary Union), W. S. Moule (American Presbyterian Mission), and N. B. Smith (Church Missionary Society). It was published in the same year by the BFBS in Shànghăi. |

|

wuu |

Hángzhōu 杭州 |

Wú 吴, Tàihú 太湖 |

1879The Gospel of John was first translated in 1879 by G. E. Moule (Church Missionary Society) with reference to the Beijing Mandarin version. |

|

|

|

wuu |

Sūzhōu 苏州 |

Wú 吴, Tàihú 太湖 |

1879The Gospels and Acts of Apostles were translated in 1879 by John W. Davis (American Presbyterian Mission) and published in the same year by the Shànghăi American-Chinese Book Company. | 1881The New Testament that was adapted from the Shànghăi Version by G. F. Fitch (American Presbyterian Mission) and A. P. Parker (American Southern Methodist Episcopal Mission) was completed in 1881. | 1908The entire Bible was adapted and retranslated in 1908 by J. W. Davis, D. M. Lyon, J. H. Hayes (American Presbyterian Mission), and T. C. Britton (American Southern Baptist Mission). |

|

wuu |

Tāizhōu 台州 |

Wú 吴, Tāizhōu 台州 |

1880The Gospels were translated in 1880 by W. D. Rudland (China Inland Mission), assisted by his missionary colleagues, including C. Thomson, C. H. Jose, and J. G. Kauderer. | 1881The New Testament was translated in 1881 by W. D. Rudland and his missionary colleagues: C. Thomson, C. H. Jose, and J. G. Kauderer (all with the China Inland Mission). | 1914The entire Bible was completed in 1914 by W. D. Rudland (China Inland Mission) and his colleagues. |

|

wuu |

Jīnhuá 金华 |

Wú 吴, Wùzhōu 务州 |

1866The Gospel of John was translated in 1866 by H. Jenkins (American Baptist Missionary Union) and published in the same year by the American Bible Society in Shànghăi. |

|

|

|

yue |

Liánzhōu 连州 |

Yuè 粤, Luōguǎng 罗广 |

1904The Gospel of Matthew was translated by Eleanor Chestnut 车以纶, a medical missionary of the American Presbyterian Mission in Liánzhōu in 1905. The manuscript was published by the American Bible Society in 1905. In the same year, Eleanor Chestnut was killed by villagers in Liánzhōu. |

|

|

|

yue |

Cantonese 广东话 |

Yuè 粤, Yuè-Hǎi 粤海 |

1862Charles Finney Preston 丕思业 (American Presbyterian Mission) translated the Gospels of Matthew and John into Cantonese 广东话 by 1862. The Gospels were published by the American Bible Society in Guăngzhōu in the same year. | 1877George Piercy 俾士 of the English Wesleyan Mission completed the New Testament in 1877, and it was privately printed in Guăngzhōu in the same year. | 1894The entire Bible in Cantonese was completed in 1894 by a committee of the American Presbyterian Mission, including Benjamin Couch Henry 香便文 and Henry Moyes 那夏礼. The manuscript was published by the American Bible Society. |

Table 4: Bible Translation in Chinese Dialects

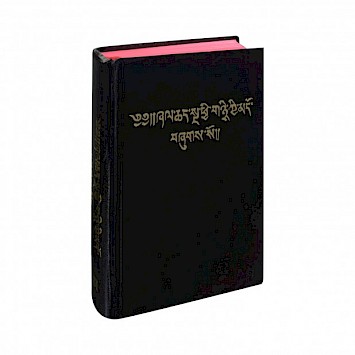

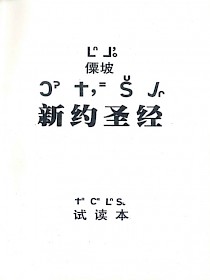

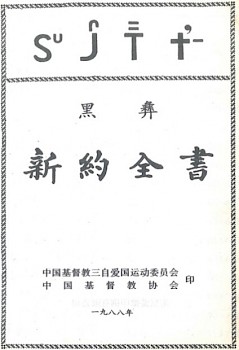

Cover of Hakka Bible,

Cover of Hakka Bible,

reprint of 1923The only Bible translations that are still used today are the Mandarin, Hokkien, and Hakka translations. Since 1949, Mandarin Chinese has gradually risen to such prominence that virtually all Hàn Chinese acquired native competence of the lingua franca.

Churches have adapted to this situation by shifting usage to the Mandarin Chinese Bible (the Chinese Union Version) in the twentieth century. The Scriptures are either entirely read in Mandarin Chinese or instantly translated into the respective dialect from the Mandarin Bible.

Since the nineteenth century, sizable Hokkien and Hakka populations migrated to other countries in Southeast Asia and North America. Hokkien (Taiwanese) is also spoken by 70% of the population in Taiwan. These Hokkien and Hakka diaspora communities continued using the Bibles of 1884 and 1916. Under the authority of the Bible Society of Taiwan, the Bibles were revised or retranslated to adapt to language use in the twenty-first century: in 2008, for Hokkien and in 2012, for Hakka.

Chinese Jews and Muslims (1)

The earliest specific evidenceScholars do not consider the mention of Sinim in Isaiah 49:12 to refer to the Chinese, nor do they accept the theory that Noah and his three sons, Shem, Ham, and Japhet, reached China, as Muslim sources from the A.D. tenth century had suggested. Scholars also disregard claims that the Chinese classics of the first millenary B.C. such as the Yìjīng 易经 or Laozi’s Dàodéjīng 道德经 are connected to the Hebrew Torah. No linkage between the Hebrew and Chinese language or script is believed to exist. Finally, scholars also reject the idea that the Chinese are linked to the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel (see Leslie 1998). of the presence of Jews in China comes from the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618–907). An eighth century manuscript in Hebrew script was found in the Mògāo Caves 莫高窟 in Dúnhuāng 敦煌, a station on the ancient Silk Road.

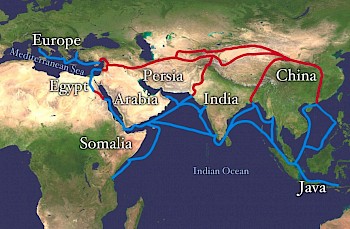

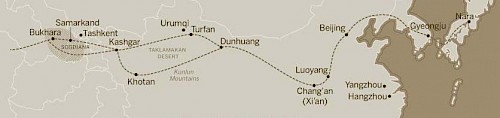

Ancient Silk Roads by Land and by SeaBC 206 – AD 1450.According to Arabic sources, Jews were among the many foreigners killed in the agitation of Khânfû (Canton 广州) in 878. The Jewish community at Kāifēng 开封 in Henan Province was founded during the Song dynasty (960–1279); their synagogue (qīngzhēnsì 清真寺) was built in 1163.

Ancient Silk Roads by Land and by SeaBC 206 – AD 1450.According to Arabic sources, Jews were among the many foreigners killed in the agitation of Khânfû (Canton 广州) in 878. The Jewish community at Kāifēng 开封 in Henan Province was founded during the Song dynasty (960–1279); their synagogue (qīngzhēnsì 清真寺) was built in 1163.

Chinese people referred to the Jewish religion as tiăojīnjiào 挑筋教, literally “the religion which removes the sinew,” which likely refers to the Jewish prohibition of eating the tendon attached to the socket of the hip (see Genesis 32:32).

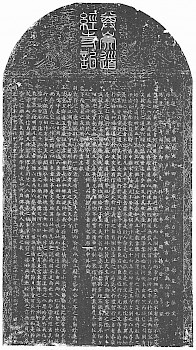

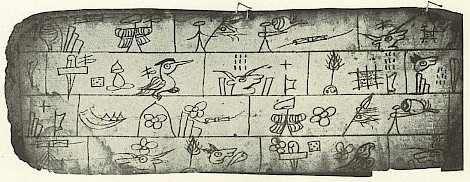

Stela of 1512Reproduced as Ink Rubbing.The Jew Moshe ben Abram (1619–1657), whose Chinese name was Zhào Yìngchéng 赵映乘, became a special envoy of the emperor at the end of the Míng dynasty 明朝 (1368–1644). He helped rebuild the Kāifēng synagogue that was destroyed in a flood in 1642. The Jewish community practiced the Rabbinic prayers and festivals. They copied 13 Torah scrolls in Hebrew. There is no information available on Jewish efforts to translate portions of the Torah into Chinese.

Stela of 1512Reproduced as Ink Rubbing.The Jew Moshe ben Abram (1619–1657), whose Chinese name was Zhào Yìngchéng 赵映乘, became a special envoy of the emperor at the end of the Míng dynasty 明朝 (1368–1644). He helped rebuild the Kāifēng synagogue that was destroyed in a flood in 1642. The Jewish community practiced the Rabbinic prayers and festivals. They copied 13 Torah scrolls in Hebrew. There is no information available on Jewish efforts to translate portions of the Torah into Chinese.

Four stelae in Chinese that are dated 1489, 1512, 1663, and 1679 were inscribed with information about the religion, festivals, and the history of the community. At its height, the Jewish community in Kāifēng had more than 5,000 members.

Kāifēng JewsAt the turn of the twentieth century.A number of setbacks occurred after the sixteenth century, which contributed to the decline of the Kāifēng Jewish community and of other Jewish communities in China, such as floods, calamities, and the turmoil caused by the Heavenly Kingdom 太平天国 rebellion in the nineteenth century. In 1850, the Kāifēng synagogue was reported to be in poor shape. By 1866, the synagogue had been dismantled, and no synagogue was rebuilt afterwards. Donald Leslie, the author of Jews and Judaism in traditional China, reasoned that the decline is mainly due to the lengthy isolation from other Jewish communities in the world. In the twentieth century, the Chinese government classified the Kāifēng Jews within the Hàn nationality. The Kāifēng Jews are reported to use seven Chinese surnames, among which are Lĭ 李 and Gāo 高. These surnames supposedly represent the names of Levi and Cohen.

Kāifēng JewsAt the turn of the twentieth century.A number of setbacks occurred after the sixteenth century, which contributed to the decline of the Kāifēng Jewish community and of other Jewish communities in China, such as floods, calamities, and the turmoil caused by the Heavenly Kingdom 太平天国 rebellion in the nineteenth century. In 1850, the Kāifēng synagogue was reported to be in poor shape. By 1866, the synagogue had been dismantled, and no synagogue was rebuilt afterwards. Donald Leslie, the author of Jews and Judaism in traditional China, reasoned that the decline is mainly due to the lengthy isolation from other Jewish communities in the world. In the twentieth century, the Chinese government classified the Kāifēng Jews within the Hàn nationality. The Kāifēng Jews are reported to use seven Chinese surnames, among which are Lĭ 李 and Gāo 高. These surnames supposedly represent the names of Levi and Cohen.

The Chinese Government defines the Huí 回 nationality, without regard to religion, as the descendants of Arab and Central Asian people who had settled in China during the Tang (AD 618–907) and Song (AD 960–1279) dynasties.

Huí family in Níngxià ProvinceThe Huí ancestors mainly originated from places along the ancient Silk Road. The overwhelming majority of the 10.5 million Huí people are Muslims. Huí communities exist across the country, but are concentrated in Northwestern China (Níngxià, Gānsù, Qīnghăi, and Xīnjiāng provinces).

Huí family in Níngxià ProvinceThe Huí ancestors mainly originated from places along the ancient Silk Road. The overwhelming majority of the 10.5 million Huí people are Muslims. Huí communities exist across the country, but are concentrated in Northwestern China (Níngxià, Gānsù, Qīnghăi, and Xīnjiāng provinces).

The Government also includes the 5,000 Utsuls 回輝 people on the Hǎinán Island within the Huí nationality. Their ancestors are Austronesian Muslims who arrived from Vietnam during the Ming dynasty (AD 1368–1644). The Huí people have no indigenous language but speak Mandarin Chinese. As they are Muslims, part of their religious vocabulary differs from that of the Hàn Chinese.

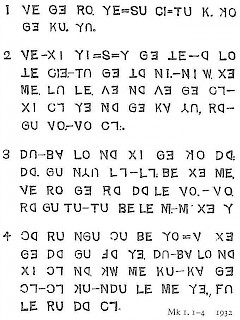

Huí Bible (2010)Information on the number of Huí Christians is unknown. In 2010, an anonymous mission organization published a Huí Bible in Hong Kong. The language of this Bible is similar to that of the Chinese Union Version (Hong Kong Bible Society) or Chinese New Version (World Wide Bible Society), except for keywords such as God, Jesus, or Christ. Some differences are listed below.

Huí Bible (2010)Information on the number of Huí Christians is unknown. In 2010, an anonymous mission organization published a Huí Bible in Hong Kong. The language of this Bible is similar to that of the Chinese Union Version (Hong Kong Bible Society) or Chinese New Version (World Wide Bible Society), except for keywords such as God, Jesus, or Christ. Some differences are listed below.

The differences relate to how the Huí people traditionally transliterate religious terms from Arabic into Chinese. For example, the term Màixīhā 麦西哈 is a transliteration of “Messiah” in Arabic or Hebrew, while the term Jīdū 基督 is a transliteration of “Christ” in Greek. The different choice for the name of God, “True Lord” (Huí) versus the polytheistic concept of Shén 神 (Hàn), is reminiscent of the nineteenth century when Protestant missionaries disagreed on using Shén 神 versus Shàngdì 上帝.

|

Huí Bible (2010) |

Chinese Union Version (1919) |

English |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 真主 | 神 |

God (Yahweh) |

Mt. 3:9 |

| 主 | 主 |

Lord |

Mt. 4:7 |

| 神明 | 神 |

god (not Yahweh) |

Jn. 10:35 |

| 尔撒 | 耶稣 |

Jesus |

Mt. 1:1 |

| 麦西哈 | 基督 |

Christ |

Mt. 1:17 |

| 麦西哈的弟子 | 基督徒 |

Christian |

Ac. 11:26 |

| 易卜劣厮 | 魔鬼 |

devil |

Mt. 4:1 |

| 天仙 | 天使 |

angel |

Mt. 13:39 |

| 佳音 | 福音 |

Good News |

Mt. 4:23 |

| 礼拜堂 | 会堂 |

Synagogue |

Mt. 4:23 |

| 哲玛提 | 教会 |

Church |

Mt. 16:18 |

| 坟坑 | 阴间 |

Hades |

Mt. 11:23 |

Table 5: Terms in Huí Bible

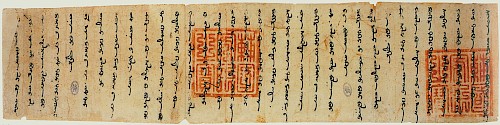

Altaic Minorities (5)

The Altaic languages are a sprachbund or family of about 67 languages of which the geographical origin is the Altai Mountains in Central East Asia, spanning over Russia, China, and Mongolia. The Altaic languages consist of three subgroups: the Turkic (42), the Mongolic (13), and the Tungusic (12) languages. Two Altaic peoples ruled over China: the Mongols during the Yuán dynasty 元朝 (1271–1368) and the Manchus during the Qīng dynasty 清朝 (1644–1911).

The subsequent table illustrates the portions of the Bible that were translated into five Altaic languages of China: one Mongolic, two Tungusic, and two Turkic languages.

|

ISO639-3 |

Language |

Classification |

Population |

Book |

NT |

Bible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

mvf |

Chahar-Mongolian 内蒙古语Chahar-Mongolian 内蒙古语, the language of Mongolians living in China, has linguistic differences from Khalka Mongolian, the official language of Mongolia. |

Altaic, Mongolic, Central |

3,380,000 |

|

2004There are three translations of the New Testament in the twenty-first century. The first version, called “Ariun Nom”, was completed in 2004 by a team, including Stefan Müller of Zentralasien-Gesellschaft. It is the version with the widest circulation in the churches of Inner Mongolia. The second version is a dynamic equivalence translation completed by members of the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), and was published in 2007 with the title “Shine Geree”. The third version was completed by Bao Xiaolin, a pastor of the Three-Self Church, in cooperation with the United Bible Societies and was published by Amity Press in 2013. |

|

|

mnc |

Manchu 满语Manchu 满语, a Southern Tungus language, was the primary language of the elite at the beginning of the Qīng Dynasty, but it went into steady decline thereafter. There are approximately 20 speakers remaining today in the Chinese Manchu nationality of more than 10 million people. |

Altaic, Tungusic, South |

20 |

1822Stepan Vaciliyevich Lipovtsov (1773–1841), an official of the Russian Foreign Office who studied Manchu for 20 years in China, translated the Gospel of Matthew into Manchu in 1822 prior to the final decline of Manchu in 1859. The British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) had 550 copies of the Gospel printed in St Petersburg, but only a few copies were distributed in China because the rest of the copies were destroyed in a flood. | 1835Stepan Lipoftsoff of the Russian Foreign Office translated the New Testament into Manchu by 1833, and George Borrow was appointed by the BFBS to help finalize the manuscript. In Beijing, George Borrow obtained an unpublished manuscript of the Manchu Old Testament, which the Jesuit missionary Louis Antoine de Poirot had completed in 1790. This manuscript enabled Borrow to learn the Manchu language in six months and to proofread Lipoftsoff’s New Testament. In 1835, the BFBS published the New Testament manuscript in St. Petersburg using Manchu characters. It has been reprinted often. |

|

|

evn |

Evenki 鄂温克语The Evenki 鄂温克语 language is also spoken by about 6,000 people in Russia. |

Altaic, Tungusic, North |

11,000 |

2002Nadezhda Bulatova and David Kheĭzell of the Institute for Bible Translation in Moscow translated the Gospel of Luke into the Tura dialect of Evenki in 2002. The manuscript was published by the Institute of Bible Translation (IBT) in Moscow in 2002 and republished as Evenki/Russian diglot with audio recording in 2013, making it usable for the Evenki in Inner Mongolia and Hēilóngjiāng, China. |

|

|

|

oui |

Old Uyghur 回鹘语The Modern Uyghur language is not developed from Old Uyghur 回鹘语. Instead, Modern Uyghur is a mixture of the literary Chagatai language and the speech of Kāshghar. What was called Old Uyghur developed into a distinct modern language, that is, Western Yugur. It was in the 1930s that the name of Uyghur was redefined. |

Altaic, Turkic, Southeast |

? |

|

1307The papal envoy John of Montecorvino, a Catholic missionary ahead of his time, translated the New Testament into Old Uyghur in 1307. John was based in Bĕijīng, where Old Uyghur was spoken as the lingua franca of the Mongol ruling elite. |

|

|

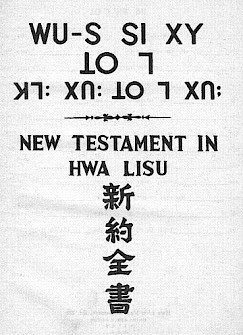

uig |

Modern Uyghur 维吾尔语The Modern Uyghur 维吾尔语 language is not derived from Old Uyghur. Instead, Modern Uyghur is a mix between the literary Chagatai language and the Kashgar speech. Old Uyghur has evolved into the modern Western Yugur language (the name Uyghur was redefined in the 1930s). |

Altaic, Turkic, Southeast |

8,400,000 |

1898The Gospels were first translated in 1898 by J. Avetaranian (Swedish Missionary Society) and published by the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) in Leipzig in the same year. | 1914The New Testament was translated by J. Avetaranian and G. Raquette (Swedish Missionary Society) and published in 1914 by the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) in Plovdiv (Bulgaria). | 1950In exile from Xinjiang, the first Bible was completed in 1950 by G. Ahlbert, O. Hermannson, Nur Luke, Moulvi Munshi, and Moulvi Fazil in India. It was published by the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) in Cairo in 1950. In 2005, the Uyghur Bible Society published a new translation of the New Testament and portions of the Old Testament. |

Table 6: Bible Translation in Altaic Languages of China

Among the Altaic groups, the Mongols 蒙古 assume a prominent historical role. Genghis Khan (1162–1227) founded the Mongol Empire in AvargaAvarga is located in Khentii Province, Mongolia. in 1206 and started the Mongol Invasions, which, at their peak in 1279, resulted in the conquest of most regions of Eurasia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. Yet, the Mongols endured a decisive defeat against the Muslim MamluksMamluks were slave-soldiers that Arab Fatimid Caliphs brought from Central Asian tribes to form their military elite corps, similar to the Légion étrangère (Foreign Legion). The Mamluks supplanted the Fatimids in 1174 and ruled over Egypt and the Middle East until the fifteenth century. in the Battle of Ain JalutAin Jalut, “Spring of Goliath,” is a place in the Jezreel valley of Southeastern Galilee. The European crusaders in Palestine allowed the Egyptian Mamluks to traverse it to fight the Mongols in 1260. See Cline (2002). of 1260.