Introduction

The Nuosu in Liángshān 凉山 prefecture of Sìchuān province constitute the largest homogenous group of the Yí (彝) nationality with about 2.5 Million members. No grouping uses Yí as a self-name. Perhaps 15% of the Yí population address themselves as Lolo or Lalo. The remaining tribes employ heterogenous names, such as Nuosu, Nisu, Nasu, Ni, Azhe, Kopho, Mutsi, Phula, Hlehle and so forth.

Great unanimity prevails among ethnographic writers that the genesis of the Yí groupings trace back more than 2000 years to an ancient group called Ni people. Early Chinese records referred to Southwestern peoples as Wūmán 乌蛮 (Black Barbarians) and Báimán 白蛮 (White Barbarians). Notably, these names may point to the basic color labels that apply to virtually every minority in Southwest China, including other groups such as the Miao, Tai, Lahu, Lisu, and not only the Yi. After the 12th century, Chinese sources gradually employed the name Lúo 猡 containing the pejorative animal radical. The name subsequently evolved into its reduplicated form Lolo. This name had been the designation used by Chinese and Westerners for several centuries until 1949 when, it was substituted by the name Yí 彝 with the arrival of the People’s Republic of China. In the language classification literature, Lolo survived within the group designation Loloish languages.

Culture

Memorial in Miǎnníng 冕宁 CountyRed Army's passage in Liángshān in 1935 (Memorial in Miǎnníng 冕宁 County).(A) History:The ancestors of the Nuosu have lived in the Liángshān 凉山 area since at least the Sòng dynasty (960-1279). The Nuosu caste society surfaced after the Mongols extended their subsidiary ruling system based on indigenous chieftains (土司 tŭsī) all across China in the 13th century. The emergence of the caste system probably directly pertains to the installment of indigenous chieftains by the imperial administration. The nzymo constituted a relatively small group of indigenous landowners who were chosen by the central government from several spots in Liángshān. While the nuoho caste constitutes a much larger class of ethnic aristocrats than the nzymo, it is not acknowledged by the central government. Further, as a third caste the quho caste consists of ordinary peopleA quho is associated with one nuoho and one nzymo; see Jiǎng Yìwén 蒋益文, 2010, “Bits on the History of the Yí nationality” “彝族历史点滴”, Bulletin of Chinese Nationalities, 15th of October, 2010 《中国民族报》,2010 年 10 月 15 日..

Memorial in Miǎnníng 冕宁 CountyRed Army's passage in Liángshān in 1935 (Memorial in Miǎnníng 冕宁 County).(A) History:The ancestors of the Nuosu have lived in the Liángshān 凉山 area since at least the Sòng dynasty (960-1279). The Nuosu caste society surfaced after the Mongols extended their subsidiary ruling system based on indigenous chieftains (土司 tŭsī) all across China in the 13th century. The emergence of the caste system probably directly pertains to the installment of indigenous chieftains by the imperial administration. The nzymo constituted a relatively small group of indigenous landowners who were chosen by the central government from several spots in Liángshān. While the nuoho caste constitutes a much larger class of ethnic aristocrats than the nzymo, it is not acknowledged by the central government. Further, as a third caste the quho caste consists of ordinary peopleA quho is associated with one nuoho and one nzymo; see Jiǎng Yìwén 蒋益文, 2010, “Bits on the History of the Yí nationality” “彝族历史点滴”, Bulletin of Chinese Nationalities, 15th of October, 2010 《中国民族报》,2010 年 10 月 15 日..

The Red Army passed on its Long March through the Liángshān area in April 1935; the relatively smooth traversal enabled the Nuosu to gain credit with the Central Government after the People’s Republic was founded in 1949. In the aftermath, Liángshān was established as Yí autonomous prefecture and Xichang was announced as its capital. The caste society was also abolished. In 1957-59, at the time of the Great Leap Forward, a rebellion of disillusioned Yí leaders broke out and was subsequently defeated.

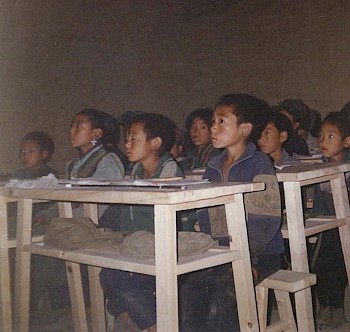

During the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976, ethnic culture was systematically suppressed, something that happened all over China, before experiencing revival in the 1980s. In 1978, the Government standardized and issued an official Nuosu syllabary of 1119 characters in which bilingual Nuosu-Han education was sponsored. Against the backdrop of Maó Zédōng’s 毛泽东 great investigation into Chinese minority peoples in the 1950s, Nuosu was one of the few groups whose writing system was officially recognized.

(B) Customs: Nuosu society is organized along two coordinates: the clan and caste orders. Nuosu society is a clan order of patrilineal lineageSee Harrel, S., 2001, Ways of being ethnic in Southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press..

Nuosu bride awaits bridegroomEvery Nuosu belongs to one clan associated with one caste. Each caste consists of several clans. The number of clans inhabiting a given area is limited and known to the residents of that specific region. Solidarity among clan members is a social imperative. Nuosu clans are exogamous and marriage between clans serves the purpose of establishing kinship networks. Male and female membership to a clan is inherited from the father, and through marriage, respectively.

Nuosu bride awaits bridegroomEvery Nuosu belongs to one clan associated with one caste. Each caste consists of several clans. The number of clans inhabiting a given area is limited and known to the residents of that specific region. Solidarity among clan members is a social imperative. Nuosu clans are exogamous and marriage between clans serves the purpose of establishing kinship networks. Male and female membership to a clan is inherited from the father, and through marriage, respectively.

Nuosu clans are associated with one of three castes: nzymo, nuoho or quho. The nzymo caste consists of less than one percent of the Liángshān population; they are the descendants of former aristocrats who were recognized by the imperial government.

Similarly, the nuoho caste consists of the descendants of former aristocrats who were not recognized by the imperial government. Meanwhile the quho caste comprises of independent farmers. The clans within a caste are exogamous but each caste is strictly endogamous. A nzymo marries a nzymo, a nuoho marries a nuoho and a quho marries a quho. Following the takeover in 1949, economic facets of the caste system were abolished but knowledge of the castes survives until today.

Besides these three strata, there is a fourth caste, the ga xy houseslaves, which are not associated with any clan. They are the descendants of people who were captured as slaves from the Han area, or of aliens that ventured into Nuosu territory without adequate local protection. Through this four-way caste system, the Nuosu has attained a prominent position among ethnic groups in China. As a matter of fact, communist writers before and after the Cultural Revolution used Nuosu society as an illustration for the Marxist theory of social evolution in which societies pass from the primitive to the feudal stage.

Nuosu Torch Festival in JulyIn addition to clans and casts, the Nuosu society acknowledges several social officesSee Harrel, S., 2001, Ways of being ethnic in Southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. that are not connected to the descent of the holder: surgga ‘wealthy person’, ndeggu ‘mediator’, ssakuo ‘warrior’, gemo ‘craftman’, bimo ‘priest’, and sunyi ‘shaman’. The surgga denotes an individual whose material possessions in land, livestock, and slaves accord him a recognized status as an entrepreneur. Meanwhile the ngeddu is a person with a special track record in mediating social conflicts. In traditional society, the ssakuo signifies a warrior who has proven as a victorious hero on the battlefield. The gemo on the other hand, is a craftsman, either a blacksmith, or a gold or silversmith.

Nuosu Torch Festival in JulyIn addition to clans and casts, the Nuosu society acknowledges several social officesSee Harrel, S., 2001, Ways of being ethnic in Southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. that are not connected to the descent of the holder: surgga ‘wealthy person’, ndeggu ‘mediator’, ssakuo ‘warrior’, gemo ‘craftman’, bimo ‘priest’, and sunyi ‘shaman’. The surgga denotes an individual whose material possessions in land, livestock, and slaves accord him a recognized status as an entrepreneur. Meanwhile the ngeddu is a person with a special track record in mediating social conflicts. In traditional society, the ssakuo signifies a warrior who has proven as a victorious hero on the battlefield. The gemo on the other hand, is a craftsman, either a blacksmith, or a gold or silversmith.

Across the Liángshān area, the Nuosu celebrate the Torch Festival in the month of July. According to a mythical legend, the Yí ancestors combated pests sent by the god Entiguzi in order to destroy their crops. By holding up torches, they were able to defeat the pests and the god who sent them. Every year in the Month of the Dog and on the day chosen by the bimo, torches are lit to commemorate the victory.

Religion

(A) Traditional Religion: The Nuosu religion is a folk religion based on polytheistic and animist beliefs. The Nuosu recognize the name of several gods and also use the generic term si or si sse for unknown deities.

Nuosu priest (bimo)The term Momu Apo ‘Father of Heaven’ designates the creator of the universe. Zhege'alu is another powerful god who came into existence after the Great Flood and eventually went out of existence before the arrival of the present time. Some of the gods are evil, similar to evil spirits that move about. In addition to gods, the Nuosu both venerate and fear the spirits of their ancestors. This is because ancestors are believed to have three spirits that ultimately return to their separate homes after death; the individual spirit, the family spirit, and the clan spirit. Ancestral spirits who are unable to do so are believed to come back and harass the living people. In this regard, the role of the bimo, the Nuosu priest, is to read ritual texts aloud at funerals that guide the deceased soul safely back to the ancestral place in the after-world.

Nuosu priest (bimo)The term Momu Apo ‘Father of Heaven’ designates the creator of the universe. Zhege'alu is another powerful god who came into existence after the Great Flood and eventually went out of existence before the arrival of the present time. Some of the gods are evil, similar to evil spirits that move about. In addition to gods, the Nuosu both venerate and fear the spirits of their ancestors. This is because ancestors are believed to have three spirits that ultimately return to their separate homes after death; the individual spirit, the family spirit, and the clan spirit. Ancestral spirits who are unable to do so are believed to come back and harass the living people. In this regard, the role of the bimo, the Nuosu priest, is to read ritual texts aloud at funerals that guide the deceased soul safely back to the ancestral place in the after-world.

Ancestor worship is practiced on special occasions with offerings of wine, meat, pigs’ heads, and eggs, among others. Witchcraft and black magic, mainly in the form of incantations, are an integral element of religious practices. They manifest their impact by affecting both physical objects and people, curing illnesses, casting out demons, fortune telling, divining using the innards of sheep, pigs, chicken, and so forth.

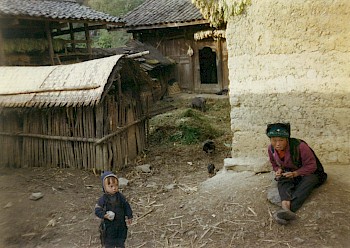

Nuosu farmThe bimo ‘priest’ and sunyi ‘shaman’ are ministers of the Nuosu folk religion. The bimo performs all kind of rituals, especially death rituals, through the reading or chanting of texts. Bimo are male, are almost always quho, and are considered to be the guardians of the Nuosu traditional script. The office of bimo is acquired through a long process of apprenticeship.

Nuosu farmThe bimo ‘priest’ and sunyi ‘shaman’ are ministers of the Nuosu folk religion. The bimo performs all kind of rituals, especially death rituals, through the reading or chanting of texts. Bimo are male, are almost always quho, and are considered to be the guardians of the Nuosu traditional script. The office of bimo is acquired through a long process of apprenticeship.

Meanwhile the sunyi is a shaman whose experience is not acquired through ritual texts, but via interaction with the spiritual world. The office of sunyi is not contingent upon caste, clan or gender. The sunyi enters trance and becomes possessed by spirits when they are called upon to perform rituals such as exorcising or curing diseases.

(B) Disciples’ Congregation 门徒会: The Disciples’ Congregation 门徒会Another name for this movement is “Religion of the Christ of Three Redemptions” (“三赎基督教”).

See Kupfer, K. (2001). ‘Geheimgesellschaften’ in der VR China: Christlich inspirierte, spirituell-religöse Gruppierungen seit 1978. China Analysis No. 8. Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies. University of Trier, Germany.

Anonymous, 2000, Change among the Nuosu. MA Thesis, USA. is an eschatological movement that was established in 1989. Its founder Jì Sānbăo 季三宝 (1939-1997) was a native of Xī’ān 西安The city name Xī’ān 西安 is homophonous to the term Xī’ān 锡安, used in the Chinese Union Version to transliterate Zion in Jerusalem (see Second Book of Samuel 5:7). in Shaanxi province. In the 1980s, he approached a Three-Self Church when suffering from personal illness. Upon getting cured, he started to tour villages with a mission of healing others. He and his wife Xŭ Míngcháo 许明潮 adopted religious names, Sānshú 三赎Sānshú 三赎 means “Three Redemptions”. Sānshú alone has the power of redeeming sins passed on to him from members of the movement. The significance of the number “three” in “three redemptions” remains unknown, but might refer to the leader’s secular name. and Xŭshú 许赎Xŭshú 许赎 means “promise and redemption”.. Sānshú claimed to be the reincarnation of Jesus Christ, the second person of the Trinity. Meanwhile Xŭshú was declared to be the Holy Spirit, the third person of the Trinity. Sānshú had predicted that the world would come to an end in 2000, before he was killed in a car accident in 1997. He was succeeded by new leaders, Yù Shìqiáng 蔚世强 (1997-2001) and Chén Shìróng 陈世荣 (2001-today).

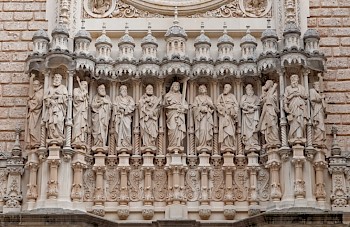

The 12 DisciplesThe 12 Disciples at the Montserrat Monastery in Spain.Sānshú surrounded himself with 12 disciples who oversaw a network of thousands of secretive assemblies. By 1995, there had been reportedly more than 700,000 adepts in 12 provinces of the P.R. of China, mainly in rural areas. After 1994, the Disciples’ Congregation 门徒会 made adherents among the NuosuSee Anonymous, 2000, Change among the Nuosu. MA Thesis. in Liángshān. According to one account, there were about 100,000 Nuosu followers by the year 2000, 5% of the Nuosu population. The number decreased again in the following years as the Nuosu took cognizance of the fact that this movement was not mainstream Christianity. As a result, Nuosu leaders of important disciples’ congregations turned to protestant-style churches that developed in Liángshān after 2000. They then drew thousands of their supervised Nuosu away from the disciples’ movement.

The 12 DisciplesThe 12 Disciples at the Montserrat Monastery in Spain.Sānshú surrounded himself with 12 disciples who oversaw a network of thousands of secretive assemblies. By 1995, there had been reportedly more than 700,000 adepts in 12 provinces of the P.R. of China, mainly in rural areas. After 1994, the Disciples’ Congregation 门徒会 made adherents among the NuosuSee Anonymous, 2000, Change among the Nuosu. MA Thesis. in Liángshān. According to one account, there were about 100,000 Nuosu followers by the year 2000, 5% of the Nuosu population. The number decreased again in the following years as the Nuosu took cognizance of the fact that this movement was not mainstream Christianity. As a result, Nuosu leaders of important disciples’ congregations turned to protestant-style churches that developed in Liángshān after 2000. They then drew thousands of their supervised Nuosu away from the disciples’ movement.

The publication of the New Testament in 2005 contributed further to its precipitous decline. An anonymous analyst attributes the successful spread of the Disciples’ movement among the Nuosu to their sense of insecurity in the age of modernity on the one hand, and to the definite beliefs in sin, judgment, salvation, hell and heavenThe following doctrines are derived from interviews conducted by an anonymous analyst with leaders of the Disciples’ Congregation. Sin refers to any disobedience to Sānshú or his appointed leaders, in particular any breach to the prohibition of eating more than a quarter pound of rice per day. Every follower whose sins are forgiven by Sānshú, who respects the regulations of the Disciples’ Congregation, and who has bought the symbolic key of Heaven, is saved. The salvation of ordinary people is determined on a day of judgment. Hell is the place where a person burns in sulfur for eternity. Heaven is the sphere where the saved souls will be dressed in white clothes, partake of the bread of life, live in praise and worship, and serve Sānshú as well as his leaders. articulated by the Disciples’ Congregation on the other hand.

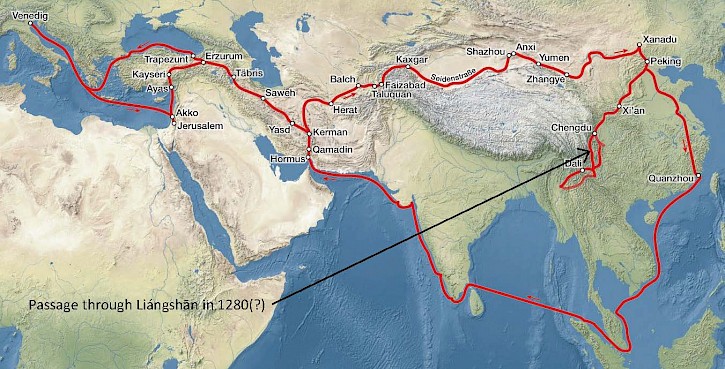

(C) Christianity: The first European travelling through the Liángshān area was the Venetian traveler Marco Polo 马可·波罗 (1254-1324). During his trip to China (1271-1295), he was welcomed by Kublai Khan, the first emperor of the Yuán Dynasty 元朝 (1271-1368). Possibly employed as an imperial official, he travelled several times to the southern provinces.

Statue of Marco PoloStatue of Marco Polo in Hángzhōu 杭州, Zhèjiāng 浙江 Province.

Statue of Marco PoloStatue of Marco Polo in Hángzhōu 杭州, Zhèjiāng 浙江 Province.

Travels of Marco Polo (1271-1295)

Travels of Marco Polo (1271-1295)

In his book Description of the WorldMarco Polo’s Description of the World was translated and edited by Moule and Pelliot in 1938. See

Moule, A.C and Pelliot, P., 1938, Marco Polo: The Description of the World. Translated and edited. London: George Routledge and Sons., written in Latin after his return to Venice in 1295, Marco Polo describes one journey from Chéngdū 成都 (Sìchuān) to Yúnnán where he passed through Liángshān, possibly close to the year 1280. He does not directly mention the ancestors of the Nuosu.

In the 1860s, François Louis Crabouillet (1837-1904), Catholic missionary of the Missions Étrangères de Paris, was appointed to Liángshān. He published an ethnographic descriptionSee Crabouillet, F. L., 1873, “Les Lolos”. Les Missions Catholiques Tome V, pp. 71-72, 93-94, 105-107. Lyon. of the Nuosu in 1872 and evangelized the Nuosu for almost 30 years. Vicomte D’Ollone, a major in the French army, reported in his travels to Southwest China (1906-1909) that there were several Catholic mission posts in Liángshān, in Huìlĭ 会理, Déchāng 德昌 and Xīchāng 西昌. The duration of the existence of these Catholic mission stations remains unknown.

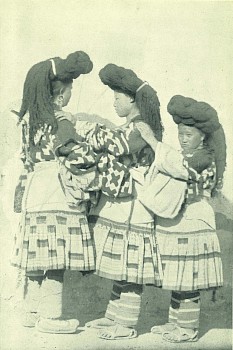

Nuosu women in 1903Nuosu women in 1903 with wool plaited into the hair.Noted English diplomat Edward Colborne BaberSee Baber, E. C., 1882, Travels and researches in Western China. London: Royal Geographical Society Supplementary Papers. (1843-1890) travelled to Liángshān in 1878. George Nicoll 李格尔 and Charles Leaman 李满 of the China Inland Mission 内地会 also made explorative trips from Chóngqìng 重庆 into the Liángshān area in 1878. Alexander Hosie 谢立山, another diplomat stationed with the British consular service in Chóngqìng 重庆, made three expeditions through the area, in 1882, 1883 and 1884, respectively.

Nuosu women in 1903Nuosu women in 1903 with wool plaited into the hair.Noted English diplomat Edward Colborne BaberSee Baber, E. C., 1882, Travels and researches in Western China. London: Royal Geographical Society Supplementary Papers. (1843-1890) travelled to Liángshān in 1878. George Nicoll 李格尔 and Charles Leaman 李满 of the China Inland Mission 内地会 also made explorative trips from Chóngqìng 重庆 into the Liángshān area in 1878. Alexander Hosie 谢立山, another diplomat stationed with the British consular service in Chóngqìng 重庆, made three expeditions through the area, in 1882, 1883 and 1884, respectively.

Visitors to the Liángshān area had to arrange for guarantors 保头, which was the usual procedure for outsiders to visit the area. In 1909, the British Donald Burk was killed by the Nuosu and those with him that were sold as slaves, since he was not accompanied by a local guarantor.

Samuel Pollard 柏格理 (1864-1915), a missionary to the Ahmao people in Western Guìzhōu, explored the Liángshān area during a period of six weeks in 1903. He was the first EuropeanSee Pollard, W., 1928, The life of Sam Pollard of China. London: Seeley. to cross into Liángshān over the Golden Sand River 金沙河.

In the 1940s, several protestant mission societies commenced their work in Liángshān. The Conservative Baptist Foreign Mission SocietyThe Conservative Baptist Foreign Mission Society (CBFMS) was formed in Chicago, Illinois, in 1943. It was renamed Conservative Baptist International in 1994, and then World Venture in 2005. appointed Ralph Covell 柯饶富 (1923-2013) and Lee Lovegren 任福根 to Xīchāng 西昌 in Liángshān in 1947/1948 with the aim to translate the Bible.

Ralph and Ruth CovellThey joinedSee Covell, R., 1990, Mission Impossible. The unreached Nosu on China’s Frontier. Pasadena: Hope Publishing House. two English Baptist missionaries as well as five co-workers of the China Inland Mission who were already on the site. Both Covell and Lovegren learnt Nuosu with local teachers and established a missionary outpost at Lúgū Lake 泸沽湖. During 1949 and 1950, the general situation for foreigners deteriorated and missionary workers started to get harassed. Lovegren was imprisoned on account of spy charges in February 1951, and a mother of four children in their group passed away in June 1951. Covell was deported to Hong Kong where he arrived in July 1951. From 1951 to 1966, Covell settled in Taiwan where he translated the New Testament and portions of the Old Testament into the Seediq languageThe Seediq 赛德克 language is a Northern Formosan (Austronesian) language spoken by 20,000 people in Nántóu 南投 and Huālián 花蓮 counties of Taiwan.. From 1966 to 1990, Covell served as the professor of missiology at the Conservative Baptist Seminary in Denver, Colorado.

Ralph and Ruth CovellThey joinedSee Covell, R., 1990, Mission Impossible. The unreached Nosu on China’s Frontier. Pasadena: Hope Publishing House. two English Baptist missionaries as well as five co-workers of the China Inland Mission who were already on the site. Both Covell and Lovegren learnt Nuosu with local teachers and established a missionary outpost at Lúgū Lake 泸沽湖. During 1949 and 1950, the general situation for foreigners deteriorated and missionary workers started to get harassed. Lovegren was imprisoned on account of spy charges in February 1951, and a mother of four children in their group passed away in June 1951. Covell was deported to Hong Kong where he arrived in July 1951. From 1951 to 1966, Covell settled in Taiwan where he translated the New Testament and portions of the Old Testament into the Seediq languageThe Seediq 赛德克 language is a Northern Formosan (Austronesian) language spoken by 20,000 people in Nántóu 南投 and Huālián 花蓮 counties of Taiwan.. From 1966 to 1990, Covell served as the professor of missiology at the Conservative Baptist Seminary in Denver, Colorado.

No significant effort could be undertaken to evangelize the Nuosu between 1951 and 1990. During the 1990s, a missionary of New Tribes Mission privately translated the four Gospels into Nuosu. However, he had to depart from Liángshān without publishing his work. From 1996 to 2005, members of RFLRSee Research Foundation Language and Religion. translated the New Testament into Nuosu. The first edition was published in 2005, which was followed by a revised version in 2009. A short sketch of the translation process is presented on this webpage.

Language

(A) General information: The data presented in this section originates from Gerner (2013). Nuosu belongs to the Burmese-Lolo language group within the Tibeto-Burman language family, as illustrated on the following map. Liángshān Nuosu has five dialects: Shynra, Suondi, Adur, Yynuo, and Lindimu. Shynra has the highest number of speakers with more than one million speakers and is the standard dialect sponsored by the Government. Nuosu in the Burmish-Lolo Group

Nuosu in the Burmish-Lolo Group

|

County/municipality |

Population |

Shynra |

Suondi |

Adur |

Yynuo |

Lindimu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Xīchāng 西昌 |

818,033 |

71,400 |

10,200 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Mùlĭ 木里藏族自治县 |

195,938 |

51,000 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Yányuán 盐源县 |

469,674 |

212,500 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Déchāng 德昌县 |

286,574 |

13,600 |

51,000 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Huìlĭ 会理县 |

676,360 |

--- |

105,400 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Huìdōng 会东县 |

566,111 |

--- |

79,900 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Níngnán 宁南县 |

260,844 |

--- |

54,400 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Pŭgé 普格县 |

221,630 |

--- |

68,000 |

93,500 |

--- |

--- |

|

Bùtuō 布拖县 |

220,991 |

--- |

--- |

205,700 |

--- |

--- |

|

Jīnyáng 金阳县 |

214,332 |

--- |

83,300 |

71,400 |

11,900 |

--- |

|

Zhāojué 昭觉县 |

349,996 |

117,300 |

96,900 |

30,600 |

86,700 |

--- |

|

Xĭdé 喜德县 |

207,478 |

173,400 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Miănníng 冕宁县 |

474,624 |

142,800 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

Yuèxī 越西县 |

363,674 |

239,700 |

--- |

--- |

5,100 |

--- |

|

Gānluò 甘洛县 |

266,847 |

15,300 |

--- |

--- |

86,700 |

69,700 |

|

Měigū 美姑县 |

261,215 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

251,600 |

--- |

|

Léibō 雷波县 |

361,953 |

--- |

--- |

40,800 |

119,000 |

--- |

|

Total for Liángshān: |

6,216,281 |

1,037,000 |

549,100 |

442,000 |

561,000 |

69,700 |

Table 1: The five Nuosu dialects in Liángshān 凉山

(B) Rare properties: Nuosu exhibits several rare features in its grammar, that is in its morphological, its syntactic and its pragmatic system.

1. Morphology: A sound symbolism is associated with Nuosu. For a closed set of gradual antonym pairs, prefixing i- to an adjectival root yields the diminutive member, whereas prefixing a- to the same root gives the augmentative member of that pair.

|

[i] diminutive |

[a] augmentative |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ꀁꎴ |

ix sho |

‘short’ |

ꀊꎴ |

a sho |

‘long’ |

| ꀁꄖ |

ix du |

‘thin’ |

ꀊꄖ |

a du |

‘thick’ |

| ꀁꇖ |

ix ly |

‘light’ |

ꀊꇖ |

ax ly |

‘heavy’ |

| ꀁꐯ |

ix jjy |

‘narrow’ |

ꀊꐯ |

a jjy |

‘wide’ |

| ꀁꑌ |

ix nyi |

‘few’ |

ꀉꑌ |

ax nyi |

‘much, many’ |

| ꀁꃚ |

ix fu |

‘fine’ |

ꀊꃚ |

a fu |

‘coarse’ |

| ꀁꆓ |

ix nu |

‘soft’ |

ꀉꇨ |

ax guo |

‘hard’ |

| ꀄꊭ |

iet zyr |

‘small’ |

ꀉꒉ |

ax yy |

‘big’ |

Table 2: The Nuosu diminutive/augmentative sound symbolism

Nuosu exhibits an African-style logophor with two suppletive singular/plural forms i / opi ꀂ is the singular logophor and op ꀒ the plural logophor.. These two logophors monitor the source whose speech is reported. (The referents of noun phrases are indicated by number subscripts.)

|

(1) |

a. |

ꇐꄿ1ꃅꇤꏭꉉꇬꀂ1 ꐝꈷꀐꄷ。 |

||||||||

|

|

|

lu dda1 |

mu ga |

jox |

hxip |

go |

i1/*2/*3 |

jjiex mguo |

ox |

ddix. |

|

|

|

Ludda |

Muga |

to |

say |

SENT.TOP |

LOG.SG |

clear |

DP |

QUOT |

|

|

|

'Ludda1 told Muga that he1 understood it clearly.' |

||||||||

|

|

b. |

ꃅꏸꇐꄿ1ꄷꄉꈨꇬꀒ1ꐝꈯꀐꄷ。 |

|||||||||

|

|

|

mu jy |

lu dda1 |

ddix |

da |

gge |

go |

op1 |

jjiex mguo |

ox |

ddix. |

|

|

|

Mudje |

Ludda |

at |

COV |

hear |

SENT.TOP |

LOG.PL |

clear |

DP |

QUOT |

|

|

|

'Mudje heard from Ludda1 that they1 understood it clearly.' |

|||||||||

Definite articles are derived from classifiers with the nominalizer -su ꌠ.

|

(2) |

a. |

ꊿꂷ |

|

b. |

ꊿꂶꌠ |

||

|

|

|

co |

ma |

|

|

co |

max su |

|

|

|

man |

CL |

|

|

man |

ART=CL-DET |

|

|

|

'a man' |

|

|

'the man' |

||

|

|

c. |

ꁮꏂꏢ |

d. |

ꁮꏂꏡꌠ |

|||

|

|

|

bbu shy |

ji |

|

bbu shy |

jix su |

|

|

|

|

snake |

CL |

|

snake |

ART=CL-DET |

|

|

|

|

'a snake' |

|

'the snake' |

|||

The Nuosu predicate is marked by aspectual verb suffixes. Bare verbs are both allowed and frequent. In this context, one Nuosu aspect suffix is typologically exceptional. The exhaustion particle sat ꌐ targets three kinds of structure: the clause-initial NP upon which it acts as a universal quantifier (‘all’), the VP that it modifies as completive marker (‘completely’), and the AP upon which it contributes the meaning of superlative (‘most’).

|

(3) |

a. |

ꊿꉆꑼꌠꐯꇯꄯꒉꉜꌐ。 |

||||||

|

|

|

co |

hxit |

yuop su |

jjy gex |

tep yy |

hxep |

sat. |

|

|

|

people |

NUM.8 |

ART=CL-DET |

together |

book |

see, read |

EXH |

|

|

|

'The eight people are all reading books.' |

||||||

|

|

b. |

ꋀꊇꌧꂓꊰꂷꋠꌐꀐ。 |

||||||

|

|

|

cop wox |

syp hmi |

ci |

ma |

zze |

sat |

ox. |

|

|

|

3P.PL |

nut |

NUM.10 |

CL |

eat |

EXH |

DP |

|

|

|

(i) 'They all ate ten nuts.' (ii) 'They completely ate up ten nuts.' (iii) 'They all ate up ten nuts.' |

||||||

|

|

c. |

ꀂꄁꀊꋨꈫꄈꎔꌐ。 |

|

|||||

|

|

|

i dix |

a zzyx |

ggux |

dax |

nrat |

sat. |

|

|

|

|

garment |

DEM.DIST |

CL |

COV |

beautiful |

EXH |

|

|

|

|

'That garment is the most beautiful.' |

||||||

2. Syntax: For simple clauses, Nuosu exhibits a rare aspect-conditioned word order split: SOV order in ongoing (roughly imperfective) clauses and OSV in resultative (roughly perfective) clauses.

|

(4) |

|

SOV order in Ongoing clauses |

|||

|

|

a. |

ꀈꑘꃅꎓꇁꉚꐺ。 |

|||

|

|

|

at nyop |

mu rryr |

la hxex |

njuo. |

|

|

|

Anyuo |

Mudge |

wait |

PROG |

|

|

|

'Anyo is waiting for Mudge.' |

|||

|

|

|

OSV order in Resultative clauses |

||||

|

|

b. |

ꀈꑘꃅꇤꊌꂿꀐ。 |

||||

|

|

|

at nyop |

mu ga |

wep |

mo |

ox. |

|

|

|

Anyuo |

Muga |

GET |

see |

DP |

|

|

|

'Anyo was seen by Muga.' |

||||

3. Pragmatics: Nuosu exhibits two topic particles: ne ꆏ communicates maintaining topic and li ꆹ contrastive topic. Both particles are associated with the sentence-initial NP.

|

(5) |

a. |

ꃴꑘꆏꃅꏦꀋꌧꀱꋦ。 |

|||||

|

|

|

vut nyop |

ne |

mu jie |

ap- |

syp |

bur zzur. |

|

|

|

female name |

TOP |

male name |

NEG- |

know |

seem |

|

|

|

'As for Vunyo, she appears not to know Mujie.' |

|||||

|

|

b. |

ꀊꑱꆹꎃꐚꃅꅇꉉ。 |

|||||

|

|

|

a yit |

li |

rrop jji |

mu |

ddop |

hxip. |

|

|

|

female name |

TOP |

natural |

ADVL |

word |

say |

|

|

|

(Differently from what you might think) 'Ayi spoke naturally.' |

|||||

(C) Writing system: The data presented here originate from (Gerner, 2013).

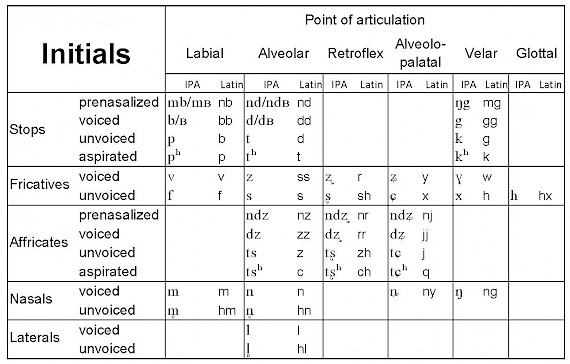

1. Consonants: Nuosu exhibits 43 consonant phonemes that are presented below in both the Romanized script (Nuosu Pinyin) and the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Remarkable features of the consonant system are the four types of fully contrastive phonation: prenasalized, voiced, unvoiced, and aspirated. A rare sound is the labial trill [B], which represents an allophone of [b]. Contrastive sets of words are presented below for each phonation type and point of articulation.

|

nb |

bb |

b |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

nbi ‘distribute’ |

bbi ‘spread’ |

bi ‘read’ |

pi ‘cut open’ |

|

nbie ‘shoot’ |

bbie ‘penis’ |

bie ‘kick’ |

pie ‘malaria’ |

|

nba ‘bundle’ |

bba ‘carry on back’ |

ba ‘exchange’ |

pat ‘hatch out’ |

|

nbo ‘roll’ |

bbo ‘go, leave’ |

bo ‘rent’ |

po ‘escape’ |

|

nbu ‘curse’ |

bbu ‘exist’ |

bu ‘porcupine’ |

pu ‘price’ |

|

nbur ‘full’ |

bbur ‘write’ |

bur ‘return; again’ |

pur ‘turn over’ |

|

nd |

dd |

d |

t |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ndi ‘contain’ |

ddi ‘bad, rotten’ |

di ‘single, alone’ |

ti ‘mean, signify’ |

|

ndie ‘skillful’ |

ddie ‘make’ |

die ‘layer’ |

tie ‘nominalizer’ |

|

ndat ‘enough’ |

ddat ‘accept’ |

da ‘put’ |

ta ‘earthern jar’ |

|

ndo ‘drink’ |

ddop ‘word’ |

dop ‘point at’ |

to ‘cut swiftly’ |

|

ndu ‘dig’ |

ddu ‘home’ |

dut ‘step on’ |

tut ‘family’ |

|

ndur ‘shake grain’ |

ddur ‘exit’ |

dur ‘thousand’ |

tur ‘chop up’ |

|

mg |

gg |

g |

k |

|---|---|---|---|

|

mgie ‘tell lies’ |

ggie ‘break’ (intr.) |

gie ‘guess’ |

kie ‘chop’ |

|

mga ‘pass’ |

gga ‘road’ |

ga ‘drop, shake’ |

ka ‘want’ |

|

mguo ‘embroider’ |

gguo ‘rake’ |

guo ‘fierce’ |

kuo ‘brave’ |

|

mge ‘buckwheat’ |

gge ‘hear’ |

ge ‘foolish’ |

ke ‘dog’ |

|

mgu ‘love, like’ |

ggu ‘nine’ |

gu ‘call’ |

ku ‘steal’ |

|

mgur ‘pick up’ |

ggur ‘frightened’ |

gur ‘frighten’ |

kur ‘year, age’ |

|

f |

v |

w |

|---|---|---|

|

fat ‘set free’ |

va ‘chicken’ |

wat ‘saddle’ |

|

pu fox ‘mislead’ |

vo ‘snow’ |

wo ‘bear’ |

|

fut ‘six’ |

vu ‘go crazy’ |

|

|

fur ‘pour’ |

vur ‘enter’ |

|

|

fy ‘ugly’ |

vy ‘buy’ |

|

|

ss |

s |

r |

sh |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ssa kuo ‘hero’ |

sat ‘mark, sign’ |

ra ‘make noise’ |

sha ‘splash’ |

|

|

suo ‘three’ |

ruop ‘pull trigger’ |

shuo ‘scrape’ |

|

sso ‘study’ |

sot ‘breath’ |

ro ‘frugal’ |

sho ‘harvest’ |

|

ssut ‘mix’ |

su (nominalizer) |

rup ‘unlucky’ |

shut ‘remember’ |

|

ssy ‘lifetime’ |

sy ‘blood’ |

ry ‘early’ |

shy ‘gold’ |

|

ssyr ‘press down’ |

syr ‘sweep’ |

ryr ggur ggur ‘firm’ |

shyr ‘yell’ |

|

y |

x |

w |

h |

|---|---|---|---|

|

yit ‘needle’ |

xi ‘arrive’ |

|

hit ‘harm’ |

|

yuo (classifier) |

xuo ‘slip, slide’ |

wuo ‘pull up’ |

huo ‘pour’ |

|

yo ‘sheep’ |

xop ‘leak out’ |

wo ‘group’ |

ho ‘pen, fold’ |

|

|

|

we ‘strength’ |

he ‘good’ |

|

yy ‘water’ |

xy ‘foot’ |

|

|

|

x |

h |

hx |

|---|---|---|

|

xit ‘bite’ |

hit ‘harm’ |

hxit ‘eight’ |

|

xie ‘catch fish’ |

|

hxie mat ‘heart’ |

|

xuo ‘slip, slide’ |

huop lyt ‘apricot’ |

hxuo ‘mix, add’ |

|

xop ‘leak out’ |

hot ‘bow’ |

hxo ‘grow, raise’ |

|

nz |

zz |

z |

c |

|---|---|---|---|

|

nzi ‘hammer nails’ |

zzi ‘bridge’ |

zi ‘leave over’ (tr.) |

ci ‘fall’ |

|

nzie ‘chop’ |

zzie ‘drench’ |

zie ‘compensate’ |

cie ‘deer’ |

|

nza ‘sing (of bird)’ |

zza ‘crops, food’ |

za pux ‘earth wall’ |

ca ‘hot’ |

|

nze ‘pretty’ |

zze ‘eat’ |

zep ‘tighten’ |

ce ‘salt’ |

|

nzup ‘armful of’ |

zzu ‘jab, poke’ |

zut ‘stir up’ |

cu ‘fat’ |

|

nzur ‘hate’ |

zzur ‘reside, live’ |

zur bop ‘origin’ |

cur ‘build’ |

|

nzy ‘rule’ |

zzy ‘ride (horse)’ |

zy ‘plant’ |

cy ‘wash’ |

|

nzyr ‘hot’ |

zzyr muo ‘peace’ |

zyr ‘accumulate’ |

cyr ‘pinch’ |

|

nr |

rr |

zh |

ch |

|---|---|---|---|

|

nra ‘measure, test’ |

rrax ggie ‘aligned’ |

zha ‘feed’ |

cha ‘discuss’ |

|

nro ‘stuff in’ |

rro ‘accomodate’ |

zhot ‘despise’ |

chop ‘breakfast’ |

|

nrep ‘withdraw’ |

rre ‘row’ |

zhep ‘bowl’ |

che ‘rice’ |

|

nrut ‘rust’ |

rrup ‘chopsticks’ |

zhu ‘praise’ |

chu ‘thorn’ |

|

nrur ‘lock’ |

rrur ‘lie about’ |

zhur ‘whet’ |

mu chur ‘autumn’ |

|

nry ‘wine’ |

rry ‘tooth’ |

zhy ‘command’ |

chy ‘bequeath’ |

|

nryr ‘pierce’ |

rryr ‘worn out’ |

zhyr ‘pull up’ |

chyr ‘tear’ |

|

nj |

jj |

j |

q |

|---|---|---|---|

|

nji ‘fast’ |

jji ‘fly’ |

ji (classifier) |

qi ‘want’ |

|

njie ‘vomit’ |

jjie ‘burn’ (intr.) |

jie ‘burn’ (tr.) |

qie ‘jump’ |

|

njuo ‘wander’ |

jjuo ‘collapse’ |

juo ‘press flat’ |

quo ‘navel’ |

|

njo ‘make level’ |

jjo ‘have, exist’ |

jo ‘turn’ |

qo ‘contain’ |

|

nju ‘crawl’ |

jjut ‘waist’ |

ju ‘manage’ |

qu ‘silver’ |

|

njurx zuo ‘expell’ |

jjur (classifier) |

jur ‘marrow’ |

qur ‘shave’ |

|

njy ‘skin’ |

jjy ‘melt’ |

jy ‘bladder, gall’ |

qy ‘sweet’ |

|

m |

n |

ny |

ng |

|---|---|---|---|

|

mit ‘hungry’ |

nit ‘your’ |

nyi ‘sit’ |

|

|

mie ‘nimble’ |

hxa nie ‘tongue’ |

nyiet ‘late’ |

ngie ‘turn over’ |

|

mat (illocut. part.) |

na ‘ill; ache’ |

|

nga ‘I’ |

|

muo (classifier) |

nuo ‘hide’ |

nyuo bby ‘tears’ |

nguo ‘chest’ |

|

mo ‘see’ |

not ‘flesh’ |

nyot ‘paste, stick’ |

ngo ‘cry’ |

|

|

ne ‘you’ |

|

nge ‘be’ |

|

mup ‘hemp’ |

nut ‘sunken’ |

nyu ‘crawl’ |

|

|

m |

hm |

n |

hn |

|---|---|---|---|

|

mix ‘even’ |

hmi ‘name’ |

ni ‘sprout’ |

ax hni ‘red’ |

|

miep ‘front’ |

hmie ‘poke, flick’ |

niep sha ‘Liángshān’ |

xyx hnie ‘shoe’ |

|

ma (classifier) |

hmat ‘teach’ |

nax li ‘chronic ill’ |

hna ‘ask’ |

|

iet muop ‘dream’ |

|

ax nuo ‘hide’ |

|

|

mot ‘soldier’ |

hmo ‘blow’ |

nop ‘you’ (pl.) |

hnop ‘drive’ |

|

mu ‘do, make’ |

hmu ‘mushroom’ |

ix nu ‘soft’ |

a hnut ‘deep’ |

|

mur hni ‘siblings’ |

hmur ‘explode’ |

nur ji ‘soybean pod’ |

|

|

n |

l |

hn |

hl |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ni ‘scent’ |

li ‘go upwards’ |

hnip ‘smell’ |

hlit ‘dry in sun’ |

|

niep ga ‘pumpkin’ |

lie ‘scald’ |

hniet rra ‘vegetable’ |

hlie ‘spleen’ |

|

na shy ‘typhus’ |

la ‘come’ |

hna ‘listen’ |

hla ‘soul’ |

|

nuo su ‘Nuosu’ |

luo ‘instance’ |

|

hluo ‘rinse’ |

|

no ‘equal’ |

lo ‘boat’ |

hnox ‘until’ |

hlo ‘entertain’ |

|

ne ‘stop’ |

le ‘ox’ |

nep ndit ‘lack’ |

hlep ‘month’ |

|

nu ‘leprosy’ |

lu ‘dragon’ |

hnut kip ‘deep soil’ |

hlu ‘stir fry’ |

|

nur ni ‘sprout’ |

lur kur ‘city’ |

|

hlur ‘fester’ |

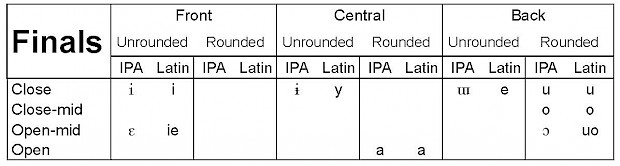

2. Vowels: Nuosu exhibits eight vocalic phonemes: two front vowels, two central vowels, and four back vowels. They have been depicted in Nuosu Pinyin and IPA below.

|

i |

ie |

y |

e |

|---|---|---|---|

|

i (logophor) |

ie ‘duck’ |

|

e ‘yes’ (agreement) |

|

ddip ‘be called’ |

ddie ‘serve as’ |

|

dde (nominalizer) |

|

gi ‘official’ |

gie ‘strange’ |

|

get ‘groom hair’ |

|

vi mop ‘ax’ |

vie hlur ‘worried’ |

vy ‘millet’ |

|

|

sit ‘kill’ |

sie ‘touch, pat’ |

syp ‘know’ |

|

|

|

|

shyp ‘seven’ |

shep ‘search’ |

|

zzip ‘compete’ |

zzie ‘engrave’ |

zzyt mu ‘world’ |

zze ‘wear out’ |

|

|

|

zhyp ‘urge’ |

zhet ‘correct’ |

|

nit ‘shift blame’ |

niep nie ‘breast milk’ |

|

nep ‘germs’ |

|

lip ‘elephant’ |

lie ‘pop up’ |

ly ‘request’ |

lep ‘swing’ |

|

u |

o |

uo |

a |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

op ‘goose’ |

uox ba ‘frog’ |

ap (negator) |

|

bu (classifier) |

bop ‘show’ |

buo ‘colour-match’ |

bat zhu ‘small cup’ |

|

ddu (nominalizer) |

ddox mu ‘knife’ |

dduo zip ‘ladder’ |

ddap ‘or’ |

|

gut ‘support’ |

go (classifier) |

guo ‘too much’ |

gat ‘dress’ |

|

vu ‘intestines’ |

vot ‘pig’ |

|

vat ‘dollar’ |

|

sup ‘resemble’ |

sot ‘calculate’ |

suo ‘quietly’ |

sat ‘all; finish’ |

|

shu ‘make’ |

shot ‘shameful’ |

shuo ‘brush by’ |

shax tur ‘bullet’ |

|

zzup zzup ‘icicle’ |

|

|

zzat ‘stare at’ |

|

zhut nyot ‘curl up’ |

zhop ‘coax’ |

zhuop zy ‘table’ |

zhat ‘embroider’ |

|

jjut ‘medium’ |

jjop ‘cut’ |

jjuo ‘chop’ |

|

|

mup ‘hemp’ |

mo ‘plow’ |

muo (classifier) |

ma ‘bamboo’ |

|

nu ‘leprosy’ |

not ‘flesh’ |

nuo ‘peep’ |

na ddi ‘epidemic’ |

|

lut ‘enough’ |

lot ‘hand’ |

luop (expressive) |

lat ‘tea’ |

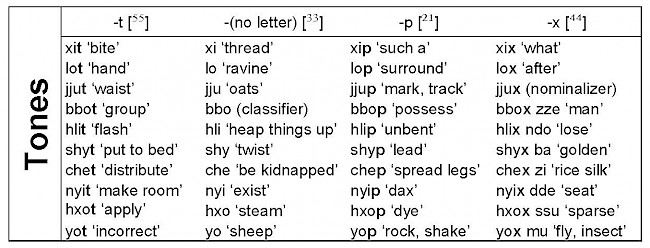

3. Tones: There are three tonemes, [55], [33], [21], in addition to a tone sandhi [44] whose phonological status is weak . This sandhi tone is primarily attested in disyllabic words. It is interesting to note that very few monosyllabic words carry this tone.

4. Syallabic Script: The different Yí groups share a long history of religious and secretive texts involving a syllabic script. The priests, who were the experts of the Yí writing, incorporated the use of similar character sets throughout the Yí residence area. Meanwhile the oldest traces of the Yí script go back to stone and pottery inscriptions, which, in turn, date back to the 8th century B.C.

Each grapheme of the Yí system corresponds to one syllable. After 1000 A.D., the priests conducted a writing reform by rotating the vertical orientation of characters into a horizontal one. For the most populous branch of Yí, the Nuosu of Liángshān prefecture, the Chinese Government standardized a set of 1119 characters in 1978. Specifically for this set, the orientation of graphemes was reverted to a vertical pattern similar to the one that was used in ancient times. The Nuosu system is used as a teaching medium in primary schools along with some secondary schools of Liángshān prefecture. Official documents are drafted in both Chinese and Nuosu. The International Standardization Organization (ISO) reserved space for the Nuosu character set in Unicode in 1995. With the Unicode support of Windows 2000, typewriting is possible through the use of special input software.

Nuosu syllables stand in one-to-one correspondence with graphemes of the script. There are 44 initial segments (43 consonants plus empty initial segment), ten final segments (eight plain vowels and two creaky vowels) and four suprasegments (three tonemes and one tone sandhi) of Nuosu. The theoretical number of logical syllables the script should provide graphemes for is 1,760. In wake of the fact that certain combinations of initials and finals are not attested in any dialect of Nuosu, the designers of the Government-sponsored Nuosu script standardized only 1,119 graphemes in 1978. An even smaller number of graphemes are in actual use in the standard Shynra dialect, about 1,005.

|

Type of Syllable |

Quantity |

|---|---|

|

Logical Syllables: |

1,760 (= 44 Initials ∙ 10 Finals ∙ 4 Suprasegments) |

|

Graphemes in Nuosu Script: |

1,119 |

|

Graphemes in actual use: |

1,005 |

Table 3: Use of Nuosu Graphemes

In the following Nuosu syllabary, the graphemes that are not in actual use are marked with gray shade.

Nuosu Syllabary ꆈꌠꁱꂷꋊꍬꄉꌠ

|

ꃚꌺ ꃚꃀ |

|

b |

p |

bb |

nb |

hm |

m |

f |

v |

d |

t |

dd |

nd |

hn |

n |

hl |

l |

g |

k |

gg |

mg |

hx |

ng |

h |

w |

z |

c |

zz |

nz |

s |

ss |

zh |

ch |

rr |

nr |

sh |

r |

j |

q |

jj |

nj |

ny |

x |

y |

ꃚꌐ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

i |

ꀀ ꀁ ꀂ ꀃ |

ꀖ ꀗ ꀘ ꀙ |

ꀸ ꀹ ꀺ ꀻ |

ꁖ ꁗ ꁘ ꁙ |

ꁶ ꁷ ꁸ ꁹ |

ꂑ ꂒ ꂓ ꂔ |

ꂮ ꂯ ꂰ ꂱ |

ꃍ ꃎ ꃏ ꃐ |

ꃢ ꃣ ꃤ ꃥ |

ꄀ ꄁ ꄂ ꄃ |

ꄚ ꄛ ꄜ ꄝ |

ꄶ ꄷ ꄸ ꄹ |

ꅑ ꅒ ꅓ ꅔ |

ꅨ ꅩ ꅪ ꅫ |

ꅽ ꅾ ꅿ ꆀ |

ꆗ ꆘ ꆙ ꆚ |

ꆷ ꆸ ꆹ ꆺ |

ꇚ ꇛ ꇜ ꇝ |

ꇸ ꇹ ꇺ ꇻ |

ꈔ ꈕ ꈖ

|

|

ꉆ ꉇ ꉈ ꉉ |

|

ꉮ

|

|

ꊍ ꊎ ꊏ ꊐ |

ꊮ ꊯ ꊰ ꊱ |

ꋐ ꋑ ꋒ ꋓ |

ꋭ ꋮ ꋯ ꋰ |

ꌉ ꌊ ꌋ ꌌ |

ꌪ ꌫ ꌬ ꌭ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ꏠ ꏡ ꏢ ꏣ |

ꏼ ꏽ ꏾ ꏿ |

ꐘ ꐙ ꐚ ꐛ |

ꐱ ꐲ ꐳ ꐴ |

ꑊ ꑋ ꑌ ꑍ |

ꑝ ꑞ ꑟ ꑠ |

ꑱ ꑲ ꑳ ꑴ |

t x

p |

|

ie |

ꀄ ꀅ ꀆ ꀇ |

ꀚ ꀛ ꀜ ꀝ |

ꀼ ꀽ ꀾ |

ꁚ ꁛ ꁜ ꁝ |

ꁺ ꁻ ꁼ |

ꂕ ꂖ ꂗ |

ꂲ ꂳ ꂴ |

|

ꃦ ꃧ ꃨ ꃩ |

ꄄ ꄅ ꄆ |

ꄞ ꄟ ꄠ |

ꄺ ꄻ ꄼ |

ꅕ ꅖ

|

ꅬ ꅭ ꅮ ꅯ |

ꆁ ꆂ ꆃ |

ꆛ ꆜ ꆝ |

ꆻ ꆼ ꆽ ꆾ |

ꇞ ꇟ ꇠ ꇡ |

ꇼ ꇽ ꇾ |

ꈗ ꈘ ꈙ |

ꈰ ꈱ

|

ꉊ ꉋ ꉌ ꉍ |

ꉝ ꉞ ꉟ |

ꉯ ꉰ

|

|

ꊑ ꊒ ꊓ |

ꊲ ꊳ ꊴ ꊵ |

ꋔ ꋕ ꋖ ꋗ |

ꋱ ꋲ ꋳ |

ꌍ ꌎ ꌏ |

ꌮ ꌯ ꌰ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ꏤ ꏥ ꏦ ꏧ |

ꐀ ꐁ ꐂ ꐃ |

ꐜ ꐝ ꐞ ꐟ |

ꐵ ꐶ ꐷ ꐸ |

ꑎ ꑏ ꑐ ꑑ |

ꑡ ꑢ ꑣ ꑤ |

ꑵ ꑶ ꑷ ꑸ |

t x

p |

|

a |

ꀈ ꀉ ꀊ ꀋ |

ꀞ ꀟ ꀠ ꀡ |

ꀿ ꁀ ꁁ ꁂ |

ꁞ ꁟ ꁠ ꁡ |

ꁽ ꁾ ꁿ ꂀ |

ꂘ ꂙ ꂚ ꂛ |

ꂵ ꂶ ꂷ ꂸ |

ꃑ ꃒ ꃓ ꃔ |

ꃪ ꃫ ꃬ ꃭ |

ꄇ ꄈ ꄉ ꄊ |

ꄡ ꄢ ꄣ ꄤ |

ꄽ ꄾ ꄿ ꅀ |

ꅗ ꅘ ꅙ ꅚ |

ꅰ ꅱ ꅲ ꅳ |

ꆄ ꆅ ꆆ |

ꆞ ꆟ ꆠ ꆡ |

ꆿ ꇀ ꇁ ꇂ |

ꇢ ꇣ ꇤ ꇥ |

ꇿ ꈀ ꈁ ꈂ |

ꈚ ꈛ ꈜ ꈝ |

ꈲ ꈳ ꈴ ꈵ |

ꉎ ꉏ ꉐ ꉑ |

ꉠ ꉡ ꉢ ꉣ |

ꉱ ꉲ ꉳ ꉴ |

ꊀ ꊁ ꊂ ꊃ |

ꊔ ꊕ ꊖ ꊗ |

ꊶ ꊷ ꊸ ꊹ |

ꋘ ꋙ ꋚ ꋛ |

ꋴ ꋵ ꋶ ꋷ |

ꌐ ꌑ ꌒ ꌓ |

ꌱ ꌲ ꌳ ꌴ |

ꍆ ꍇ ꍈ ꍉ |

ꍡ ꍢ ꍣ ꍤ |

ꍼ ꍽ

|

ꎔ ꎕ ꎖ ꎗ |

ꎫ ꎬ ꎭ ꎮ |

ꏆ ꏇ ꏈ ꏉ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t x

p |

|

uo |

ꀌ ꀍ ꀎ |

ꀢ ꀣ ꀤ |

ꁃ ꁄ ꁅ |

ꁢ ꁣ ꁤ |

|

ꂜ ꂝ ꂞ |

ꂹ ꂺ ꂻ ꂼ |

|

|

ꄋ ꄌ

|

ꄥ ꄦ ꄧ ꄨ |

ꅁ ꅂ ꅃ |

|

ꅴ ꅵ

|

ꆇ ꆈ ꆉ |

ꆢ ꆣ ꆤ |

ꇃ ꇄ ꇅ ꇆ |

ꇦ ꇧ ꇨ ꇩ |

ꈃ ꈄ ꈅ |

ꈞ ꈟ ꈠ ꈡ |

ꈶ ꈷ ꈸ |

ꉒ ꉓ ꉔ ꉕ |

ꉤ ꉥ ꉦ

|

ꉵ ꉶ ꉷ ꉸ |

ꊄ ꊅ ꊆ |

ꊘ ꊙ ꊚ |

ꊺ ꊻ ꊼ |

|

ꋸ ꋹ

|

ꌔ ꌕ ꌖ |

|

ꍊ ꍋ ꍌ |

ꍥ ꍦ ꍧ ꍨ |

ꍾ ꍿ

|

|

ꎯ ꎰ ꎱ |

ꏊ ꏋ ꏌ |

ꏨ ꏩ ꏪ ꏫ |

ꐄ ꐅ ꐆ ꐇ |

ꐠ ꐡ ꐢ |

ꐹ ꐺ

|

ꑒ ꑓ ꑔ |

ꑥ ꑦ

|

ꑹ ꑺ ꑻ ꑼ |

t x

p |

|

o |

ꀏ ꀐ ꀑ ꀒ |

ꀥ ꀦ ꀧ ꀨ |

ꁆ ꁇ ꁈ ꁉ |

ꁥ ꁦ ꁧ ꁨ |

ꂁ ꂂ ꂃ ꂄ |

ꂟ ꂠ ꂡ ꂢ |

ꂽ ꂾ ꂿ ꃀ |

ꃕ ꃖ ꃗ |

ꃮ ꃯ ꃰ ꃱ |

ꄍ ꄎ ꄏ ꄐ |

ꄩ ꄪ ꄫ ꄬ |

ꅄ ꅅ ꅆ ꅇ |

ꅛ ꅜ ꅝ ꅞ |

ꅶ ꅷ

ꅸ |

ꆊ ꆋ ꆌ ꆍ |

ꆥ ꆦ ꆧ |

ꇇ ꇈ ꇉ ꇊ |

ꇪ ꇫ ꇬ ꇭ |

ꈆ ꈇ ꈈ ꈉ |

ꈢ ꈣ ꈤ ꈥ |

ꈹ ꈺ ꈻ ꈼ |

ꉖ ꉗ ꉘ ꉙ |

ꉧ ꉨ ꉩ ꉪ |

ꉹ ꉺ ꉻ ꉼ |

ꊇ ꊈ ꊉ |

ꊛ ꊜ ꊝ ꊞ |

ꊽ ꊾ ꊿ ꋀ |

ꋜ ꋝ ꋞ |

ꋺ

ꋻ |

ꌗ ꌘ ꌘ ꌚ |

ꌵ ꌶ ꌷ ꌸ |

ꍍ ꍎ ꍏ ꍐ |

ꍩ ꍪ ꍫ ꍬ |

ꎀ ꎁ ꎂ ꎃ |

ꎘ ꎙ ꎚ |

ꎲ ꎳ ꎴ ꎵ |

ꏍ ꏎ ꏏ ꏐ |

ꏬ ꏭ ꏮ ꏯ |

ꐈ ꐉ ꐊ ꐋ |

ꐣ ꐤ ꐥ ꐦ |

ꐻ ꐼ ꐽ ꐾ |

ꑕ ꑖ ꑗ ꑘ |

ꑧ ꑨ ꑩ ꑪ |

ꑽ ꑾ ꑿ ꒀ |

t x

p |

|

e |

ꀓ ꀔ

|

ꀩ ꀪ ꀫ |

|

ꁩ ꁪ ꁫ |

|

|

ꃁ ꃂ

|

|

ꃲ

ꃳ |

ꄑ ꄒ ꄓ |

ꄭ ꄮ ꄯ |

ꅈ ꅉ ꅊ |

ꅟ ꅠ ꅡ |

ꅹ ꅺ ꅻ |

ꆎ ꆏ ꆐ |

ꆨ ꆩ ꆪ |

ꇋ ꇌ ꇍ |

ꇮ ꇯ ꇰ ꇱ |

ꈊ ꈋ ꈌ ꈍ |

ꈦ ꈧ ꈨ ꈩ |

ꈽ ꈾ ꈿ |

ꉚ ꉛ ꉜ |

ꉫ ꉬ ꉭ |

ꉽ ꉾ ꉿ |

ꊊ ꊋ ꊌ |

ꊟ ꊠ ꊡ |

ꋁ ꋂ ꋃ |

ꋟ ꋠ ꋡ |

ꋼ ꋽ

|

ꌛ ꌜ ꌝ |

ꌹ ꌺ ꌻ |

ꍑ ꍒ ꍓ ꍔ |

ꍭ ꍮ ꍯ ꍰ |

ꎄ ꎅ ꎆ ꎇ |

ꎛ ꎜ ꎝ ꎞ |

ꎶ ꎷ ꎸ ꎹ |

ꏑ ꏒ ꏓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t x

p |

|

u |

|

ꀬ ꀭ ꀮ ꀯ |

ꁊ ꁋ ꁌ ꁍ |

ꁬ ꁭ ꁮ ꁯ |

ꂅ ꂆ ꂇ ꂈ |

ꂣ ꂤ ꂥ ꂦ |

ꃃ ꃄ ꃅ ꃆ |

ꃘ ꃙ ꃚ ꃛ |

ꃴ ꃵ ꃶ ꃷ |

ꄔ ꄕ ꄖ ꄗ |

ꄰ ꄱ ꄲ ꄳ |

ꅋ ꅌ ꅍ ꅎ |

ꅢ ꅣ ꅤ ꅥ |

ꅼ

|

ꆑ ꆒ ꆓ ꆔ |

ꆫ ꆬ ꆭ ꆮ |

ꇎ ꇏ ꇐ ꇑ |

ꇲ ꇳ ꇴ ꇵ |

ꈎ ꈏ ꈐ ꈑ |

ꈪ ꈫ ꈬ ꈭ |

ꉀ ꉁ ꉂ ꉃ |

|

|

|

|

ꊢ ꊣ ꊤ ꊥ |

ꋄ ꋅ ꋆ ꋇ |

ꋢ ꋣ ꋤ |

ꋾ ꋿ ꌀ |

ꌞ ꌟ ꌠ ꌡ |

ꌼ ꌽ ꌾ ꌿ |

ꍕ ꍖ ꍗ ꍘ |

ꍱ ꍲ ꍳ |

ꎈ ꎉ ꎊ ꎋ |

ꎟ ꎠ ꎡ ꎢ |

ꎺ ꎻ ꎼ ꎽ |

ꏔ ꏕ ꏖ ꏗ |

ꏰ ꏱ ꏲ ꏳ |

ꐌ ꐍ ꐎ ꐏ |

ꐧ ꐨ ꐩ ꐪ |

ꐿ ꑀ ꑁ |

ꑙ ꑚ ꑛ ꑜ |

|

ꒁ ꒂ ꒃ ꒄ |

t x

p |

|

ur |

|

ꀰ ꀱ |

ꁎ ꁏ |

ꁰ ꁱ |

ꂉ ꂊ |

ꂧ ꂨ |

ꃇ ꃈ |

ꃜ ꃝ |

ꃸ ꃹ |

ꄘ ꄙ |

ꄴ ꄵ |

ꅏ ꅐ |

ꅦ ꅧ |

|

ꆕ ꆖ |

ꆯ ꆰ |

ꇒ ꇓ |

ꇶ ꇷ |

ꈒ ꈓ |

ꈮ ꈯ |

ꉄ ꉅ |

|

|

|

|

ꊦ ꊧ |

ꋈ ꋉ |

ꋥ ꋦ |

ꌁ ꌂ |

ꌢ ꌣ |

|

ꍙ ꍚ |

ꍴ ꍵ |

ꎌ ꎍ |

ꎣ ꎤ |

ꎾ ꎿ |

ꏘ ꏙ |

ꏴ ꏵ |

ꐐ ꐑ |

ꐫ ꐬ |

ꑂ ꑃ |

|

|

ꒅ ꒆ |

x

|

|

y |

|

ꀲ ꀳ ꀴ ꀵ |

ꁐ ꁑ ꁒ ꁓ |

ꁲ ꁳ ꁴ ꁵ |

ꂋ ꂌ ꂍ ꂎ |

ꂩ ꂪ ꂫ |

ꃉ ꃊ ꃋ ꃌ |

ꃞ ꃟ ꃠ ꃡ |

ꃺ ꃻ ꃼ ꃽ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ꆱ ꆲ ꆳ ꆴ |

ꇔ ꇕ ꇖ ꇗ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ꊨ ꊩ ꊪ ꊫ |

ꋊ ꋋ ꋌ ꋍ |

ꋧ ꋨ ꋩ ꋪ |

ꌃ ꌄ ꌅ ꌆ |

ꌤ ꌥ ꌦ ꌧ |

ꍀ ꍁ ꍂ ꍃ |

ꍛ ꍜ ꍝ ꍞ |

ꍶ ꍷ ꍸ ꍹ |

ꎎ ꎏ ꎐ ꎑ |

ꎥ ꎦ ꎧ ꎨ |

ꏀ ꏁ ꏂ ꏃ |

ꏚ ꏛ ꏜ ꏝ |

ꏶ ꏷ ꏸ ꏹ |

ꐒ ꐓ ꐔ ꐕ |

ꐭ ꐮ ꐯ ꐰ |

ꑄ ꑅ ꑆ ꑇ |

|

ꑫ ꑬ ꑭ ꑮ |

ꒇ ꒈ ꒉ ꒊ |

t x

p |

|

yr |

|

ꀶ ꀷ |

ꁔ ꁕ |

|

ꂏ ꂐ |

ꂬ ꂭ |

|

|

ꃾ ꃿ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ꆵ ꆶ |

ꇘ ꇙ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ꊬ ꊭ |

ꋎ ꋏ |

ꋫ ꋬ |

ꌇ ꌈ |

ꌨ ꌩ |

ꍄ ꍅ |

ꍟ ꍠ |

ꍺ ꍻ |

ꎒ ꎓ |

ꎩ ꎪ |

ꏄ ꏅ |

ꏞ ꏟ |

ꏺ ꏻ |

ꐖ ꐗ |

|

ꑈ ꑉ |

|

ꑯ ꑰ |

ꒋ ꒌ |

x

|

References

The information presented on this page originates from (Gerner 2013; 2015).

Anonymous (2000). Change among the Nuosu. MA Thesis.

Baber, E. C. (1882). Travels and researches in Western China. London: Royal Geographical Society Supplementary Papers.

Bradley, D. (2001). Language policy for the Yí. In S. Harrell (ed.), Perspectives on the Yi of Southwest China, 195-213. Berkeley: University of California.

Chén Guóguāng 陈国光 (2003). Hindu Caste System and Yí Caste System 印度种姓制度与凉山彝族等级制, Bulletin of the Central University of Nationalities, Issue 3, 《中央民族大学学报》,2003 年第 3 期。

Chén Shìlín 陈士林 (1985). A Sketch of the Yí language 彝语简志. Běijīng 北京: Nationality Press 民族出版社.

Covell, R. (1990). Mission Impossible. The unreached Nosu on China’s Frontier. Pasadena: Hope Publishing House.

Crabouillet, F. L. (1873). “Les Lolos”. Les Missions Catholiques, Tome V, pp. 71-72, 93-94, 105-107. Lyon.

Gerner, M. (2013). The Grammar of Nuosu. MGL 64. Berlin: Mouton.

Gerner, M. (2015). “Yí 彝.” Encyclopedia of Chinese language and linguistics. General Editor Sybesma, R. Leiden: Brill Online.

Harrel, S. (2001). Ways of being ethnic in Southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Hú Sùhuá 胡素华 (2002). Research on structural particles in the Yí language 彝语结构助词研究. Běijīng 北京: Nationality Press 民族出版社.

Jiǎng Yìwén 蒋益文 (2010). Bits on the History of the Yí nationality 彝族历史点滴. Bulletin of Chinese Nationalities, 15th of October, 2010 《中国民族报》 2010 年 10 月 15 日.

Kupfer, K. (2001). ‘Geheimgesellschaften’ in der VR China: Christlich inspirierte, spirituell-religöse Gruppierungen seit 1978. China Analysis No. 8. Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies. University of Trier, Germany.

Mǎ Chángshòu 马长寿 (1985). The Ancient History of the Yí people 彝族古代史,edited by Lǐ Shàomíng 李绍明(主编). Shànghǎi 上海: Shànghǎi People’s Publishing House 上海人民出版社.

Mǎ Línyīng 马林英, D. E. Walters and S. Walters (2008). Yí-Chinese-English Common Vocabulary 彝汉英常用词词汇. Běijīng 北京: Nationality Press 民族出版社.

Moule, A.C and Pelliot, P. (1938). Marco Polo: The Description of the World. Translated and edited. London: George Routledge and Sons.

Pollard, W. (1928). The life of Sam Pollard of China. London: Seeley.

Zhū Jiànjūn 朱建军 (2007). Bits of Knowledge about Problems of the Yí Script 对彝文发生问题的几点认识. Bulletin of Nèijiāng Teacher's College, Issue 3 《内江师范学院学报》, 2007 年第 3 期.