Introduction

The Neasu people reside in Guìzhōu province and speak a language related to the Nuosu language in Sìchuān province. The difference between Nuosu and Neasu can be compared with the distance between Mandarin Chinese and Cantonese (or between English and Dutch).

Neasu in the Burmish-Lolo GroupTwo ethno-linguistic Yí (彝)The Yí (彝) nationality is one China’s official 56 nationalities. groups, the Neasu and Nyisu, speaking two almost unintelligible languages, populate Bìjié 毕节 prefecture of Guìzhōu province. Despite some overlaps, the Neasu are concentrated in Western and Southern Bìjié: in Wēiníng 威宁, Hèzhāng 赫章, Nàyōng 纳雍 and Zhījīn 织金 counties (also in Shuǐchéng 水城 county of Liùpánshuǐ 六盘水 prefecture). On the other hand, the Nyisu live in North-Eastern Bìjié: in Dàfāng 大方, Qiánxī 黔西 and Jīnshā 金沙 counties. As ethnic groupsSome of these Neasu and Nyisu do not speak their ancestral language, but only the local Chinese dialect., the population of Neasu and Nyisu is about 600,000 and 500, 000, respectively.

Neasu in the Burmish-Lolo GroupTwo ethno-linguistic Yí (彝)The Yí (彝) nationality is one China’s official 56 nationalities. groups, the Neasu and Nyisu, speaking two almost unintelligible languages, populate Bìjié 毕节 prefecture of Guìzhōu province. Despite some overlaps, the Neasu are concentrated in Western and Southern Bìjié: in Wēiníng 威宁, Hèzhāng 赫章, Nàyōng 纳雍 and Zhījīn 织金 counties (also in Shuǐchéng 水城 county of Liùpánshuǐ 六盘水 prefecture). On the other hand, the Nyisu live in North-Eastern Bìjié: in Dàfāng 大方, Qiánxī 黔西 and Jīnshā 金沙 counties. As ethnic groupsSome of these Neasu and Nyisu do not speak their ancestral language, but only the local Chinese dialect., the population of Neasu and Nyisu is about 600,000 and 500, 000, respectively.

In the Western language nomenclature (ISO 639-3), the Yí people of North-eastern Yúnnán and Northwestern Guìzhōu are referred to as Wūsǎ Yí 乌撒彝The ISO 639-3 code for this language is given as “yig”. and Wūmēng Yí 乌蒙彝The ISO 639-3 code for this language is given as “ywu”. with some ambiguity pertaining to their delimitation and origin. Wūsǎ 乌撒 and Wūmēng 乌蒙 are the names of former administrative districts that are mentioned in the “History of the Yuán DynastyThe “History of Yuán” or 《元史》 is the official Chinese historiography of the Mongol dynasty (1271-1368) posthumously commissioned by the Míng court and compiled in 1370 under the direction of Sòng Lián 宋濂. “The History of Yuán” is part of the “Twenty-Four Histories” 《二十四史》, a collection of historiographies spanning over a period between 91BC and 1739. The 《元史》 includes biographies (本纪) of 47 Mongol emperors and Khans; biographies (列傳) of 97 non-imperial people; 58 treaties (志) on geographic, socio-economic, historical and legal issues; 8 chronological tables. In the section “Geographic Treaties” 《地理志》, the districts Wūsǎ 乌撒 and Wūmēng 乌蒙 are mentioned.

See Lǐ Zhì'ān 李治安 and Xuē Lěi 薛磊, 2009, Comprehensive History of the administrative subdivisions of China, Volume of the Mongol Dynasty 《中国行政区划通史·元代卷》. Shànghǎi 上海: Fùdàn University Press 复旦大学出版社.”. The Chinese historiographer Mă Chángshoù 马长寿 identifies Wūsǎ and WūmēngSee Mă Chángshoù 马长寿, 1985, The Ancient history of the Yí 《彝族古代史》, p.65, edited by Lĭ Shàomíng 李绍明 (主编). Shànghăi 上海: Shànghăi People’s Press 上海人民出版社. with the modern day cities of Wēiníng 威宁 in Guìzhōu and Zhāotōng 昭通 in Yúnnán. (Today Wūmēng is the name of a mountain range in the Zhāotōng region.) The exact extent of Wūsǎ and Wūmēng, however, is unknown. Small pockets of Nasu speakers continue to exist in the modern-day area of Zhāotōng, but their speech is largely unintelligible to both Neasu and Nyisu speakers. Consequently, associating Wūmēng Yí and Wūsǎ Yí with Neasu and Nyisu is an erroneous approach. Rather, Wūmēng Yí refers to scattered pockets of Yí people within the Zhāotōng prefecture (Yúnnán province) and Wūsǎ Yí to Yí people in Western Guìzhōu province.

Culture

(A) History: The exact time of when the ancestors of the Neasu and Nyisu people started to populate Western Guìzhōu is unknown but predates the edition of the “Book of the Southern BarbariansThe “Book of the Southern Barbarians” or 《蛮书》 was the work of Fán Chuò 樊绰 , a secretary of Cài Xí 蔡袭, the Chinese Governor of Tongkin during the Táng 唐 dynasty (Tongkin is a westernized form of Đông Kinh 东京, the former name of Hanoi in Vietnam). Fán Chuò published his work during 860-865 in which he compiles the ethnic groups of Yúnnán and neighboring areas of that time. The oldest preserved Chinese manuscript of Book of the Southern Barbarians 《蛮书》 is an edition written at the Wǔyīng Hall 武英殿 in the Forbidden City of Běijīng in 1774 (Pelliot 1904: 132). Gordon Luce translated the 《蛮书》 into English in 1961 (Luce 1961).

See Pelliot, P., 1904, Deux itinéraires de Chine en Inde à la fin du VIIIe siècle, Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient 4, 131-413.

Luce, G. H., 1961, Book of the Southern Barbarians 《蛮书》. English Translation. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University.” which was published in 860-874. This book makes reference to the Cuàn 爨 kingdom (ca. 323-738), also distinguishing between the Wūmán 乌蛮 (Black Barbarians) and Báimán 白蛮 (White Barbarians). The Cuàn kingdom was centered in the southeast of Kunming and disintegrated in the 8th century in order to make place for the Nánzhào 南诏 kingdom (738-937). Subjugated to the Nánzhào kingdom, the Cuàn polity morphed into two wings: Western and Eastern Cuàn, the latter extending into Guìzhōu province and covering the majority of contemporary Neasu and Nyisu areas. The Book of the Southern Barbarians associates the Wūmán with Eastern Cuàn and the Báimán with Western CuànSee Luce, G. H., 1961, Book of the Southern Barbarians 《蛮书》. English Translation. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University.. Since the Wūmán and Báimán were both known to be slave societiesThe color term ‘black’ denotes the class of ethnic aristocrats and ‘white’ to the caste of ordinary free men. just as the latter Yí were, some scholarsWhile Mă Chángshoù 马长寿 (1985: 69-73) is undecided, Steven Harrell (1995: 87) believes that the Eastern Cuàn were Yí and the Western Cuàn might have included Yí as well as other groups such as the Bái 白 people.

See Mă Chángshoù 马长寿, 1985, The Ancient history of the Yí 《彝族古代史》, edited by Lĭ Shàomíng 李绍明 (主编). Shànghăi 上海: Shànghăi People’s Press 上海人民出版社.

Harrell, S., 1995, The history of the history of the Yi, in S. Harrell (ed.), Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers, 63-91. Seattle: University of Washington Press. suggested the Wūmán and Báimán to be the ancestors of the Yí.

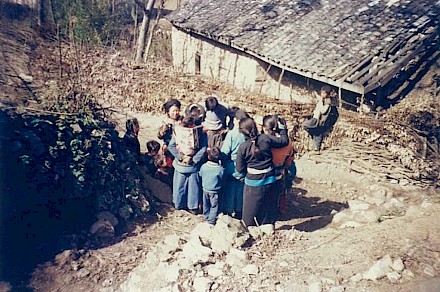

Neasu women at Cǎohǎi Lake 草海Cǎohǎi Lake 草海 is located in Wēiníng 威宁 county of Western Guìzhōu.Another indication of an ancient origin of the Yí in Western Guìzhōu comes from their native myths, the so-called Yí ClassicsAcross four provinces of Southwest China, the Shamans of the Yí folk religion(s) had used similar pictographic scripts to transmit their knowledge from one generation to the other. Chinese scholars (notably Yáng Chéngzhì 杨成志, Mǎ Xuéliáng 马学良 and Dīng Wénjiāng 丁文江) started to take interest and to collect manuscripts from the Yí Shamans in the 1920s. Some of these manuscripts can be traced back to the 17th century and earlier. In the 1970s, the Chinese Government funded a translation project where elderly Shamans from Yúnnán, Sìchuān, Guìzhōu and Guǎngxī provinces were invited to translate the collected manuscripts into Chinese. Similar projects continued at a provincial level until the late 1990s. The translated manuscripts can be classified under eight topics: (1) creation myths; (2) flood myths; (3) six ancestors myths; (4) myths on the origin of the script; (5) religious practices of Shamans; (6) texts for guiding the deceased soul to its ancestral place (指路经); (7) texts to describe the black/white color symbolism (Wu 1998). One important subset of documents is the “Southwest Yí Chronicles” 《西南彝志》 which was edited and published in Guìzhōu during 1989-1994. The chronicles describe the geographical distribution of the different Yí tribes. See

Neasu women at Cǎohǎi Lake 草海Cǎohǎi Lake 草海 is located in Wēiníng 威宁 county of Western Guìzhōu.Another indication of an ancient origin of the Yí in Western Guìzhōu comes from their native myths, the so-called Yí ClassicsAcross four provinces of Southwest China, the Shamans of the Yí folk religion(s) had used similar pictographic scripts to transmit their knowledge from one generation to the other. Chinese scholars (notably Yáng Chéngzhì 杨成志, Mǎ Xuéliáng 马学良 and Dīng Wénjiāng 丁文江) started to take interest and to collect manuscripts from the Yí Shamans in the 1920s. Some of these manuscripts can be traced back to the 17th century and earlier. In the 1970s, the Chinese Government funded a translation project where elderly Shamans from Yúnnán, Sìchuān, Guìzhōu and Guǎngxī provinces were invited to translate the collected manuscripts into Chinese. Similar projects continued at a provincial level until the late 1990s. The translated manuscripts can be classified under eight topics: (1) creation myths; (2) flood myths; (3) six ancestors myths; (4) myths on the origin of the script; (5) religious practices of Shamans; (6) texts for guiding the deceased soul to its ancestral place (指路经); (7) texts to describe the black/white color symbolism (Wu 1998). One important subset of documents is the “Southwest Yí Chronicles” 《西南彝志》 which was edited and published in Guìzhōu during 1989-1994. The chronicles describe the geographical distribution of the different Yí tribes. See

Wu Ga, 1998, “Discovering and re-discovering Yi identity: Shared identity narratives from the classics of Yúnnán, Sìchuān, Guìzhōu and Guǎngxī”, paper presented at the Second International Conference on Yi-studies, held at the University of Trier, Germany, 19th to 23rd of June, 1998.

Guìzhōu Bìjié Yí Translation Committee 贵州毕节地区彝文翻译组, 1989-1994, Southwest Yí Chronicles 《西南彝志》, Volume 1-8 一至八卷, Bìjié Nationality Affairs Committee 毕节地区民族事务委员会. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社.. As per one transregional myth, there was a universal flood with one male survivor who became the progenitor of the human race. His name is variously recorded as Apudumo or Zzemuvyvy, Zomu, Jumu, Zhomuyou, Zhongmuyou (transliterated in Chinese as 仲牟由) etc. Together with three heavenly wives, he begot six sonsSix direct sons or six descendants with intermediate generations.: Wǔ 武, Zhà 乍, Nuò 糯, Héng 恒, Bù 布, and Mò 默. They founded six clans who later moved into six cardinal directions: “Centre”, “North”, “West”, “South”, “East”, “South”, and “Southeast”. Chinese historiansSee Luó Guóyì 罗国义 and Chén Yīng 陈英, 1984, Selected Classics related to the Six Ancestors 《彝族六祖典籍选编》. Běijīng 北京: Central University of Nationalities Press 中央民族大学出版社. have linked the migration of the six clans to the centrifugal forces of the Cuàn 爨 kingdom (ca. 323-738) at the end of its reign. Today, Chinese linguistsFor example, see Chén Shìlín 陈士林, 1985, A Sketch of the Yí language 《彝语简志》. Běijīng 北京: Nationality Press 民族出版社。 classify the Yí languages into six subgroupsAccording to the communist policy principle, the Yí are understood as one nationality speaking one language. These linguistic differences are called “north Yí dialect”, “central Yí dialect”, “west Yí dialect”, “south Yí dialect”, “southeast Yí dialect” and “east Yí dialect”. The Neasu and Nyisu languages belong to or are the “east Yí dialect”. based on this myth. David BradleySee Bradley, D., 2001, “Language policy for the Yi”, in S. Harrell, ed., Perspectives on the Yi of Southwest China, pp. 195-213 (particularly 201-202). Berkeley: University of California Press. is also known to credit to the idea of the six clans and their migration pattern. According to the “Southwest Yí ChroniclesSee previous note. The “Southwest Yí Chronicles” 《西南彝志》 describe the geographical distribution of the different Yí tribes.” or 《西南彝志》, two clans, the Bù and Mò, moved to Guìzhōu, fought wars and settled there. To the extent that the connection of the ancestors of the Neasu and Nyisu to the Cuàn kingdom remains valid, their settlement in Western Guìzhōu must be ancient and have probably occurred during the later Hàn dynasty (25-220).

In the paradigm of communist historiographyThe communist view of history was laid out by Lewis Henry Morgan (1985)/(1877) and Friedrich Engels (1884) and breaks down the history of a people into five evolutionary stages defined in relation to production: the primitive (first matrilineal then patrilineal), slave, feudal, capitalist and socialist modes of production. This theory was particularly adopted in the Soviet Union and in the People’s Republic of China. Mă Chángshoù’s work “The ancient history of the Yí” is organized into these five stages and serves as a good example of how the theory is put to work. See Harrell (1995:84-89) for an evaluation of Mă ‘s historiography. See

Mă Chángshoù 马长寿, 1985, The Ancient history of the Yí 《彝族古代史》, edited by Lĭ Shàomíng 李绍明 (主编). Shànghăi 上海: Shànghăi People’s Press 上海人民出版社.

Harrell, S. (1995). The history of the history of the Yi, in S. Harrell (ed.), Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers, 63-91. Seattle: University of Washington Press., Chinese scholarsSee for example Wu Ga, 1998, “Discovering and re-discovering Yi identity: Shared identity narratives from the classics of Yúnnán, Sìchuān, Guìzhōu and Guǎngxī”, paper presented at the Second International Conference on Yi-studies, held at the University of Trier, Germany, 19th to 23rd of June, 1998, p.19. believe that at the time of the formation of the six clans, the Yí society remained in a primitive stage and was yet to develop social classes. In line with the predictions made by Friedrich Engels (1884), slavery was introduced when the clans fought among themselves and also engaged in warfare with other tribes. The Wǔ clan in Yúnnán and the Mò clan in Guìzhōu were particularly involved in fighting and in making captives whom they enslavedSee Mă (1985: 12-13).

Mă Chángshoù 马长寿, 1985, The Ancient history of the Yí 《彝族古代史》, edited by Lĭ Shàomíng 李绍明 (主编). Shànghăi 上海: Shànghăi People’s Press 上海人民出版社.. The establishment of slaves required a reorganization of the “free people” in social classes, in a class of aristocrats as well as a class of ordinary “free” people; the original color metaphor of Black Yí/Barbarians and White Yí/Barbarians applies to these social classes. Today, the use of this metaphor varies in Southwest China.

Cranes at Cǎohǎi Lake 草海Black-necked cranes 黑颈鹤 are a symbol of Cǎohǎi Lake 草海.In Sìchuān and to a lesser extent in Guìzhōu, the colors still reflect the former social classes, while in Yúnnán ‘black’ and ‘white’ have become traits of ethno-linguistic identityFor example, the Kopho of Lùquàn 禄劝 county consider themselves to be entirely composed of White Yí, while the Nasu people of Lùquàn county consist of Black Yí and speak a language that is almost unintelligible with Kopho.. Mă Chángshoù estimatesSee Mă (1985:39-49).

Cranes at Cǎohǎi Lake 草海Black-necked cranes 黑颈鹤 are a symbol of Cǎohǎi Lake 草海.In Sìchuān and to a lesser extent in Guìzhōu, the colors still reflect the former social classes, while in Yúnnán ‘black’ and ‘white’ have become traits of ethno-linguistic identityFor example, the Kopho of Lùquàn 禄劝 county consider themselves to be entirely composed of White Yí, while the Nasu people of Lùquàn county consist of Black Yí and speak a language that is almost unintelligible with Kopho.. Mă Chángshoù estimatesSee Mă (1985:39-49).

Mă Chángshoù 马长寿, 1985, The Ancient history of the Yí 《彝族古代史》, edited by Lĭ Shàomíng 李绍明 (主编). Shànghăi 上海: Shànghăi People’s Press 上海人民出版社. that the slave system and the social classes had been established across all the Yí areas by at least the Three Kingdoms 三国 (220-280) period. The slave system endured during the Nánzhào 南诏 (738-937) and Dàlǐ 大理 kingdoms (937-1253), but was gradually replaced by a feudal systemAccording to the classical definition of Ganshof (1944), feudalism describes the societal contract between a lord (主人) and a vassal (附庸) based on the idea of fief (领地). A fief is a heritable property or a right granted by the lord to the vassal in exchange for service, proceeds, or loyalty. See

Ganshof, F. L., 1982(1944). Qu'est-ce que la féodalité? Paris: Taillandier.. The transformation happened especially during the Dàlǐ kingdom under the influence of Hàn settlers who already operated under a feudal system at that time. When the Mongols established rule in China, Kublai Khan officially abolished slaverySee Mă (1985:96-97).

Mă Chángshoù 马长寿, 1985, The Ancient history of the Yí 《彝族古代史》, edited by Lĭ Shàomíng 李绍明 (主编). Shànghăi 上海: Shànghăi People’s Press 上海人民出版社. by a decree in 1283, tipping the balance in favor of feudalism in Southwest China. The Mongols also subsidized a ruling system that recognized the existing social structure. They established a small elite of indigenous chieftains known as Tŭsī 土司 who were taken from the class of Black Yí. The Míng and Qīng governments left the social classes of the Yí intact and continued using the system of ethnic Tŭsī.

During the transition from the Míng dynasty (1368-1644) to the Qīng dynasty (1644-1911), the Yí in Guìzhōu assumed the role of imperial enabler (or disabler)The Sìchuān Yí of the 20th century played a similar systemic role as the Guìzhōu Yí of the 17th century when their chieftains decided to allow the Communist Red Army pass through Liángshān on its Long March to power in April 1935. for a short period. Wú Sānguì 吴三桂 (1612-1678) was a general of the Míng court, who after the downfall of the Míng dynasty defected, surrendered to the Manchu rulers and was commissioned by the Qīng court to quell pockets of Míng resistance all over China. Wú garrisoned Northeastern Yúnnán during 1662-1668, and fought the Yí Tŭsī in Western Guìzhōu, who had remained loyal to the Míng rulers, before expulsing them. The Yí Tŭsī and their numerous followers fled from Western GuìzhōuSee the Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles, Wēiníng Mínwěi (1997:50-51).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社. to Liángshān 凉山 (in Sìchuān) and Hónghé 红河 (in Yúnnán). Their defeat contributed to the emergence of the Qīng dynasty.

The feudalization of society was most complete in Yúnnán where the (purported former) slave castes developed into independent ethno-linguistic groupsFor example, the Aluphu of Lùquàn 禄劝 county, called Dry Yí 干彝 in Chinese, are descendants of slaves. They have evolved as an independent Yí group.. In Sìchuān, slavery survived as the main organization principleSee Mă (1985: 106-108) and Harrell (1995: 88).

Mă Chángshoù 马长寿, 1985, The Ancient history of the Yí 《彝族古代史》, edited by Lĭ Shàomíng 李绍明 (主编). Shànghăi 上海: Shànghăi People’s Press 上海人民出版社.

Harrell, S., 1995, The history of the history of the Yi, in S. Harrell, ed., Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers, 63-91. Seattle: University of Washington Press. of the Nuosu society until 1956, when the communist government quashed a rebellion and assumed total control of the Nuosu society. The Yí society in Western Guìzhōu has been hybrid: slavery endured within a feudal society until the 20th century. The British missionary Samuel Pollard 柏格理 (1864-1915), who was stationed in Wēiníng (Guìzhōu), described the Neasu as a feudal society with slave castesSee Samuel Pollard (1921: 137-145).

See Pollard, W., 1928, The life of Sam Pollard of China. London: Seeley.. At the top were the Tŭsī or Neasu landowners whom Pollard nicknamed “Earth Eyes” and who had to pay taxes to the Chinese government. Within the society, the Neasu Tŭsī treated the Black NeasuPollard nicknamed them “Black Bloods”. as vassals to whom they let land and from whom they requested loyalty, military services, and availability. The Neasu landowners often engaged in skirmishes with other landowners. In such instances, the Black Neasu had to contribute their own men to the battle. The Black Neasu in turn assigned portions of their land to the White NeasuPollard called them “White Bloods”. in exchange for military service and proceeds. The White Neasu had to be available to the Black Neasu as fighters if a landlord would call on the Black Neasu as well as their subordinates for battle. All three layers of society, Neasu Tŭsī, Black Neasu and White Neasu, held slaves. One type of slaves lived in their own houses and was supposed to provide goods and services to their lords at all times. Furthermore, there were household slaves who lived in the same house as their masters and had to serve them at all times.

Neasu Widow of a rich TŭsīThe deceased Tŭsī owned thousands of acres. This picture was taken between 1904 and 1915 and was published in Walter Pollard (1928)’s book, p.184. Walter was the son of Samuel Pollard.

Neasu Widow of a rich TŭsīThe deceased Tŭsī owned thousands of acres. This picture was taken between 1904 and 1915 and was published in Walter Pollard (1928)’s book, p.184. Walter was the son of Samuel Pollard.

Black Neasu man with daughterThis picture was taken between 1904 and 1915 and was published in Walter Pollard (1928)’s book, p.184.

Black Neasu man with daughterThis picture was taken between 1904 and 1915 and was published in Walter Pollard (1928)’s book, p.184.

The Wēiníng Nationality ChroniclesSee Wēiníng Mínwěi (1997:51).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社. reported an incident that occurred in 1730. È'ěrtài 鄂尔泰, the Manchu governor of Southwest China, performed a land reform and dispossessed many Yí Tŭsī in Yúnnán and Guìzhōu. The Yí Tŭsī of Wūmēng (Zhāotōng) and Wūsǎ (Wēiníng) resisted, combined forces, and succeeded in smuggling weapons into the fortified city of Zhāotōng where imperial soldiers garrisoned. On a given day, they mounted a rebellion and were able to kill the Chinese military officer Liú Qǐyuán 刘起元. When a report of this rebellion reached the governor, an army of 10,000 soldiers was dispatched to Zhāotōng which put down the rebellion.

Slavery and fiefs were completely abolished during the communist era, but the Neasu and Nyisu remain conscious of the social classes. In their own language, they call the caste of former landowners (or Tŭsī) the Anzumo, Black Yí the Nasu, and White Yí the Tusu. Moreover, they remember two lower castes, the Lagea who are termed in Chinese as Red Yí 红彝 as well as the Go referred to as Dry Yí 干彝 in Chinese. The Lagea are the descendants of household slaves, while the Go are the descendants of the slaves residing in their own housesBefore the 1950s, the Go were known for their production of crafted bamboo utensils (Wēiníng Mínwěi 1997:30).

See Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社.. The distribution of the five castes in the Neasu and Nyisu groups differs and is depicted in the table below (with Nuosu in Sìchuān as an additional reference point). The majority of the Neasu belong to the Tusu caste, whereas the majority of the Nyisu are associated with the Nasu caste. The Lagea and Go castes have no known descendants in Neasu, but only in the Nyisu group.

|

Social Class |

Neasu (Guìzhōu) |

Nyisu (Guìzhōu) |

|---|---|---|

|

Anzumo 土司 |

ca. 1% |

ca. 1% |

|

Nasu 黑彝 |

ca. 9% |

ca. 59% |

|

Tusu 白彝 |

ca. 90% |

ca. 10% |

|

Lagea 红彝 |

ca. 0% |

ca. 5% |

|

Go 干彝 |

ca. 0% |

ca. 25% |

Table 1: Social Strata in Neasu und Nyisu (Guìzhōu)

|

Social Class |

Nuosu (Sìchuān) |

|---|---|

|

Nzymo 土司 |

ca. 1% |

|

Nuoho 黑彝 |

ca. 19% |

|

Quhuo 白彝 |

ca. 60% |

|

Gaxy |

ca. 20% |

|

|

|

Table 2: Social Strata in Nuosu (Sìchuān)

The interethnic relations of the Neasu and Ahmao were strained for a long time. The Yí landowners (and Hàn settlers) exploited the Ahmao people and treated them badly. Many episodes in Samuel Pollard’s diary and in his son’s accountWalter Pollard commented: “For years they had been in the grip of their overlords, whose policy was oppression; so harshly had they been burdened that despair had become a characteristic of the race, and they had come to accept poverty and sorrow, disease and death, as their inevitable heritage” (Pollard 1928: 152). See

Pollard, W., 1928, The life of Sam Pollard of China. London: Seeley. elaborate on the rude treatment of the Ahmao people by Yí and Hàn landlords. Excessive taxationWalter Pollard wrote: “At that time the Miao were a very downtrodden race. Chinese and Nosu overlords, who owned vast tracts of Miao territory, ruled over them with a cruel hand. From every measure of rice or bushel of corn produced by the Miao a large percentage had to be taken and delivered to the landlords as tax. (…) The Miao were groaning under the oppression heaped upon them. They were tired of being as a clod of earth, to be trampled on and passed by, and were yearning for the day when the race would grow like a spreading tree and be a power in the land” (Pollard 1928: 129-130). See

Pollard, W., 1928, The life of Sam Pollard of China. London: Seeley. was the means of interethnic suppression. In contrast to this gloomy scenario, it was the Ahmao who led the churches when both Ahmao and Neasu converted to the Christian faith and attended the same churches. The details of this reversal have been elucidated below.

(B) Customs: Like other Yí groups, the Neasu people are organized in clans and castes. The clans are of patrilineal lineage; membership to a Neasu clan is inherited from the father. Male membership is inalienable, while female membership changes when a woman marries a man from another clan.

White Neasu coupleNeasu clans tend to be exogamous but less than the Nuosu clans in Sìchuān. They favor marriage between cross-cousinsSee the Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles, Wēiníng Mínwěi (1997:63).

White Neasu coupleNeasu clans tend to be exogamous but less than the Nuosu clans in Sìchuān. They favor marriage between cross-cousinsSee the Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles, Wēiníng Mínwěi (1997:63).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社.. Marriage is preferably arranged between a man and his female cross-cousinThe female cross-cousin of a man is the daughter of his father’s sister or of his mother’s brother. From the woman’s perspective, he is the son of her mother’s brother or of her father’s sister.. The marriage of cross-cousins is always exogamous in case the marriage of their parents was exogamous. On the other hand, Neasu clans prohibit marriage between parallel cousinsA man should not marry the daughter of his father’s brother or of his mother’s sister. See the Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles, Wēiníng Mínwěi (1997:63).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社.. However, this arrangement cannot completely avoid endogamous marriage within a clan, despite impeding it. If a man marries the daughter of his mother’s sister, and his mother and aunt happen to have married men of the same clan, their marriage is deemed endogamous. Nevertheless, the Neasu strongly prefer marriage across clans and do so for the purpose of establishing kinship networks.

Furthermore, the three Neasu castes, Neasu landowners, Black Neasu, White Neasu, are strictly endogamous although there have been recent relaxations due to the social changes taking place during the 21st century. Samuel Pollard reports the storySee Pollard (1921: 137-138).

Pollard, S., 1921, In Unknown China. London: Seeley. of an Anzumo (landowner) who started a love affair with a slave girl. He implored Pollard to allow him to become Christian because he thought that his conversion would make him impervious to the attacks of his own relatives which he endured due to the union with the slave girl. Since the man insisted on continuing ancestor worship as well, Pollard turned down his request. When his relatives later found the slave girl, they beat her and put her in a pit where she eventually died an awful death. Therefore, a landowner (Tŭsī) traditionally marries a landowner, a Black Neasu marries a Black Neasu, and a White Neasu marries a White Neasu.

Neasu countrywomanUnlike the Nuosu in Sìchuān who cremate their dead, the Neasu practice inhumation. Before the Míng dynasty (1368-1644), the Neasu used to practice cremation as well but shifted to inhumationSee the Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles, Wēiníng Mínwěi (1997:67).

Neasu countrywomanUnlike the Nuosu in Sìchuān who cremate their dead, the Neasu practice inhumation. Before the Míng dynasty (1368-1644), the Neasu used to practice cremation as well but shifted to inhumationSee the Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles, Wēiníng Mínwěi (1997:67).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社. afterwards. Upon a person’s demise, a Shaman is called for reading ritual texts (指路经) in order to guide the soul of the dead person to the ancestor’s place in the afterworld.

The Neasu celebrate the Torch Festival (火把节) on the 24th of June every year like other Yí groups. The foundational myth behind this festival is similar to other Yí groups. For the Neasu in Wēiníng, the reason for lighting torches is to commemorate the daySee the Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles, Wēiníng Mínwěi (1997:73). By contrast, the Nuosu in Liángshān (Sìchuān) celebrate the Torch Festival to commemorate a legend, according to which the Yí ancestors fought pests sent by the god Entiguzi in order to destroy their crops. By holding up torches they defeated the pests as well as the god who sent them. when the ancestors overcame an invasion of locusts by burning them and thereby rescuing the harvest.

As evidenced in other Yí groups, the Neasu calendar incorporate element of the Chinese zodiac (shēngxiào 生肖) which has wide circulation in East Asia. In particular, it uses the twelve zodiac animals to divide days, months and years, although the order differs from the Hàn calendar. The Neasu month-cycle commences with the Neasu New Year in November, which is the month of the Rat. The calendar is the same as in the Nuosu language that is listed below for referenceSee Gerner (2013: 59).

Gerner, M., 2013, The Grammar of Nuosu. MGL 64. Berlin: Mouton..

|

|

Zodiac Term |

Neasu |

Nuosu |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(November) |

‘month / year of rat’ |

hxa |

hngup / kaol |

hxie |

hlep / kut |

ꉌꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(December) |

‘month / year of ox’ |

nyue |

hngup / kaol |

nyi |

hlep / kut |

ꑌꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(January) |

‘month / year of tiger’ |

nyeat |

hngup / kaol |

lat |

hlep / kut |

ꆿꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(February) |

‘month / year of rabbit’ |

tap hlup |

hngup / kaol |

tep hlep |

hlep / kut |

ꄯꆪꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(March) |

‘month / year of dragon’ |

lu |

hngup / kaol |

lu |

hlep / kut |

ꇐꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(April) |

‘month / year of snake’ |

shel |

hngup / kaol |

shy |

hlep / kut |

ꏂꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(May) |

‘month / year of horse’ |

mu |

hngup / kaol |

mu |

hlep / kut |

ꃅꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(June) |

‘month / year of sheep’ |

hxaop |

hngup / kaol |

yo |

hlep / kut |

ꑿꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(July) |

‘month / year of monkey’ |

nvaol |

hngup / kaol |

nyut |

hlep / kut |

ꑙꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(August) |

‘month / year of rooster’ |

wa |

hngup / kaol |

va |

hlep / kut |

ꃬꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(September) |

‘month / year of dog’ |

qii |

hngup / kaol |

ke |

hlep / kut |

ꈌꆪ / ꈎ |

|

(October) |

‘month / year of pig’ |

val |

hngup / kaol |

vot |

hlep / kut |

ꃮꆪ / ꈎ |

Table 3: Neasu and Nuosu Calendar

Religion

Neasu Bumo(A) Traditional Religion: The foundation of the Neasu religion is similar to that of the Nuosu religion and is laid down in the so-called ‘Yí Classics’. The religion is polytheistic and animist, non-dogmatic, and practical. The Neasu people use the term se21Compare with the cognate Nuosu term si33. to denote deities, mi33se21 to refer to heavenly gods (hidden gods in heaven and weather phenomena), and mi13se21 for earthly gods (stones, rivers, trees). The Neasu people worship, placate, and offer sacrifices to these deities. In addition, they revere four types of totemsThe English term ‘totem’ was borrowed from Ojibwe, a native American language. A totem refers to a sacred object or an abstract symbol that serves as an emblem for a people or a clan. in a rather implicit manner: a bamboo totemOne myth explains the special connection of the Go or Dry Yí 干彝 with bamboo and why the Go manufacture bamboo products. Bamboo is viewed as a hero of the Go. (See Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles 1997: 121).

Neasu Bumo(A) Traditional Religion: The foundation of the Neasu religion is similar to that of the Nuosu religion and is laid down in the so-called ‘Yí Classics’. The religion is polytheistic and animist, non-dogmatic, and practical. The Neasu people use the term se21Compare with the cognate Nuosu term si33. to denote deities, mi33se21 to refer to heavenly gods (hidden gods in heaven and weather phenomena), and mi13se21 for earthly gods (stones, rivers, trees). The Neasu people worship, placate, and offer sacrifices to these deities. In addition, they revere four types of totemsThe English term ‘totem’ was borrowed from Ojibwe, a native American language. A totem refers to a sacred object or an abstract symbol that serves as an emblem for a people or a clan. in a rather implicit manner: a bamboo totemOne myth explains the special connection of the Go or Dry Yí 干彝 with bamboo and why the Go manufacture bamboo products. Bamboo is viewed as a hero of the Go. (See Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles 1997: 121).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社., a crane totemThe crane is viewed as the king of birds with the ability of guiding the spirit of the dead in the thereafter to new address. In practice, the Bumo (the Neasu priest) sacrifices a hen or rooster as substitute for the crane to provide guidance to the dead (see Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles 1997: 121).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社., a tiger totemIn the mountains of Western Guìzhōu, the tiger is feared as a natural enemy due to its ferocious attributes (see Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles 1997: 121).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社. and a dragon totemSimilar to other ethnic groups in China and around the world, the dragon is considered to be an inflated and empowered snake whose might is feared (see Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles 1997: 121).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社.. The origin of these totems is based on fuzzy myths with variable circulation. The Neasu also worship the spirits of the ancestors. Like the Nuosu, the Neasu believe that a person has three spirits who return to three different addresses upon their demise: the individual spirit, the family spirit, and the clan spirit. Ancestral spirits who do not find their address come back and harass the living people. The main function of the Neasu priest, who is known as bumoIn Sìchuān, the priest is called ‘bimo’ and in Yúnnán he is called ‘bemo’. The term is composed of the Proto-Loloish verb bi ‘read’ and the augmentative suffix mo (‘master’, ‘chief’, ‘mother’)., is to ensure that the three spirits find their addresses in the afterworld and do not return. He sacrifices a hen or rooster and chants ritual texts at funerals in order to monitor the journey of the spirits.

The Neasu folk religion recognize two offices, the offices of the bumo ‘priest’ and of the suni ‘shaman’. In the paradigm of communist historiography, both offices are leftoversSee Wēiníng Nationality Chronicles (1997: 124-125).

Wēiníng Mínwěi 威宁民委, 1997, Nationality chronicles of the Wēiníng Yí, Huí, Miáo, Autonomous County 《威宁彝族回族苗族自治县民族志》. Guìyáng 贵阳: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社. of the primitive stage which is then subdivided into a matrilineal and patrilineal phase. The suni represents the early matrilineal stage, the bumo the latter patrilineal stage. A suni is often a woman and sometimes a man, whereas the office of a bumo must be represented by a man. The suni possesses magical powers put at the disposal of the person who requests services. The suni manipulates spirits in order to rescue a bad situation or to inflict harm. As is the case with the Nuosu folk religion, there are no restrictions in terms of caste, clan, or gender for the office of suni. Everyone with an experience of interaction with spirits can assume the office of suni. By contrast, a bumo is male, is often a White Neasu, and is educated in the traditional script (generally by his father who already is a bumo). The bumo performs rituals and interacts with spirits only by chanting existing ritual texts previously learnt by him.

(B) Christianity: Today, a wide network of Neasu and Nyisu churches spans over Western Guìzhōu which can be traced back to the endeavors of the China Inland Mission 内地会 (CIM), the Methodist Bible Christian MissionThe Bible Christian Church was founded by William O’Bryan (1778-1868) in Cornwall, England, in 1815. (See Tiedemann 2009: 129-130.) The Bible Christian Church split away from the Wesleyan Methodists before reuniting with the Methodist New Connexion and the United Methodist Free Church in 1907 in order to form the United Methodist Church. The first foreign mission of the Bible Christian Church was established in Canada in 1845. A mission station was opened in Yúnnán province with three centers: in Kūnmíng, in Dōngchuān, and in Zhāotōng. After Samuel Pollard joined the mission, a fourth center was established in Shíménkǎn, Guìzhōu province, in 1904, which proved to be one of the most successful ministries in Southwest China.

Tiedemann, R. G., 2009, Reference guide to missionary societies in China: From the 16th to the 20th centuries. London: Routledge. 循道会 (BCM) and the Friedenshort Deaconess Mission 女执事会 (FDC) in the early 20th century. In 1888, the CIM missionary James Adams 党居仁 established a station in Ānshùn 安顺 and commenced missionary workSee Enwall (1994: 93) and Wàng (1985: 10). See

Enwall, J., 1994, A myth become reality. History and development of the Miao written language. Vol. 1 & 2. University of Stockholm.

Wàng Míngdào 王明道, 1985, “History of the Gébù Church before liberation” “解放前葛布教会史”, Historical materials on religion in Guìzhōu 《贵州宗教史料》, pp. 10-21. among the Miáo 苗 in the neighboring villages. In 1903, a group of roaming Ahmao natives from Wēiníng county arrived in Ānshùn and were subsequently evangelized by Adams (Ahmao is the selfname of the Miáo in Wēiníng county and of those in Ānshùn prefecture although they speak different dialects). They responded to his respectful treatment and began propagating the Christian faith among their fellows back in Wēiníng. After his assistants visited Wēiníng, Adams made plans for building a church in Gébù 葛布Gébù 葛布 is a village in Fǔchùxiāng township 辅处乡 in Hèzhāng 赫章 county at the border to Wēiníng 威宁 county. Gébù and Ānshùn are at a distance of at least 230km. village in 1904, but hesitated due to the long distance from Ānshùn. He introduced some of the Ahmao believers to the BCM missionary Samuel Pollard who was stationed in Zhāotōng city, Yúnnán province, close to Wēiníng. However, Adams decided to proceed with his plan of building a church in Gébù and commissioned two Ahmao, Yáng Qìngān 杨庆安 and Chén Zǐmíng 陈子明, with the construction of the building that was eventually completed in 1905. Those Ahmao believers whom Adams referred to Samuel Pollard 柏格理 in Zhāotōng city found him there in July 1904. Once the contact was established, a constant stream of Ahmao people reached the mission station, eager to be instructed in the new faith. In 1905, Pollard purchased ten acres of land from a Neasu landowner in Shíménkǎn 石门坎Shíménkǎn 石门坎 belongs to Wēiníng county in Guìzhōu and is at a short distance from Zhāotōng in Yúnnán. and opened a new mission station there. He then instructed the Ahmao believers, planted churches, learnt the Ahmao language, created a phonemic script (the “Pollard Script”), and completed the New Testament in 1915, weeks before he died from typhoid fever.

Wàng Míngdào 王明道See Wàng (1985:14). Wàng Míngdào 王明道, the leader of the Gébù church, happens to bear the same name as Wàng Míngdào 王明道, the pastor of the Christian Tabernacle church in Běijīng 北京, one of the most influential Chinese Christian personalities of the 20th century (see Harvey, 2002). However, both personalities are unrelated. Wàng, the pastor of the Gébù church, reports events that he personally witnessed during the first three decades of the 20th century. His church history was published in 1985 as an article following his death. See

Harvey, T. A., 2002, Acquainted with Grief: Wang Mingdao's Stand for the Persecuted Church of China. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Brazos Press.

Wàng Míngdào 王明道, 1985, “History of the Gébù Church before liberation” “解放前葛布教会史”, Historical materials on religion in Guìzhōu 《贵州宗教史料》, pp. 10-21. reports that Samuel Pollard and James Adams agreed on dividing Western Guìzhōu into two spheres of influence, the western part being served by Pollard’s Bible Christian Mission, and the eastern part by Adam’s China Inland Mission. The Gébù church at the border of Wēiníng and Hèzhāng counties was supervised by the CIM but was relatively independent because of the long distance to Ānshùn. The members were active in planting churches all over Western Guìzhōu. Between 1905 and 1919, the majority of these converts were Ahmao people. After 1919, it was the Neasu people who became Christians in great numbers.

The Gébù church was at the center of a remarkable development. Since the beginning in 1905, regular baptisms were held after assuring that the neophytes were ready to renounce to previous practices such as ancestor worship. After overcoming the initial opposition of a Yí landlord, an elementary school was opened in 1906, with one Hàn teacher instructing more than 20 Miáo and Yí pupils. In 1909, four new churches grew out of the Gébù church, in Xīnglóngchǎng 兴隆厂 township (Wēiníng), Dàsōngshù 大松树 township (Wēiníng), Qiūwān 鳅湾 township (Wēiníng), and Lúfáng 炉房 township (Hèzhāng). A year later in 1910, the village and the church in Gébù were destroyed by fire. The church was rebuilt - this time not with wooden material but with stone bricks – under the auspices of James Adams and using funds of the China Inland Mission. The church regained strength by 1912 and evangelized the ethnic groups of neighboring counties: Hèzhāng 赫章, Nàyōng 纳雍, Bìjié 毕节, Dàfāng 大方 and Shuǐchéng 水城. Initially, the response of the Neasu (and Nyisu) was limited, but altogether ten new churches were planted and the number of believers surpassed 1,000. In 1914, complaints about Chén Zǐmíng 陈子明, the principal elder of the Gébù church since its inception, were voiced with regard to his inappropriate leadership style. James Adams therefore appointed Zhāng Bǎoluó 张保罗, a native Ahmao from Gébù, as the responsible elder, but Zhāng died just after one year in service. In the same year of 1915, James Adams was struck by lightning and died. After a difficult transition, the CIM missionary Issac Page 裴忠谦 shifted to Gébù in 1916 as the responsible missionary of the church.

The Gébù church was at the center of a remarkable development. Since the beginning in 1905, regular baptisms were held after assuring that the neophytes were ready to renounce to previous practices such as ancestor worship. After overcoming the initial opposition of a Yí landlord, an elementary school was opened in 1906, with one Hàn teacher instructing more than 20 Miáo and Yí pupils. In 1909, four new churches grew out of the Gébù church, in Xīnglóngchǎng 兴隆厂 township (Wēiníng), Dàsōngshù 大松树 township (Wēiníng), Qiūwān 鳅湾 township (Wēiníng), and Lúfáng 炉房 township (Hèzhāng). A year later in 1910, the village and the church in Gébù were destroyed by fire. The church was rebuilt - this time not with wooden material but with stone bricks – under the auspices of James Adams and using funds of the China Inland Mission. The church regained strength by 1912 and evangelized the ethnic groups of neighboring counties: Hèzhāng 赫章, Nàyōng 纳雍, Bìjié 毕节, Dàfāng 大方 and Shuǐchéng 水城. Initially, the response of the Neasu (and Nyisu) was limited, but altogether ten new churches were planted and the number of believers surpassed 1,000. In 1914, complaints about Chén Zǐmíng 陈子明, the principal elder of the Gébù church since its inception, were voiced with regard to his inappropriate leadership style. James Adams therefore appointed Zhāng Bǎoluó 张保罗, a native Ahmao from Gébù, as the responsible elder, but Zhāng died just after one year in service. In the same year of 1915, James Adams was struck by lightning and died. After a difficult transition, the CIM missionary Issac Page 裴忠谦 shifted to Gébù in 1916 as the responsible missionary of the church.

PentecostApse of Chapel Miniscalchi in Saint Anastasia's church in Verona, Italy, designed by Angelo di Giovanni in 1506 with main scene of the Pentecost.In 1918, Page coordinated a campaign of evangelization among the Neasu in Hèzhāng which proved to be more successful than the previous campaign of 1912. In the Republican period (1911-1949), the feudal system broke up, leading to a sense of insecurity among the ethnic societies. This climate contributed to the successful evangelization among the Neasu. Several Neasu churches were established in different districts of Hèzhāng. In 1919, Isaac Page left for retirement in England and was succeeded by the English CIM missionary John Yorkston 岳克敦. After settling down in Hèzhāng and in order to better attend the needs of the Ahmao and Neasu believersAccording to a report of the Jiégòu Church Editorial Group (1985:22), 40 percent, 50 percent, and 10 percent of the Gébù Church comprised of Ahmao, Neasu, and Hàn people, respectively. See

PentecostApse of Chapel Miniscalchi in Saint Anastasia's church in Verona, Italy, designed by Angelo di Giovanni in 1506 with main scene of the Pentecost.In 1918, Page coordinated a campaign of evangelization among the Neasu in Hèzhāng which proved to be more successful than the previous campaign of 1912. In the Republican period (1911-1949), the feudal system broke up, leading to a sense of insecurity among the ethnic societies. This climate contributed to the successful evangelization among the Neasu. Several Neasu churches were established in different districts of Hèzhāng. In 1919, Isaac Page left for retirement in England and was succeeded by the English CIM missionary John Yorkston 岳克敦. After settling down in Hèzhāng and in order to better attend the needs of the Ahmao and Neasu believersAccording to a report of the Jiégòu Church Editorial Group (1985:22), 40 percent, 50 percent, and 10 percent of the Gébù Church comprised of Ahmao, Neasu, and Hàn people, respectively. See

Jiégòu Church Editorial Group 结构教会志编写组, 1985, Concise History of the Jiégòu Church 结构教会简史, in Historical materials on religion in Guìzhōu 《贵州宗教史料》, pp. 22-23., Yorkston and his associates separated the Neasu believers and formed a new church in 1920, known as the Jiégòu 结构 churchJiégòu 结构 is a township in Hèzhāng county.. A new building for the Jiégòu church was erected in 1921. This church emerged as the center of outreach to the Neasu people in the region. Starting from 1923, the China Inland Mission encouraged the churches of Western Guìzhōu to become financially and spiritually independentThis idea became later enshrined in Máo Zédōng’s religious policy evidenced by the concept of the Three-Self Church: ‘self-preaching’, ‘self-governance’, and ‘self-financing’. from European support. As the political situation in Southwest China became unstable, many foreign missionaries (including John Yorkston in Gébù) left their mission station by 1927. During the same year, the CIM held a provincial conference where Wàng Míngdào 王明道Wàng Míngdào 王明道 is the author of the church history on which part of this section is based (Wàng 1985). See

Wàng Míngdào王明道, 1985, “History of the Gébù Church before liberation” “解放前葛布教会史”, Historical materials on religion in Guìzhōu 《贵州宗教史料》, pp. 10-21. was instituted as the responsible elder of the Gébù church, and Ān Wénliáng 安文良 as the elder in charge of the Jiégòu church. In 1930, the Gébù and Jiégòu churches combined forces before planting three new Ahmao and Neasu churches in Wēiníng, one Neasu church in Hèzhāng, and one Neasu church in Yíliáng 彝良 county (Yúnnán).

Within a span of few years, the churches in Western Guìzhōu became mature, self-supporting, and self-multiplying. The network of churches planted over forty years is summarized in the following tableSee Wàng (1985: 20-21).

Wàng Míngdào 王明道, 1985, “History of the Gébù Church before liberation” “解放前葛布教会史”, Historical materials on religion in Guìzhōu 《贵州宗教史料》, pp. 10-21..

|

Year |

Church |

Responsible Elder |

|---|---|---|

|

1905 |

Hèzhāng Gébù 赫章葛布 |

Chén Zǐmíng 陈子明 |

|

1909 |

Wēiníng Xīnglóngchǎng 威宁兴隆厂 |

Zhāng Mǎkě 张马可 |

|

|

Wēiníng Dàsōngshù 威宁大松树 |

Lǐ Yàsā 李亚撒 |

|

|

Wēiníng Yúqiūwān 威宁鱼鳅湾 |

Wáng Yǐxījié 王以西结 |

|

|

Hèzhāng 5thDistrict, Xīnlúfáng 赫章五区新炉房 |

Luó Dànyǐlǐ罗但以理 |

|

1912 |

Hèzhāng 4thDistrict, Héshān Village 赫章四区合山寨 |

Mǎ Yàshè 马亚设 |

|

1913 |

Hèzhāng 2ndDistrict, Bāobāo Village 赫章二区包包寨 |

|

|

|

Hèzhāng 2ndDistrict, Yějī Village 赫章二区野鸡寨 |

|

|

|

Shuǐchéng Yántóushàng Village 水城岩头上寨 |

|

|

|

Shuǐchéng Càigāndān Village 水城菜甘丹寨 |

|

|

|

Shuǐchéng YějīVillage 水城野鸡寨 |

|

|

|

Nàyōng Gébù 纳雍葛布 |

|

|

1917 |

Hèzhāng 4thDistrict, Másāigōushuǐyíng 赫章四区麻腮沟水营 |

Luó Dànyǐlǐ罗但以理 |

|

1918 |

Wēiníng Jiàodǐngshān 威宁轿顶山 |

Zhāng Wénxī 张文熙 |

|

1920 |

Hèzhāng Jiégòu 赫章结构The Jiégòu Church Editorial Group (1985:22) reports 1910 as the year the Jiégòu church was established, but then corrects the date to 1920 on the same page. |

|

|

|

Hèzhāng Démùpíng 赫章德慕坪 |

Zhū Yìchéng 朱义成 |

|

|

Hèzhāng Gōngjī Village 赫章公鸡寨 |

Luó Suǒluóbābó 罗所罗巴伯 |

|

|

Wēiníng 10thDistrict, Yǐdú 威宁十区以独 |

|

|

|

Wēiníng 11thDistrict, Mǎlāchòng 威宁十一区马拉冲 |

|

|

1922 |

Hèzhāng 4thDistrict, Yánzú Village 赫章四区岩足寨 |

Wáng Guóchén 王国臣 |

|

|

Hèzhāng 5thDistrict, Ǎizipō 赫章五区矮子坡 |

Zhāng Xīmén 张西门 |

|

|

Hèzhāng 6thDistrict, Huáshíbǎn 赫章六区滑石板 |

Yáng Mǎkě 杨马可 |

|

1923 |

Hèzhāng 4thDistrict, Yántóushàng 赫章四区岩头上 |

Wáng Yuēhàn 王约翰 |

|

|

Yíliáng Máopō 彝良茅坡 |

MǎYuēshūyà 马约书亚 |

|

1927 |

Hèzhāng 4thDistrict, Liújiāwūjī 赫章四区刘家屋基 |

Wáng Shízhòng 王时中 |

|

1930 |

Wēiníng 3rdDistrict, Guāngmíngshān 威宁三区光明山 |

|

|

|

Wēiníng 3rdDistrict, Bùzǐshān 威宁三区不子山 |

|

|

|

Wēiníng 3rdDistrict, Bàodōu 威宁三区抱都 |

|

|

|

Hèzhāng 4thDistrict, Wāduōgōu 赫章四区洼多沟 |

|

|

|

Yíliáng Qūlǎoyīngshān 彝良屈老鹰山 |

|

|

1946 |

Hèzhāng 5thDistrict, Shuǐtángzǐ 赫章五区水塘子 |

Zhū Míngxīn 朱明新 |

Table 4: Churches in Western Guìzhōu (1905-1946)

After 1949, most churches were integrated into the network of Three-Self Churches, many of which continue to exist even to this day. In numerous villages, believers also attend informal gatherings in private homes.

About 90 kilometers further east, the German Friedenshort Deaconess MissionThe German name of the mission is ‘Friedenshort Diakonissenmission’. In 1900, Eva von Tiele Winckler founder of the Deaconess Motherhouse Friendenhort at Miechowitz, Upper Silesia, Germany (now Miechowice, Poland) got to know Hudson Taylor in Switzerland. Convinced about the urgency of the Great Commission, she decided to send missionaries to China in association with the China Inland Mission. The approach of this mission was to combine evangelization with charity services such as orphanages and hospitals. The Mission established fields in Hong Kong, Bìjié 毕节, Dàfāng 大方 (Guìzhōu), and Zhènxióng 镇雄 (Yúnnán). See Tiedemann (2009:164).

Tiedemann, R. G., 2009, Reference guide to missionary societies in China: From the 16th to the 20th centuries. London: Routledge. 女执事会 opened mission stations in the cities of Dàfāng大方 and Bìjié 毕节. During the 36 years of their ministry (1915-1951), 19 deaconesses from Germany and Switzerland participated in the ministry. Among them were Margarete Welzel 苏宽仁, Wanda Jener 晏玉英 and Dora Heierli 海贞利. After four deaconesses arrived in the city of Dàfāng in 1915, they purchased land, built a chapel, and opened other facilities such as an orphanage, an elementary school, and a hospital. Soon afterwards they were invited to the local prisonSee Welzel (1959: 43-45).

Welzel, M., 1959, Boten des himmlischen Königs, 40 Jahre Missionsarbeit in den Bergen Chinas. Freudenberg: Friedenshort Mission., dispensed medicine, and preached the Gospel to the prison population. These services helped overcome the initial distrust in the populationAccording to Welzel (1959:16) and Zhāng Chéngyáo (1985:28), rumors were spread among the ordinary people. One rumor focused on their green eyes with magic forces that would help them see treasures in the ground and steal them away (“洋婆子绿眼睛,透视地下三尺深,是来我国取宝的”). See

Welzel, M., 1959, Boten des himmlischen Königs, 40 Jahre Missionsarbeit in den Bergen Chinas. Freudenberg: Friedenshort Mission.

Zhāng Chéngyáo 张承尧, 1985, “The China Inland Mission’s Christian foundation work in Bìjié county” “毕节县基督教内地会创建经过”, Historical materials on religion in Guìzhōu 《贵州宗教史料》, pp. 28-31.. From the very beginning, the deaconesses organized Bible classes and evangelized the Ahmao, the Nyisu (whom they called Yíjiā 彝家) and the Hàn. They started to baptizeA missionary from the nearby China Inland Mission station in Qiánxī 黔西 conducted the baptism (Welzel 1959:22).

Welzel, M., 1959, Boten des himmlischen Königs, 40 Jahre Missionsarbeit in den Bergen Chinas. Freudenberg: Friedenshort Mission. converts in 1916, although spiritual progress was slow at the initial stages. Two deaconesses, Maria Vorkörper and Luise Täuber, died of disease in Dàfāng in 1928-1929See Welzel (1959:33-37).

Welzel, M., 1959, Boten des himmlischen Königs, 40 Jahre Missionsarbeit in den Bergen Chinas. Freudenberg: Friedenshort Mission.. In 1925, a small group of deaconesses moved from Dàfāng to the greater city of Bìjié in order to begin a second ministry there. They established a chapel around 1926.

The general situation turned unstable in the late 1920s when rival fractions of the nationalist army and robber armies fought for supremacy. When the China Inland Mission urged (British) missionaries in 1927 to withdraw from their mission stations, the deaconesses decided to stay back, but had to go through trials of war. Heavy shooting erupted in Bìjié after the city official evacuated his residence and a robber army filled the vacuum. Scores of soldiers, robbers, and local residents died in these shootings, while the deaconesses set up a military hospital to take care of the wounded See Welzel (1959:66).

Welzel, M., 1959, Boten des himmlischen Königs, 40 Jahre Missionsarbeit in den Bergen Chinas. Freudenberg: Friedenshort Mission.. Many locals sought refuge in the cellar of the chapel. Dramatic scenes unfolded in the hospital when a chief robber and a military officer both lied close to one another. The deaconesses negotiated a ceasefire that rescued the mission station from massacre. The situation was normalized when the robbers withdrew. Shortly thereafter, the deaconesses organized successful campaigns of evangelization among the Nyisu and Ahmao populations. After 1928, they founded five churches with more than 800 convertsSee Zhāng (1985: 31).

Zhāng Chéngyáo 张承尧, 1985, “The China Inland Mission’s Christian foundation work in Bìjié county” “毕节县基督教内地会创建经过”, Historical materials on religion in Guìzhōu 《贵州宗教史料》, pp. 28-31。. In 1936, the deaconesses were impelled to escape the advancing communist troops who looted the mission station. The local Christians fled to caves in the mountains from where they watched the devastation of the facilities. The deaconesses escaped via Kūnmíng 昆明 into Hong Kong. Since the communist army pushed westwards, they soon left Western Guìzhōu, which allowed the deaconesses to return to their mission stations in 1937. They brought along a tent for 150 peopleSee Welzel (1959:94).

Welzel, M., 1959, Boten des himmlischen Königs, 40 Jahre Missionsarbeit in den Bergen Chinas. Freudenberg: Friedenshort Mission. which they had acquired in Hong Kong.

Tent of EvangelizationAfter training a team of local evangelists, the preachers toured the surrounding areas with the tent and spread the gospel to thousands of peopleSee Welzel (1959: 96).

Tent of EvangelizationAfter training a team of local evangelists, the preachers toured the surrounding areas with the tent and spread the gospel to thousands of peopleSee Welzel (1959: 96).

Welzel, M., 1959, Boten des himmlischen Königs, 40 Jahre Missionsarbeit in den Bergen Chinas. Freudenberg: Friedenshort Mission.. Missionary work continued throughout the 1940s until 1951 when they had to leave China after the Communists took control of the country. The deaconesses did not keep systematic record of all the neophytes and baptisms. It is estimated that there were a minimum of 2,000 people who were converted during the 36 years of ministryMargarete Welzel mentions 131 baptisms before 1925 (1959: 24); 282 men and women were baptized in 1935 alone. According to Chinese sources, 800 people converted to the Christian faith shortly after 1928 (Zhāng Chéngyáo 1985:28). Welzel reports that thousands of people heard the Gospel during one of the evangelization campaigns that were held in the tent after 1937 (1959:96). See

Welzel, M., 1959, Boten des himmlischen Königs, 40 Jahre Missionsarbeit in den Bergen Chinas. Freudenberg: Friedenshort Mission.

Zhāng Chéngyáo 张承尧, 1985, “The China Inland Mission’s Christian foundation work in Bìjié county” “毕节县基督教内地会创建经过”, Historical materials on religion in Guìzhōu 《贵州宗教史料》, pp. 28-31.. The churches they left were transformed into Three-Self-Churches.

Samuel Pollard translated the New Testament in Ahmao before 1917, but a translation of the scriptures in Neasu (or Nyisu) was not undertaken until recently. Members of RFLRSee Research Foundation Language and Religion. translated the New Testament into Neasu between 1997 and 2017. The first edition was published in 2018, one hundred years after the publication of the Ahmao New Testament. A short sketch of the translation process is presented on this webpage.

Language

The Neasu language belongs to the Burmese-Lolo group within the Tibeto-Burman language family, as shown on the map of Burmese-Lolo languages.

(A) Rare properties: Neasu exhibits several rare features in the sound system, morphology, and syntax which we describe in this section. We present the language data in the script used for the New Testament, which is introduced in the below section.

1. Phonology. Neasu uses retroflex consonants for eleven modes of articulation. These consonants contrast with alveolar consonants for each of these modes.

|

Mode of Articulation |

Retroflex |

Examples |

Alveolar |

Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Prenasalized voiced |

ndv [ɳɖ] |

ndval ‘drop’ |

nd [nd] |

ndup ‘beat’ |

|

Voiced |

ddv [ɖ] |

ddva ‘destroy’ |

dd [d] |

dda ‘rise’ |

|

Voiceless |

dv [ʈ] |

dvut ‘tell’ |

d [t] |

dul ‘incite’ |

|

Aspirated voiceless |

tv [ʈʰ] |

tvul ‘white’ |

t [tʰ] |

tut ‘arrange’ |

|

Prenasalised affricate |

nr [ɳɖɀ] |

nra ‘measure’ |

nz [ndz] |

nza ‘a drop’ |

|

Voiced affricate |

rr [ɖɀ] |

rrut ‘be willing’ |

zz [dz] |

zzup ‘grain’ |

|

Voiceless affricate |

zh [ʈȿ] |

zhu ‘feed’ |

z [ts] |

zut ‘good’ |

|

Aspirated voiceless affricate |

ch [ʈȿʰ] |

chul ‘sweet’ |

c [tsʰ] |

cu ‘salt’ |

|

Nasal |

nv [ɳ] |

nvut ‘affair’ |

n [n] |

nul ‘hear’ |

|

Voiced fricative |

r [ɀ] |

rat ‘forgive’ |

ss [z] |

ssal ‘go down’ |

|

Voiceless fricative |

sh [ȿ] |

sha ‘Hàn’ |

s [s] |

sal ‘air’ |

Table 5: Eleven retroflex versus alveolar consonants

2. Morphology. The Neasu determiner systemThe data presented here were published previously in Gerner (2003, 2012b).

Gerner, M., 2003, Demonstratives, articles and topic markers in the Yi group. Journal of Pragmatics 35(7), 947-998.

Gerner, M., 2012b, Historical change of word classes. Diachronica 29(2), 162-200.uses three demonstrative pronouns, two definite articles, and one topic marker.

|

Determiner |

Proximal |

Medial |

Distal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Demonstratives |

tat |

nat |

ggat |

|

Definite articles |

tao |

|

ggaot |

|

Topic marker |

|

nao |

|

Table 6: Determiners in Neasu

The topic marker and the definite articles developed from the demonstrative pronouns in an ancestor language of Neasu. These three demonstratives merged with the old now obsolete classifier *mo to form definite articles. The initial consonant [m] of the classifier was lost in a sound change called aphaeresis. The merger was completed by the loss of the vowel in the demonstratives (called apocope) as well as by lowering the tone (lenition).

|

Demonstrative |

Classifier |

|

Aphaeresis |

|

Apocope and Tone Lenition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

tʰa55 |

mo33 |

|

tʰa55 + o33 |

|

tʰɔ33 |

|

na55 |

mo33 |

|

na55 + o33 |

|

nɔ33 |

|

ga55 |

mo33 |

|

ga55 + o33 |

|

gɔ55 |

Table 7: Phonological changes

The merged demonstratives were reanalyzed as definite articles, but preserved the deictic meaning of distance (proximal, medial and distal). They occur in noun phrases mentioned in discourse for the third time, while the unmerged demonstratives were used in noun phrases mentioned for the second time. The medial definite article was further reanalyzed as topic marker. An overview of the changes is presented below.

|

Modern Demonstratives |

Old Demonstratives |

Modern Definite Articles |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

replaced |

|

|

|

|

|

|

grammaticalized |

|

|

|

hnu cao |

tat |

yao |

|

*hnu cao |

tat |

mo |

|

|

|

|

hnu cao |

tao |

|

person |

DEM.PROX |

CL |

|

person |

DEM.PROX |

CL |

|

|

|

|

person |

ART.PROX |

|

‘this person’ |

|

‘this person’ |

|

‘the person here’ |

||||||||

|

hnu cao |

nat |

yao |

|

*hnu cao |

nat |

mo |

|

*hnu cao |

nao |

|

hnu cao |

nao |

|

person |

DEM.MED |

CL |

|

person |

DEM.MED |

CL |

|

person |

ART.MED |

|

person |

TOP |

|

‘that person there’ |

|

‘the person there’ |

|

‘the person there’ |

|

‘Person (Topic)’ |

||||||

|

hnu cao |

ggat |

yao |

|

*hnu cao |

ggat |

mo |

|

|

|

|

hnu cao |

ggaot |

|

person |

DEM.DIST |

CL |

|

person |

DEM.DIST |

CL |

|

|

|

|

person |

ART.DIST |

|

‘that person far away’ |

|

‘that person far away’ |

|

‘the person far away’ |

||||||||

Table 8: Grammaticalization of Neasu determiners

3. Syntax. Neasu uses a meta-sequential prefix (ao-)This peculiar prefix was first reported at a syntactic conference, see Gerner (2012a).

Gerner, M., 2012a, A meta-linguistic prefix in Neasu, paper presented at the Workshop on Complex Sentences, Embedding and Recursivity, held at the University of Konstanz (Germany), March 5-6, 2012. that can be attached to six adverbs and conjunctions to form new conjunctions. The prefixed conjunctions differ syntactically from the unprefixed conjunctions in the complexity of their binding domain. Notably, the binding domain (BD) of an adverb or conjunction refers to the number of clauses on which a coherent interpretationFor a definition of binding domain in Generative Grammar, see

Gerner, M., 2012a, A meta-linguistic prefix in Neasu, paper presented at the Workshop on Complex Sentences, Embedding and Recursivity, held at the University of Konstanz (Germany), March 5-6, 2012. depends. When the unprefixed forms have a mono-clausal binding domain, their prefixed counterparts have a bi-clausal binding domain. On the other hand, when the unprefixed conjunctions have a bi-clausal binding domain, the prefixed conjunctions depend on larger discourse portions, i.e. on binding domains which comprise of several clauses. The function of these prefixed conjunctions is to stratify the larger discourse.

|

Adverb |

Phrasal conjunction |

|

Clausal conjunction |

|

Discourse conjunction |

|

BD: one clause |

BD: one clause |

|

BD: two clauses |

|

BD: several clauses |

|

jiit ‘all’ |

|

|

ao jiit ‘moreover’ |

|

|

|

|

nu ‘or’ |

|

ao nu ‘or’ |

|

|

|

|

nyi ‘and’ |

|

ao nyi ‘and’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

set ‘unless’ |

|

ao set ‘therefore’ |

|

|

|

|

ze ‘then’ |

|

ao ze ‘finally’ |

|

|

|

|

ddet ‘but’ |

|

ao ddet ‘however’ |

Table 9: Prefix class of ao- in Neasu

Peter GrundySee Peter Grundy (2000: 206). See

Grundy, P., 2000, Doing Pragmatics. New York: Arnold. calls the function of a form ‘meta-sequential’ if it indicates the place of the utterance in the wider discourse. In now, I have done it, the form now marks a new topic within a wider discourse and is a meta-sequential marker. Since prefixation of the Neasu morpheme ao- exacerbates the complexity of the binding domain, we call it a meta-sequential prefix. Several illustrations are mentioned below.

|

(1) |

a. |

jiit ‘all’: |

Xip heat |

jiit |

ddeat ddao |

nap |

leat. |

|

|

|

|

|

BD: one clause |

3.PL |

all |

exit |

2.SG |

go |

|

|

|

‘They all went out towards you.’ |

|||||||||

|

|

b. |

ao jiit ‘moreover’: |

Ngop heat |

jiit |

zzu, |

ao jiit |

nryp |

ndaop |

ggol. |

|

|

|

|

BD: two clauses |

1.PL |

all |

eat |

moreover |

wine |

drink |

DP |

|

|

‘We all had a meal; moreover drank wine.’ |

||||||||||

|

(2) |

a. |

nu ‘or’: |

Xip heat |

ggat |

yi |

nu |

lup |

lea |

rrao |

ddeat ddao. |

|

|

|

|

BD: one clause |

3.PL |

DEM.DIST |

home |

or |

city |

CL |

COV.be at |

exit |

|

|

‘They left that house or that city.’ |

|||||||||||

|

|

b. |

ao nu ‘or’: |

xip |

keap seat |

ddut |

hxit, |

ao nu |

eap zheat |

ddut |

hxit, |

xip |

wo |

mat |

se. |

|

|

|

|

BD: two clauses |

3.SG |

how |

word |

say |

or |

what |

word |

say |

3.SG |

GET |

NEG |

know |

|

|

‘He does not know how to put it or what to say.’ |

|||||||||||||||

|

(3) |

a. |

set ‘unless’: |

Nap |

geat |

heap caop |

tap |

zzea |

ngu |

lyip |

si |

tveat |

bao, |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

BD: two clauses |

2.SG |

going to |

ax |

NUM.1 |

CL |

borrow |

come |

tree |

put |

down |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

set |

ngop |

mot |

nap |

wo |

zzu |

ddop |

ye. |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

unless |

1SG |

toward |

2.SG |

GET |

eat |

can |

EXCL |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

‘Go, take an ax and unless you fell the tree, you cannot eat me.’ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

b. |

ao set ‘therefore’: |

Xip |

gie |

mup |

xiil |

hop |

nduet. |

Ao set |

gie |

xip |

map |

bbiit |

ddeat |

map |

hxit. |

|

|

|

BD: several clauses |

3.SG |

OBJ |

make |

die |

SEND |

think |

therefore |

OBJ |

3.SG |

NEG |

give |

say |

NEG |

can |

|

‘He wanted to kill the frog. Therefore, he could not say anything about (his intention of) giving her (to the frog).’ |

||||||||||||||||

|

(4) |

a. |

ze ‘then’: |

na liit |

gao |

wop |

keap |

ze |

lal |

chyp |

rrea |

kiet |

gat |

sy. |

|

|

|

BD: two clauses |

name |

LOC |

GET |

arrive |

then |

hand |

stretch |

livestock |

on |

put |

touch |

|

‘Nali arrived and inspected then the livestock.’ |

|||||||||||||

|

|

b. |

ao ze ‘finally’: |

(last sentence in story) |

Ao ze |

qil bbu |

ssil ggao |

kaop ngea |

wu dvut |

hxil, |

si |

bao |

||||||||

|

|

|

BD: several clauses |

|

finally |

tiger |

leopard |

all |

under |

stand |

tree |

collapse |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

ssal |

lyip |

ze |

yiip bel |

diil |

xiil |

hol. |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

descend |

come |

then |

whole, all |

smash |

die |

SEND |

||||||||||

|

‘In the end, all the tigers and leopards stood under the tree which collapsed and smashed them.’ |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

(5) |

a. |

ddet ‘but’: |

Xip |

neat sul |

ngea, |

ddet |

xip |

sha |

mba |

hxit. |

|

|

|

BD: two clauses |

3.SG |

Neasu |

COP |

but |

3.SG |

Chinese |

language |

speak |

|

‘He is Neasu, but he can speak Chinese.’ |

||||||||||

|

|

b. |

ao ddet ‘however’: |

Xip heat |

geat |

leat |

mep met |

yaop |

hxaop |

gie |

fu |

hop. |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

BD: several clauses |

3.PL |

going to |

go |

each |

REFL |

sheep |

OBJ |

kill |

SEND |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

Ao ddet |

sset mu lep shel |

gao |

mat |

njop. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

however |

camel |

LOC |

NEG |

pass |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

‘They went and killed their own sheep (thinking that camels would pass by). However, no camel passed by.’ |

||||||||||||||||||||

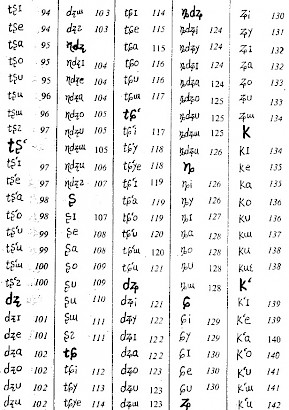

(B) Writing system: Many Chinese minority languages have Romanized writing systems that were commissioned by the Chinese government in the 1950s. However, the Neasu language was excluded from this program, because the more prestigious Nuosu language in Sìchuān was the beneficiary instead. Members of RFLRSee Research Foundation Language and Religion. created a Romanized script for the Neasu language between 1997 and 2006, which was used to translate the New Testament. We present a sketch below.

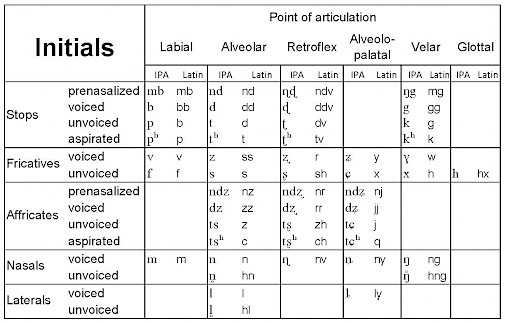

Neasu exhibits 49 consonant phonemes that are presented below in the Romanized script and in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Remarkable features of the consonant system are the four fully contrastive phonation types, prenasalized, voiced, unvoiced, aspirated, and the set of eleven retroflex consonants (pointed out above). Contrastive sets of words are presented below for each phonation type and point of articulation.

|

mb |

bb |

b |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

bbep ‘fall’ |

bet ‘hide’ |

pet ‘rotten’ |

|

mba ‘word’ |

bbat ‘small’ ‘’ |

ba ba ‘bread’ |

pap ‘side’ |

|

mbu ‘clothes’ |

bbu ‘toward’ |

bu ‘struggle’ |

put ‘people’ |

|

nd |

dd |

d |

t |

|---|---|---|---|

|

nde ‘upside’ |

dde ‘knock’ |

del ‘fog’ |

tep ‘run’ |

|

|

dda ‘up’ |

da ‘chest’ |

tap ‘one’ |

|

ndup ‘hit’ |

ddu ‘hole’ |

dul ‘incite’ |

tut ‘design’ |

|

ndv |

ddv |

dv |

tv |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ndvi hlaot ‘win’ |

ddvi ‘tasteless’ |

gu dvi ‘punish’ |

tvil ‘change’ |

|

ndval ‘tumble’ |

ddva ‘destroy’ |

dva ‘strike’ |

tvut ‘tell’ |

|

|

ddvu yii ‘honey’ |

dvut ‘say’ |

tvul ‘white’ |

|

mg |

gg |

g |

k |

|---|---|---|---|

|

mgii ‘fake’ |

ggiil ‘rebellious’ |

|

mii kiil ‘night’ |

|

mgal ‘call’ |

ggat ‘let’ |

gal ‘twig, branch’ |

ka ‘basket’ |

|

mgup ‘heal’ |

ggup ‘sing’ |

gup ‘persecute’ |

kul ‘shout’ |

|

f |

v |

|---|---|

|

fep ‘dry’ |

vep ‘buy’ |

|

fal ‘rock’ |

va ‘pig’ |

|

fu ‘kil’ |

vut ‘sell’ |

|

ss |

s |

r |

sh |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

shi ‘attach’ |

|

ssep ‘pillar’ |

set ‘know’ |

|

|

|

ssal ‘descend’ |

sal ‘air’ |

rat ‘forgive’ |

sha ‘Han’ |

|

ssu ‘son’ |

su ‘book’ |

|

shu ‘bitter’ |

|

y |

x |

w |

h |

hx |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

yi ‘also’ |

xip ‘he’ |

|

|

hxit ‘say’ |

|

yiip ‘water’ |

xiil ‘die’ |

|

hiil ‘new’ |

|

|

yal ‘crime’ |

|

wa ‘hen’ |

shut hal ‘decorate’ |

|

|

yo ‘itchy’ |

|

wop ‘get’ |

hop ‘bring’ |

|

|

yaop ‘oneself’ |

|

waol bu ‘belly’ |

|

hxaop ‘see’ |

|

nz |

zz |

z |

c |

|---|---|---|---|

|

nzel ‘worthy’ |

zzep ‘root’ |

ze ‘then’ |

cel ‘oil’ |

|

xue nza ‘drop of blood’ |

nya zza ‘trample’ |

zap ‘move’ |

ca ‘finish’ |

|

ap nzup ‘governor’ |

zzup ‘crops’ |

zut ‘good’ |

cu ‘salt’ |

|

nr |

rr |

zh |

ch |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ddvep nri ‘rich’ |

rril ‘broken’ |

zhi ‘pull out’ |

chil ‘cool’ |

|

nra ‘weigh’ |

seat rra ‘resemble’ |

zha ‘calculate’ |

cha zzu ‘should’ |

|

nrup mop ‘pearl’ |

rrut ‘be willing’ |

zhu ‘feed’ |

chul ‘sweet’ |

|

nj |

jj |

j |

q |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

ni jji ‘law’ |

ji ‘form’ |

qil ‘hand over’ |

|

njiip ‘skin’ |

jjiip ‘melt’ |

jiit ‘all’ |

qiil ‘foot’ |

|

|

ao jjal ‘clean’ |

|