Summary

This article was originally published by the Journal of Religious History, issue 42(2), pp. 145-180, in 2018.

The number of languages into which the Bible has been translated has grown exponentially during the past 2300 years. The history of Bible translation can be divided into three periods of growth, each with its distinct limiting and driving forces. In the low-growth period between 260 BC and 1814 growth was constrained by the rise of Islam and later by the information monopoly of the Catholic Church. The year 1815 was the inflection point, at which annual growth rates rose from below one to above one percent. The century 1815–1914 was a period of substantial growth due to the co-occurrence of three driving forces: Christian revivalism, internationalization, and industrialization. This was followed by a third period—the era of explosive growth between 1915 and today—in which information technology and the organizational structure of translation agencies have spurred growth. An array of multinational organizations of Anglo-Saxon origin have created a quasi-monopoly for worldwide Bible translation. The exponential growth of worldwide Bible translation can be modeled by a mathematical function. Using this function and assuming the continuation of current trends, it is possible to project the end of the history of pioneer Bible translation sometime between 2026 and 2031.

The Phenomenon

In a complex system, an entity is regarded as growing exponentially if its quantity increases by a factor of more than one over a given time interval. For example, annual compounded interest of more than 1% on capital invested in a bank account will cause the amount to grow exponentially. Self-reproducing organisms, from bacteria to humans, have the potential for exponential growth. In the same way, industrial capital such as machinery may follow an exponential path by virtue of the fact that machines are used to produce new machines. System theorists like MeadowsSee Meadows D.,J. Randers and D. Meadows, 2004, Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company. and her colleagues call the growth of self-replicating entities “inherent exponential growth.” The growth of non-self-replicating entities may also be exponential, if these depend on a self-replicating entity. This second type of growth is called “derived exponential growth.” Food production and resource use, for instance, are driven by human population growth and may rise (and indeed have risen) exponentially.

In a complex system, an entity is regarded as growing exponentially if its quantity increases by a factor of more than one over a given time interval. For example, annual compounded interest of more than 1% on capital invested in a bank account will cause the amount to grow exponentially. Self-reproducing organisms, from bacteria to humans, have the potential for exponential growth. In the same way, industrial capital such as machinery may follow an exponential path by virtue of the fact that machines are used to produce new machines. System theorists like MeadowsSee Meadows D.,J. Randers and D. Meadows, 2004, Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company. and her colleagues call the growth of self-replicating entities “inherent exponential growth.” The growth of non-self-replicating entities may also be exponential, if these depend on a self-replicating entity. This second type of growth is called “derived exponential growth.” Food production and resource use, for instance, are driven by human population growth and may rise (and indeed have risen) exponentially.

The question of whether the number of human languages, currently at around 7,000, has increased exponentially over thousands of years has no definite answer. The historical linguist Trask seems to argue against exponential growth.  He dates any increase in the number of languages back to human prehistory. After the initial peopling of our planet, the total number of languages would have remained constant, at roughly “between 5000 and 10000See Trask, R. L. (1996). Historical Linguistics. London: Edward Arnolds Publishers, p. 325.”. A mathematical model of the growth pattern in human languages would require the dating and counting of hundreds of proto-languages, which is an endeavor on which linguists gave up some time agoIn 1895, the Bulletin de la Société Linguistique de Paris announced that it would reject any paper that attempted to reconstruct the ancestor language of all human languages.. Theoretically speaking, it is possible for the number of human languages to grow exponentially, as such growth depends on populations and their actions. As human populations expand and migrate to new areas, spatial separation causes the speech patterns of two or more communities to change in different ways. The accumulated changes result in different dialects, and ultimately in mutually unintelligible languages. Additionally, new languages may be formed by the process of creolization in which two languages merge into a hybrid language. Thus, the potential for exponential growth does exist, but the actual growth pattern of human languages is notoriously difficult to establish.

He dates any increase in the number of languages back to human prehistory. After the initial peopling of our planet, the total number of languages would have remained constant, at roughly “between 5000 and 10000See Trask, R. L. (1996). Historical Linguistics. London: Edward Arnolds Publishers, p. 325.”. A mathematical model of the growth pattern in human languages would require the dating and counting of hundreds of proto-languages, which is an endeavor on which linguists gave up some time agoIn 1895, the Bulletin de la Société Linguistique de Paris announced that it would reject any paper that attempted to reconstruct the ancestor language of all human languages.. Theoretically speaking, it is possible for the number of human languages to grow exponentially, as such growth depends on populations and their actions. As human populations expand and migrate to new areas, spatial separation causes the speech patterns of two or more communities to change in different ways. The accumulated changes result in different dialects, and ultimately in mutually unintelligible languages. Additionally, new languages may be formed by the process of creolization in which two languages merge into a hybrid language. Thus, the potential for exponential growth does exist, but the actual growth pattern of human languages is notoriously difficult to establish.

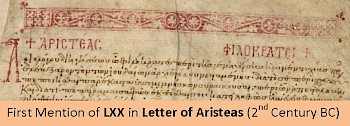

The number of languages for which a translation of the Bible, in whole or in part, is available, on the other hand, has risen exponentially, as we demonstrate in this section. The canon of the Bible was formed after the number of languages on Earth had stabilized.  The first attested translation of ScripturesWe employ the term Scriptures in this paper as a shorthand for ”translated Bible portions”.was the Septuagint. The ancient historian Josephus links the Thora portion of the Septuagint to the year 260 BC. According to our own count, the total number of languages into which Scriptures have been translated reached the 2850 mark in 2013. This enumeration is based on a particular definition of what constitutes a human language, namely that reflected by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in Geneva, Switzerland. The ISO 639-3 standardThe registration authority of ISO 639-3 is the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), a missionary organization. The ISO 639-3 standard grew out of the list of codes established in the Ethnologue (Lewis et al., 2016), the flagship publication of SIL. Ethnologue appeared first in 1951 and its 22nd edition was published in 2019. is a registry of 7,881 language codes and language names published in 2007. The registry represents each language by a unique three-letter code (e.g. “eng” for English; “yor” for Yoruba).

The first attested translation of ScripturesWe employ the term Scriptures in this paper as a shorthand for ”translated Bible portions”.was the Septuagint. The ancient historian Josephus links the Thora portion of the Septuagint to the year 260 BC. According to our own count, the total number of languages into which Scriptures have been translated reached the 2850 mark in 2013. This enumeration is based on a particular definition of what constitutes a human language, namely that reflected by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in Geneva, Switzerland. The ISO 639-3 standardThe registration authority of ISO 639-3 is the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), a missionary organization. The ISO 639-3 standard grew out of the list of codes established in the Ethnologue (Lewis et al., 2016), the flagship publication of SIL. Ethnologue appeared first in 1951 and its 22nd edition was published in 2019. is a registry of 7,881 language codes and language names published in 2007. The registry represents each language by a unique three-letter code (e.g. “eng” for English; “yor” for Yoruba).

|

Category |

Languages (ISO 639-3) |

|---|---|

|

Extinct |

814 |

|

Existing |

7,046 |

|

Constructed |

21 |

|

Total |

7,881 |

|

Translations (2013) |

2,850 |

|

|

|

Table 1: Languages per category

|

Continent |

Languages (ISO 639-3) |

|---|---|

|

Africa |

2,250 |

|

Americas |

1,198 |

|

Asia |

2,514 |

|

Europe |

378 |

|

Oceania |

1,534 |

|

Total |

7,881 |

Table 2: Languages per continent

Some linguists have criticized the ISO 639-3 standard, even going so far as to question its usefulness. We argue that the case for a language identification system can be made and that its benefits greatly outweigh any deficiencies. A summary of this debate is provided in the Appendix.

We compiled the dates of Scripture translations from various sources, for example from web-searches and from publications of the United Bible Societies (UBS): The Book of a Thousand Tongues (1st edition by North, 1938; 2nd edition by Nida, 1972), Scriptures of the World (the editions of 1968 and 1996), and the Scriptures Language Reports (1991–today). We also used information included in the Ethnologue of the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) and obtained in personal communication. Although these datasets overlap, each has translation dates contradicting the others or not reported by the others. To the best of my knowledge, these datasets have never been integrated before. The growth curves for different Scripture categories are displayed in Chart 1.

The yellow curve, representing the cumulative number of translations, has the hockey stick shape characteristic of exponential curves. The process of Scripture translation has inherent exponential growth, not derived from anything that grows exponentially. It is self-replicating by virtue of the fact that translations are used to produce other translationsFor example, the Syriac Peshitta was used in the translation of the Armenian Bible; the Peshitta and Armenian Bible were then used in the translation of the Georgian Bible.. The red dashed line is a mathematical model of the growth curve for which we calculate the formula in section 4. An important paradigm shift occurred between 1789 and 1830 that pushed the annual growth rate from below one percent to above one percent, with the year 1815 marking the inflection point of the exponential curve. In section 3, we identify three enabling factors for this paradigm shift that are still at work today. Chart 2 magnifies the data for the last 200 years, showing an explosive and ever-accelerating rate of growth.

System theoristsSee Meadows D.,J. Randers and D. Meadows, 2004, Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company, p. 31. have described exponential processes in terms of positive and negative feedback loops. A feedback loop is a chain of cause-and-effect relationships resulting in changes of the original base. A positive feedback loop produces runaway growth, while a negative feedback loop keeps growth in check, holding the total quantity within a certain range. The translation of Scripture into new languages, including its enabling factors, forms the positive feedback loop of the current stock of Bibles. Bible versions that are not updated and drop out of use form the negative feedback loop. In the 19th century, for example, Bibles were translated into several Chinese dialects that European standards regard as unintelligible languages. With the rise of Mandarin Chinese in the 20th century, the Mandarin Bible supplanted most dialect versions.

Enabling Factors

The history of worldwide Bible translation can be divided into three eras: a period of low growth (260 BC–1814 AD); a period of sustained high growth (1815–1914); and a period of explosive growth (1915–today). The years between 1789 and 1830 constitute a time window for a paradigm shift that enabled the rapid growth of the latter two eras.

Low growth (260 BC–1814 AD): Ancient geopolitics constrained the growth of the number of  languages with Scriptures over the 2074 years following the Septuagint. Before the seventh century AD, transcontinental trade routes were under Roman control or were decentralized. After the seventh century, Islamic polities checked all major trade routes and confined Christianity to Western Europe as the only region in which it developed majority status. Before the rise of Islam, Bible portions were translated into 11 ancient languages, all scattered along major trade routes. On the most important trade track, the Silk Road, translators produced Scriptures in the following languages (from west to east): AramicWhen the Jews returned from the Babylonian exile around the year 532 BC, they spoke Aramaic, the official language of the Babylonian Empire, not their ancestral Hebrew language. They needed an interpretation when they listened to the Hebrew Bible (see Nehemia 8:7–8). This translation into Aramaic, called Targum, was initially oral and was written down later, probably starting around the year 120 BC. After the dissolution of the Babylonian empire, the Aramaic language broke into Western and Eastern dialects that quickly developed into two unintelligible languages and then into two groups of dialects. Jewish Palestinian Aramaic in which the Targum was written is an Eastern Aramaic language. (120 BC?), Old SyriacOld Syriac or Classical Syriac was the Eastern Aramaic language spoken in Edessa, modern-day Şanlıurfa in Turkey, from 100 BC to 1400 AD. Portions of the Old and New Testament were completed by unknown translators as early as 110 AD. The New Testament is mentioned for the first time in 160 AD. The Syriac Bible, called Peshitta, became the standard version of the Syrian Orthodox Church in the fifth century. The Peshitta formed the basis for all translations into languages spoken along the Silk Road. (110 AD?), ArmenianThe conversion of the Armenians to Christianity in 301 AD is attributed to Gregory the Illuminator, who was consecrated as the first Catholicos of the Armenian Church. In 406, the Armenian linguist Mesrob Mashtots created the Armenian script, and in 411 he and Catholicos Sahak translated the Classical Armenian Bible, basing their translation on the Peshitta. After accessing the Septuagint and the Greek New Testament, they revised the whole Bible in 434. (411), GeorgianAccording to Christian tradition, the Georgians accepted the Christian faith in the early fourth century because of St. Nino, a slave woman. The Bible was translated into Old or Classical Georgian using a special alphabet that was reformed later in the 11th century. The earliest Bible manuscripts date from the fifth century and show that both the Syriac Peshitta Bible and the Armenian Bible were used as the basis for translation (see Songulashvili, 1990). (480?), Middle PersianMiddle Persian or Pahlavi (Indo-European language family) was spoken in the Sasanian kingdom from 300 BC to 800 AD. After the ninth century, Pahlavi survived as the liturgical language used by Zoroastrian priests. The only extant Bible fragments in Pahlavi are Psalms 94–99, 118, and 121–36, which were discovered in the ruins of the Nestorian monastery in Bulayïq near Turfan (China). The Babylonian Talmud (Megillah Tractate 18a) alludes to the Elamite and Median languages in which it was permitted to recite the Book of Esther on the Day of Purim. One of these languages probably refers to the Pahlavi language, suggesting that the Book of Esther too was translated into Middle Persian (Andreas, 1910; Sundermann, 1989, p. 138). (550?), SogdianThe Sogdian language was the lingua franca used on the Silk Road during the Táng dynasty 唐朝 (618–907). It is an Indo-European language spoken around Samarkand, Uzbekistan, from 100 BC to 1000 AD. The modern Yaghnobi language, native to 12,000 people in Tajikistan, descends directly from Sogdian. The Sogdian people in Samarkand were supplanted by Uzbek and Tajik tribes in the 16th century. Fragments of the Sogdian Psalter and of the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John were discovered in the ruins of the Nestorian monastery in Bulayïq near Turfan (see Peters, 1936, and Schwartz, 1974). (380?), and Middle ChineseMiddle Chinese was the vehicular language of the Táng dynasty and spoken during the period 0–900 AD. In 1625, a stela was excavated in the city of Xī'ān, the former capital of the Táng dynasty, and is now held at the Xī'ān Bēilín Museum 西安碑林. The Chinese text on the stela mentions the arrival of Nestorian missionaries in 635 and the translation of Bible portions, none of which survive. Horne (1917) translated the text of the stela into English (available online). (650?). On the eastern track of the Trans-Saharan Trade RoutesEric Ross (2011) presents the historical trans-Saharan trade relations as a network of trade routes spanning the whole Saharan desert., Bible portions were translated in two languages: CopticChristians were present in Egypt possibly since the time of the New Testament. Apollos, a coworker of the apostle Paul, was a Jewish Christian from Alexandria (see Acts 18:24–25). Wisse (1995) dates the first Scripture translated into the Sahidic dialect of Coptic back to the year 400. When Alexandria was conquered by Islamic forces in 642, Christians gradually moved to Upper Egypt. A new Coptic version of the Bible in the Bohairic dialect was needed and completed by the year 800. (400) in the north and Ge'ezGe'ez (or Ethiopian), a Semitic language of the Afro-Asiatic family, was the official language of the Aksum kingdom in Ethiopia during the period 100–940 AD. According to tradition, the Syrian-Greek missionary Frumentius converted Ezana, king of Ethiopia, to Christianity in 383. The exact date and sources of the Ge'ez Bible are uncertain. A number of Syrian missionaries moved to Ethiopia in the fifth century, suggesting that the Peshitta might have been the source, but specialists relate most of the Ge'ez Bible to the Septuagint and to the Greek New Testament. Since the 10th century, Ge'ez has been used as a liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. See Mikre-Sellasie (2000) and Zuurmond (1995) for details. (480?) in the south. Rome, the home of the Latin VulgateHieronymus was the only translator of the Latin Vulgate Bible completed in 405. He spent considerable time in Bethlehem to access the original Hebrew text. (405), was reached from the Middle East via the Mediterranean Trade Routes, and GothicGothic was an Eastern Germanic language that became extinct before the ninth century. The Goths populated the areas of Bulgaria and Ukraine where they were reached by missionaries in the mid-third century. The conversion of the Goths is generally attributed to Wulfila (311–382), who was consecrated as Bishop of the Goths in 342. Wulfila created the Gothic alphabet and translated the Bible. A few manuscripts survive, of which the Codex Argenteus now conserved at the University of Uppsala is the most famous. The University of Antwerp hosts the Wulfila online project with various Gothic language resources (see Rhodes, 2007, pp. 101–102). (350?) was attained from Cappadocia.

languages with Scriptures over the 2074 years following the Septuagint. Before the seventh century AD, transcontinental trade routes were under Roman control or were decentralized. After the seventh century, Islamic polities checked all major trade routes and confined Christianity to Western Europe as the only region in which it developed majority status. Before the rise of Islam, Bible portions were translated into 11 ancient languages, all scattered along major trade routes. On the most important trade track, the Silk Road, translators produced Scriptures in the following languages (from west to east): AramicWhen the Jews returned from the Babylonian exile around the year 532 BC, they spoke Aramaic, the official language of the Babylonian Empire, not their ancestral Hebrew language. They needed an interpretation when they listened to the Hebrew Bible (see Nehemia 8:7–8). This translation into Aramaic, called Targum, was initially oral and was written down later, probably starting around the year 120 BC. After the dissolution of the Babylonian empire, the Aramaic language broke into Western and Eastern dialects that quickly developed into two unintelligible languages and then into two groups of dialects. Jewish Palestinian Aramaic in which the Targum was written is an Eastern Aramaic language. (120 BC?), Old SyriacOld Syriac or Classical Syriac was the Eastern Aramaic language spoken in Edessa, modern-day Şanlıurfa in Turkey, from 100 BC to 1400 AD. Portions of the Old and New Testament were completed by unknown translators as early as 110 AD. The New Testament is mentioned for the first time in 160 AD. The Syriac Bible, called Peshitta, became the standard version of the Syrian Orthodox Church in the fifth century. The Peshitta formed the basis for all translations into languages spoken along the Silk Road. (110 AD?), ArmenianThe conversion of the Armenians to Christianity in 301 AD is attributed to Gregory the Illuminator, who was consecrated as the first Catholicos of the Armenian Church. In 406, the Armenian linguist Mesrob Mashtots created the Armenian script, and in 411 he and Catholicos Sahak translated the Classical Armenian Bible, basing their translation on the Peshitta. After accessing the Septuagint and the Greek New Testament, they revised the whole Bible in 434. (411), GeorgianAccording to Christian tradition, the Georgians accepted the Christian faith in the early fourth century because of St. Nino, a slave woman. The Bible was translated into Old or Classical Georgian using a special alphabet that was reformed later in the 11th century. The earliest Bible manuscripts date from the fifth century and show that both the Syriac Peshitta Bible and the Armenian Bible were used as the basis for translation (see Songulashvili, 1990). (480?), Middle PersianMiddle Persian or Pahlavi (Indo-European language family) was spoken in the Sasanian kingdom from 300 BC to 800 AD. After the ninth century, Pahlavi survived as the liturgical language used by Zoroastrian priests. The only extant Bible fragments in Pahlavi are Psalms 94–99, 118, and 121–36, which were discovered in the ruins of the Nestorian monastery in Bulayïq near Turfan (China). The Babylonian Talmud (Megillah Tractate 18a) alludes to the Elamite and Median languages in which it was permitted to recite the Book of Esther on the Day of Purim. One of these languages probably refers to the Pahlavi language, suggesting that the Book of Esther too was translated into Middle Persian (Andreas, 1910; Sundermann, 1989, p. 138). (550?), SogdianThe Sogdian language was the lingua franca used on the Silk Road during the Táng dynasty 唐朝 (618–907). It is an Indo-European language spoken around Samarkand, Uzbekistan, from 100 BC to 1000 AD. The modern Yaghnobi language, native to 12,000 people in Tajikistan, descends directly from Sogdian. The Sogdian people in Samarkand were supplanted by Uzbek and Tajik tribes in the 16th century. Fragments of the Sogdian Psalter and of the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John were discovered in the ruins of the Nestorian monastery in Bulayïq near Turfan (see Peters, 1936, and Schwartz, 1974). (380?), and Middle ChineseMiddle Chinese was the vehicular language of the Táng dynasty and spoken during the period 0–900 AD. In 1625, a stela was excavated in the city of Xī'ān, the former capital of the Táng dynasty, and is now held at the Xī'ān Bēilín Museum 西安碑林. The Chinese text on the stela mentions the arrival of Nestorian missionaries in 635 and the translation of Bible portions, none of which survive. Horne (1917) translated the text of the stela into English (available online). (650?). On the eastern track of the Trans-Saharan Trade RoutesEric Ross (2011) presents the historical trans-Saharan trade relations as a network of trade routes spanning the whole Saharan desert., Bible portions were translated in two languages: CopticChristians were present in Egypt possibly since the time of the New Testament. Apollos, a coworker of the apostle Paul, was a Jewish Christian from Alexandria (see Acts 18:24–25). Wisse (1995) dates the first Scripture translated into the Sahidic dialect of Coptic back to the year 400. When Alexandria was conquered by Islamic forces in 642, Christians gradually moved to Upper Egypt. A new Coptic version of the Bible in the Bohairic dialect was needed and completed by the year 800. (400) in the north and Ge'ezGe'ez (or Ethiopian), a Semitic language of the Afro-Asiatic family, was the official language of the Aksum kingdom in Ethiopia during the period 100–940 AD. According to tradition, the Syrian-Greek missionary Frumentius converted Ezana, king of Ethiopia, to Christianity in 383. The exact date and sources of the Ge'ez Bible are uncertain. A number of Syrian missionaries moved to Ethiopia in the fifth century, suggesting that the Peshitta might have been the source, but specialists relate most of the Ge'ez Bible to the Septuagint and to the Greek New Testament. Since the 10th century, Ge'ez has been used as a liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. See Mikre-Sellasie (2000) and Zuurmond (1995) for details. (480?) in the south. Rome, the home of the Latin VulgateHieronymus was the only translator of the Latin Vulgate Bible completed in 405. He spent considerable time in Bethlehem to access the original Hebrew text. (405), was reached from the Middle East via the Mediterranean Trade Routes, and GothicGothic was an Eastern Germanic language that became extinct before the ninth century. The Goths populated the areas of Bulgaria and Ukraine where they were reached by missionaries in the mid-third century. The conversion of the Goths is generally attributed to Wulfila (311–382), who was consecrated as Bishop of the Goths in 342. Wulfila created the Gothic alphabet and translated the Bible. A few manuscripts survive, of which the Codex Argenteus now conserved at the University of Uppsala is the most famous. The University of Antwerp hosts the Wulfila online project with various Gothic language resources (see Rhodes, 2007, pp. 101–102). (350?) was attained from Cappadocia.

After the Islamic conquests and during the Islamic Golden Age (650–1300), Eastern Christianity was marginalized in its own territory and the supply of missionaries and translators dried up. Travel along the trade routes was unsafe for Christians. Except for one Asian language, the only region in which Scriptures were translated between 650 and 1400 was Europe with 10 new languagesThe 10 European languages in chronological order are the following: Mondsee Gospel in Old High German (810); Vespasian Psalter in Old English (850); Methodius Bible in Church Slavonic (884); Stjórn Old Testament in Old Norse (1205?); Waldensian New Testament in Old Provençal (1190?); Alfonso Bible in Spanish (1280); Bible Historiale in Old French (1297); Augsburg New Testament in Middle High German (1350); Herne Bible in Middle Dutch (1360); Wycliffe Bible in Middle English (1384). Furthermore, in 1307 the Catholic papal envoy to the Mongol court, John of Montecorvino, translated the New Testament into the Old Uyghur, the lingua franca of the Mongol elite in China. No manuscript has been preserved, but John reported his achievement in letters to the Pope (see Yule, 1914, pp. 45–58).. For three hundred years (900–1200), translation projects were frozen without any known output of Scriptures. Three factors explain this inactivity.  First, Europe was linguistically fragmented with hundreds of vernacular languages that had proliferated after the fall of the Roman Empire. These vernacular languages showed extensive regional variation, making communication impossible between people living more than 300 kmSee Trask, R. L., 1996. Historical Linguistics. London: Edward Arnolds Publishers, pp. 165–169. apart. The sovereign of each polity represented one language variety but did not promote this variety with a consistent language policy.

First, Europe was linguistically fragmented with hundreds of vernacular languages that had proliferated after the fall of the Roman Empire. These vernacular languages showed extensive regional variation, making communication impossible between people living more than 300 kmSee Trask, R. L., 1996. Historical Linguistics. London: Edward Arnolds Publishers, pp. 165–169. apart. The sovereign of each polity represented one language variety but did not promote this variety with a consistent language policy.

Most languages did not exhibit a single obvious variety upon which a translation could be based. Second, the Popes developed a negative attitude toward translating the Vulgate into the vernacular languages of Europe that culminated in prohibitions, at the Councils of Toulouse (1229)This prohibition is included in Canon 14 of the Council of Toulouse of 1229 (see Peters, 1980, p. 195). and Tarragona (1234)This prohibition is included in Canon 2 of the Council of Tarragona of 1234 (see Simms, 1929, p. 162)., against reading and translating the Scriptures.  Third, the intellectual climate at the turn of the first Millennium was not conducive to major endeavors such as Bible translation. The information monopolyThe information network of the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages consisted of three levels (Dudley 1991, p. 146; Hanson, 2008, p. 14): At the top tier the Pope and his high-ranking cardinals decided on the type of information the European public was allowed to know. In the second tier were monasteries, seminaries, and later universities that received, archived, and transmitted this information in Medieval Latin to the literate elite. At the third level was this elite, consisting mainly of priests educated in Latin, who translated the information into the vernacular languages of Europe to make it available to the illiterate masses. of the Catholic Church, the corruption of the PopesBetween 924 and 1048, the Roman popes were installed and controlled by two factions of a Roman noble clan, the Tusculans and Crescentii, both consisting of descendants of Theophylact (864–924), a high curial officer. Theophylact‘s wife and daughter influenced the appointment of popes between 924 and 974. The Crescentii installed their popes between 974 and 1012 and the Tusculans theirs between 1012 and 1048, before the German king Henry III finished their scheme (Cushing, 2005, pp. 61–62). The 124 years between 924 and 1048 have been called the Dark Age by Catholic Church historians since the 16th century (Dwyer, 1998, p. 155)., and, as some have argued, apocalypticism of the year 1000The Book of Revelation 20:3–5 teaches that the last judgment will occur after a period of 1000 years in which the devil is held in captivity. In a certain version of the post-millenarist doctrine, the year 1000 was the earliest point in time that the last judgment could have occurred. Burr (1901) summarized the view of European historians that the year 1000 had not generated any apocalyptic fervor, while Landes (2000), one hundred years later, defended the existence of end-time expectations in the run-up to the year 1000. held intellectual activity in bondage.

Third, the intellectual climate at the turn of the first Millennium was not conducive to major endeavors such as Bible translation. The information monopolyThe information network of the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages consisted of three levels (Dudley 1991, p. 146; Hanson, 2008, p. 14): At the top tier the Pope and his high-ranking cardinals decided on the type of information the European public was allowed to know. In the second tier were monasteries, seminaries, and later universities that received, archived, and transmitted this information in Medieval Latin to the literate elite. At the third level was this elite, consisting mainly of priests educated in Latin, who translated the information into the vernacular languages of Europe to make it available to the illiterate masses. of the Catholic Church, the corruption of the PopesBetween 924 and 1048, the Roman popes were installed and controlled by two factions of a Roman noble clan, the Tusculans and Crescentii, both consisting of descendants of Theophylact (864–924), a high curial officer. Theophylact‘s wife and daughter influenced the appointment of popes between 924 and 974. The Crescentii installed their popes between 974 and 1012 and the Tusculans theirs between 1012 and 1048, before the German king Henry III finished their scheme (Cushing, 2005, pp. 61–62). The 124 years between 924 and 1048 have been called the Dark Age by Catholic Church historians since the 16th century (Dwyer, 1998, p. 155)., and, as some have argued, apocalypticism of the year 1000The Book of Revelation 20:3–5 teaches that the last judgment will occur after a period of 1000 years in which the devil is held in captivity. In a certain version of the post-millenarist doctrine, the year 1000 was the earliest point in time that the last judgment could have occurred. Burr (1901) summarized the view of European historians that the year 1000 had not generated any apocalyptic fervor, while Landes (2000), one hundred years later, defended the existence of end-time expectations in the run-up to the year 1000. held intellectual activity in bondage.

In the age of scholasticism, critical thinking was gradually (re)introduced, but this did not substantially increase the number of Scripture translations, at least not between 1200 and 1400. In six out of eight new languages, local authorities or kings sponsored the translation For example, the Stjórn translation of the Old Testament into Old Norse was supported at some point by the king of Norway (see Kirby 1986, 1993)., while in two languages (Old Occitan and Middle English) the establishment repressed the translatorsThe Waldensians, a Christian movement that was founded by Peter Waldo and violently suppressed by the Catholic Church, translated the New Testament into Old Occitan/Provençal around 1190 (see Tourn, 1980). John Wycliffe, the translator of the Bible into Middle English, was a dissident Catholic priest who is viewed today as a precursor of the English Reformation.. These translators represented the first challenge to the information monopoly of the Catholic Church.

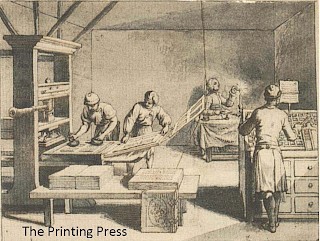

Two pivotal events made an impact on the history of Bible translation: the invention of the printing press by Johann Gutenberg in 1455 and the discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492. The emergence of the printing press undermined the information monopoly of the Catholic Church in two ways. Firstly, it enabled Martin Luther and other Reformers to disseminate their views by circumventing the censorship of the Catholic Church (Hanson, 2008, p. 15). Secondly, the printing press signaled a move away from Latin toward vernacular languages.  Although the first printed book was the Vulgate, a stream of printed Bibles in 25 European and five Asian languagesToscana Italian (1471); Catalan (1478); Middle Low German (1478); Middle French (1487); Czech (1488); Portuguese (1505); South Levantine Arabic (1517); Belarusian (1517); Modern Spanish (1517); Modern High German (1522); Polish (1522); Danish (1524); Modern Dutch (1526); Modern English (1526); Swedish (1526); Hungarian (1533); Icelandic (1540); Western Yiddish (1544); Western Farsi (1546); Modern Greek (1547); Ladino (1547); Finnish (1548); Romanian (1553); Slovenian (1555); Romansch (1560); Waldensian Vaudois (1560); Croatian (1562); Ottoman Turkish (1565); Welsh (1567); Basque (1571). followed suit in the 15th and 16th centuries. These vernacular Bible translations initiated different processes of language standardization driven by the printing press. Since Latin was only available to a minority of intellectuals, printers and booksellers actively created a market for books in vernacular languages by shaping standard language varietiesAt an early stage, printers undertook the task of standardization. For example, the English printer William Caxton (1422–1491) chose words in his publications that had widest circulation in different British dialects (Trask, 1996, p. 166); in Germany, a similar role was played by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) who printed pamphlets for Martin Luther. that would be comprehensible to a wide readership. Benedict AndersonSee Anderson, Benedict (1991). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso. called the commercial interest of printers the “logic of print capitalism,” which dictated that more books be printed in the speech of ordinary people.

Although the first printed book was the Vulgate, a stream of printed Bibles in 25 European and five Asian languagesToscana Italian (1471); Catalan (1478); Middle Low German (1478); Middle French (1487); Czech (1488); Portuguese (1505); South Levantine Arabic (1517); Belarusian (1517); Modern Spanish (1517); Modern High German (1522); Polish (1522); Danish (1524); Modern Dutch (1526); Modern English (1526); Swedish (1526); Hungarian (1533); Icelandic (1540); Western Yiddish (1544); Western Farsi (1546); Modern Greek (1547); Ladino (1547); Finnish (1548); Romanian (1553); Slovenian (1555); Romansch (1560); Waldensian Vaudois (1560); Croatian (1562); Ottoman Turkish (1565); Welsh (1567); Basque (1571). followed suit in the 15th and 16th centuries. These vernacular Bible translations initiated different processes of language standardization driven by the printing press. Since Latin was only available to a minority of intellectuals, printers and booksellers actively created a market for books in vernacular languages by shaping standard language varietiesAt an early stage, printers undertook the task of standardization. For example, the English printer William Caxton (1422–1491) chose words in his publications that had widest circulation in different British dialects (Trask, 1996, p. 166); in Germany, a similar role was played by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) who printed pamphlets for Martin Luther. that would be comprehensible to a wide readership. Benedict AndersonSee Anderson, Benedict (1991). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso. called the commercial interest of printers the “logic of print capitalism,” which dictated that more books be printed in the speech of ordinary people.

The discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492 inaugurated a period of exploration, conquest, and colonization and led to the rise of global trade. It put an end to European isolation by Islamic polities that had dominated strategic parts of the Old World (Europe, Africa, and Asia) for centuries. Nevertheless, it took over 300 years before the end of European isolation led to a substantial increase in translated Bibles.  Between 1600 and 1814, Scriptures were translated into approximately 40 new languagesIrish (1602); Lithuanian (1625); Malay (1629); Samaritan (1632); Latvian (1637); Sami (1648); Wampanoag (1655); Nogai (1659); Siraya (1661); Modern French (1667); Upper Sorbian (1670); Vlaxian Romani (1670); Estonian (1686); Võro (1686); Lower Sorbian (1709); Tamil (1714); Sinhala (1739); Modern Georgian (1743); Inuit (1744); Deccan (1747); Manx (1748); Western Frisian (1755); Gaelic (1767); Berbice Creole Dutch (1781); Negerhollands (1781); Modern Turkish (1782); Mohawk (1787); Bengali (1800); Bosnian (1804); Urdu (1805); Hindi (1806); Marathi (1807); Sanskrit (1808); Gujarati (1809); Odia (1809); Labrador Eskimo (1810); Classical Chinese (1810); Malayalam (1811); Telugu (1812); Kannada (1812)., nearly the same quantity (30 languages) as in the period 1400–1600. This low growth is due to the fact that the early discoveries were made by Catholic nations that operated under the information monopoly of the Catholic Church. In response to the challenges of the Reformation, the Council of Trent (1545–1563) restated the importance of the Bible and made the Vulgate the official Catholic Bible, but remained neutralSee Bedouelle, G. (1989). “La réforme catholique”, in Le temps des Réformes et la Bible, edited by G. Bedouelle and B. Roussel, pp. 327–368. Paris: Éditions Beauchesne. on the issue of vernacular translations. Pope Gregory XV founded the Propaganda FideThe full name is Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (“Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith”). Pope John Paul II changed its name to Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples in 1982. in 1622 with the aim of bringing all Catholic missionaries under one unified administration. In 1655, the Propaganda Fide prohibited by decree the publication of books by missionaries without prior permission. This decree made Bible versions in vernacular languages almost impossibleSee Kowalsky, N. (1966). “Die Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide und die Übersetzung der Heiligen Schrift”, in Die Heilige Schrift in den katholischen Missionen, edited by J. Beckmann. Beckenried, Switzerland: Schöneck.. Requests made by Catholic missionaries to publish vernacular translations were routinely turned down, which resulted in a number of aborted projects and unpublished Bible versionsThis happened, for example, to the Missions Etrangères de Paris in 1670, which requested permission to translate the Bible into Chinese but was refused in 1673 (Kowalsky, 1966, pp. 31–32). When Father Jean Basset died in 1707, he had translated 80% of the New Testament into Chinese, but his version was not authorized for publication (Standaert, 1999, pp. 31–38). There are also reports of a New Testament translated into Japanese by Jesuits in 1613, but no copy survived as it does not appear to have been published (Soesilo, 2007, p. 164).. The only new languages into which Scriptures were translated between 1600 and 1814 were either (smaller) European languages or languages in America or Asia reached by the nascent Protestant missionsThe first language of the New World into which Scriptures were translated was Wampanoag, an Algonquian language spoken in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. The Puritan missionary John Elliot translated the whole Bible between 1655 and 1663. Albert Cornelisz Ruyl of the Dutch East Indies Company translated the Gospel of Matthew into Malay in 1629, which was the first portion of the Bible completed in an Asian language in early modern times. This translation was commissioned by the Dutch Reformed Church..

Between 1600 and 1814, Scriptures were translated into approximately 40 new languagesIrish (1602); Lithuanian (1625); Malay (1629); Samaritan (1632); Latvian (1637); Sami (1648); Wampanoag (1655); Nogai (1659); Siraya (1661); Modern French (1667); Upper Sorbian (1670); Vlaxian Romani (1670); Estonian (1686); Võro (1686); Lower Sorbian (1709); Tamil (1714); Sinhala (1739); Modern Georgian (1743); Inuit (1744); Deccan (1747); Manx (1748); Western Frisian (1755); Gaelic (1767); Berbice Creole Dutch (1781); Negerhollands (1781); Modern Turkish (1782); Mohawk (1787); Bengali (1800); Bosnian (1804); Urdu (1805); Hindi (1806); Marathi (1807); Sanskrit (1808); Gujarati (1809); Odia (1809); Labrador Eskimo (1810); Classical Chinese (1810); Malayalam (1811); Telugu (1812); Kannada (1812)., nearly the same quantity (30 languages) as in the period 1400–1600. This low growth is due to the fact that the early discoveries were made by Catholic nations that operated under the information monopoly of the Catholic Church. In response to the challenges of the Reformation, the Council of Trent (1545–1563) restated the importance of the Bible and made the Vulgate the official Catholic Bible, but remained neutralSee Bedouelle, G. (1989). “La réforme catholique”, in Le temps des Réformes et la Bible, edited by G. Bedouelle and B. Roussel, pp. 327–368. Paris: Éditions Beauchesne. on the issue of vernacular translations. Pope Gregory XV founded the Propaganda FideThe full name is Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (“Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith”). Pope John Paul II changed its name to Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples in 1982. in 1622 with the aim of bringing all Catholic missionaries under one unified administration. In 1655, the Propaganda Fide prohibited by decree the publication of books by missionaries without prior permission. This decree made Bible versions in vernacular languages almost impossibleSee Kowalsky, N. (1966). “Die Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide und die Übersetzung der Heiligen Schrift”, in Die Heilige Schrift in den katholischen Missionen, edited by J. Beckmann. Beckenried, Switzerland: Schöneck.. Requests made by Catholic missionaries to publish vernacular translations were routinely turned down, which resulted in a number of aborted projects and unpublished Bible versionsThis happened, for example, to the Missions Etrangères de Paris in 1670, which requested permission to translate the Bible into Chinese but was refused in 1673 (Kowalsky, 1966, pp. 31–32). When Father Jean Basset died in 1707, he had translated 80% of the New Testament into Chinese, but his version was not authorized for publication (Standaert, 1999, pp. 31–38). There are also reports of a New Testament translated into Japanese by Jesuits in 1613, but no copy survived as it does not appear to have been published (Soesilo, 2007, p. 164).. The only new languages into which Scriptures were translated between 1600 and 1814 were either (smaller) European languages or languages in America or Asia reached by the nascent Protestant missionsThe first language of the New World into which Scriptures were translated was Wampanoag, an Algonquian language spoken in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. The Puritan missionary John Elliot translated the whole Bible between 1655 and 1663. Albert Cornelisz Ruyl of the Dutch East Indies Company translated the Gospel of Matthew into Malay in 1629, which was the first portion of the Bible completed in an Asian language in early modern times. This translation was commissioned by the Dutch Reformed Church..

|

Interval |

Africa |

Americas |

Asia |

Europe |

Oceania |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

260 BC-0 AD |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

0-200 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

200-400 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

|

400-600 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

|

600-800 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

800-1000 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

|

1000-1200 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1200-1400 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

0 |

8 |

|

1400-1600 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

25 |

0 |

30 |

|

1600-1814 |

0 |

7 |

18 |

15 |

0 |

40 |

|

Total |

2 |

7 |

32 |

53 |

0 |

94 |

Table 3: Translations of Scriptures before 1815

The inflection point in the history of worldwide Bible translation occurred in the year 1815 when eight new languages were added to the set of languages with Scriptures. Starting from that year, annual growth rates were constantly above one percent.

The paradigm shift (1789–1830): The inflection point from low to high growth in Bible translation is due to the co-occurrence of three factors: Christian revivalism, internationalization, and industrialization. The nations that contributed most to worldwide Bible translation in the 19th century were those that had experienced revivalist movements and at the same time dominated successive waves of internationalization and industrialization. In the 18th century, Christian revivalism and secular enlightenment were two independent reactions to the authoritarian excesses of the state and the church. One sought solutions in divine resources, the other in human resources; one legitimized spiritual authority by biblical revelation, the other secular authority by human reason; one shaped the attitudes requisite for worldwide Bible dissemination, the other the attitudes required for an internationalization of human relations.

The paradigm shift (1789–1830): The inflection point from low to high growth in Bible translation is due to the co-occurrence of three factors: Christian revivalism, internationalization, and industrialization. The nations that contributed most to worldwide Bible translation in the 19th century were those that had experienced revivalist movements and at the same time dominated successive waves of internationalization and industrialization. In the 18th century, Christian revivalism and secular enlightenment were two independent reactions to the authoritarian excesses of the state and the church. One sought solutions in divine resources, the other in human resources; one legitimized spiritual authority by biblical revelation, the other secular authority by human reason; one shaped the attitudes requisite for worldwide Bible dissemination, the other the attitudes required for an internationalization of human relations.

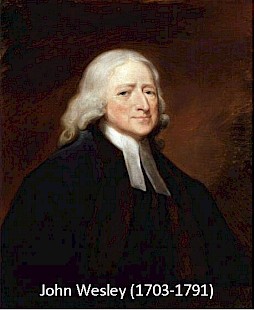

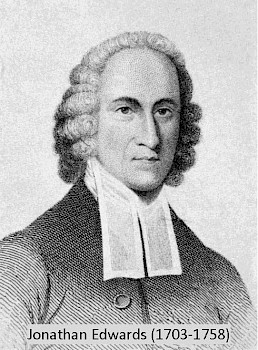

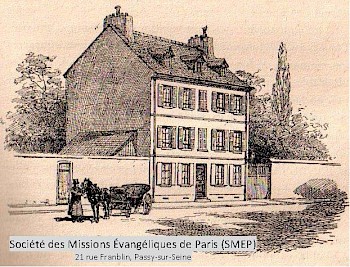

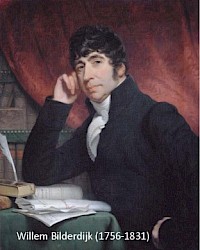

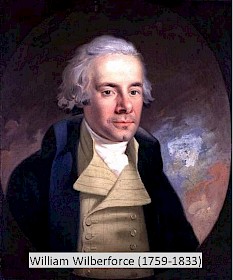

Church historians have characterized revival movements by their commitment to the Sola Scriptura principle of the Reformation and by their sense of missionBebbington (1989, pp. 2–3) calls these traits “biblicism” and “activitism”. Some religious historians in the United States have labeled this consciousness of revival movements “disinterested benevolence” and linked it to the theology of Samuel Hopkins (1721–1803) (see Elsbree, 1935; MacCormack, 1966; and Matthews, 1969). to reach out to the local community, the wider society, or distant peoples. Both this regard for the Bible and this sense of mission impel people to engage in Bible translation. In the 18th and 19th centuries, dozens of Christian revival movements swept across Europe and North America. Many were started by a prominent revival preacher and resulted in the formation of a mission or Bible society. In particular, the UK revival movements of the 18th century led to the formation of the Baptist Missionary SocietyThe Baptist Missionary Society (BMS), established in 1792 by 12 Baptist ministers in Kettering, UK, sent William Carey to India in 1793 as its first missionary. The missionary station that Carey established in Serampore organized the translation of Bible portions into more than 23 Asian languages during 1815–1914, bringing the total number of world languages with direct BMS involvement to 52 in this period (see Smith, 1885). in 1792, the London Missionary SocietyThe London Missionary Society (LMS) was founded in 1795 by a group of evangelical Anglicans and Congregationalists. Prominent LMS missionaries in the 19th and 20th centuries were Robert Morrison (China), David Livingston (Africa), and the 1924 Olympic Games gold medalist Eric Liddell (China). The LMS translated Scriptures for the first time into 26 languages. in 1795, the Church Mission SocietyThe Church Mission Society (CMS) was created in 1799 by a group of Anglican and evangelical Christians centered around William Wilberforce, a member of the British Parliament. Its original name, Society for Missions to Africa and the East, was changed to Church Mission Society in 1812. Between 1815 and 1914, the CMS supervised the translation of Bible portions into at least 52 languages (see Murray, 1985). in 1799, and the British and Foreign Bible SocietyA group that included William Wilberforce and Thomas Charles formed the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) in 1804 to supply affordable Bibles to the people. From the outset, as its name indicates, it was not intended to serve only the churches in the United Kingdom, but to extend its agency into other parts of the world. The BFBS rarely engaged in Bible translation itself: BFBS employees translated portions of the Bible into only five languages between 1815 and 1914. During this period, however, the BFBS was the sole or main publisher of Bible portions in about 184 languages. It organized the publication process in about 150 languages by using printing facilities around the world. The BFBS set up 10 auxiliary Bible societies in Australia, Canada, India, and Indonesia responsible for publishing Bible portions in an additional 34 languages. Most of these auxiliary Bible societies turned into national Bible societies. For example, the Calcutta Auxiliary Bible Society of 1811 became the Bible Society of India in 1950, and the New South Wales Auxiliary Bible Society of 1827 became the Australian Bible Society. In the first 75 years of its existence, the BFBS published Bible portions in 33 languages before accelerating its output to 151 languages between 1880 and 1914. in 1804. North America saw the establishment of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign MissionsThe American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was formed in 1810 by alumni of Williams College in Massachusetts who were part of a series of revivals in Northeast America at the beginning of the 19th century. The ABCFM, of Congregational origin, was the largest American mission agency of the 19th century. Missionaries of the ABCFM translated Scriptures into 20 languages for the first time. in 1810 and the American Bible SocietyThe American Bible Society (ABS) was founded in 1816 by several people, mainly politicians, including Elias Boudinot, Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen, Daniel Coit Gilman, and John Jay. The ABS published Bible portions in languages in which American missionaries evangelized the native population. Like the BFBS, the ABS used printing facilities all over the world for its publications. According to The Book of a Thousand Tongues, the ABS printed Bible portions or whole Bibles in 65 languages for the first time. The Encyclopedia Americana of 1918 (Vol. 1, p. 501) mentions the translation of Scriptures into 164 languages by 1915, which also includes languages in which Scriptures were already translated (see Rines, 1918). in 1816. The revival movements are difficult to quantify due to their interconnectivity and uneven spread, but together they created a sea change in the attitudes toward Bible translation as a mass movement.

Church historians have characterized revival movements by their commitment to the Sola Scriptura principle of the Reformation and by their sense of missionBebbington (1989, pp. 2–3) calls these traits “biblicism” and “activitism”. Some religious historians in the United States have labeled this consciousness of revival movements “disinterested benevolence” and linked it to the theology of Samuel Hopkins (1721–1803) (see Elsbree, 1935; MacCormack, 1966; and Matthews, 1969). to reach out to the local community, the wider society, or distant peoples. Both this regard for the Bible and this sense of mission impel people to engage in Bible translation. In the 18th and 19th centuries, dozens of Christian revival movements swept across Europe and North America. Many were started by a prominent revival preacher and resulted in the formation of a mission or Bible society. In particular, the UK revival movements of the 18th century led to the formation of the Baptist Missionary SocietyThe Baptist Missionary Society (BMS), established in 1792 by 12 Baptist ministers in Kettering, UK, sent William Carey to India in 1793 as its first missionary. The missionary station that Carey established in Serampore organized the translation of Bible portions into more than 23 Asian languages during 1815–1914, bringing the total number of world languages with direct BMS involvement to 52 in this period (see Smith, 1885). in 1792, the London Missionary SocietyThe London Missionary Society (LMS) was founded in 1795 by a group of evangelical Anglicans and Congregationalists. Prominent LMS missionaries in the 19th and 20th centuries were Robert Morrison (China), David Livingston (Africa), and the 1924 Olympic Games gold medalist Eric Liddell (China). The LMS translated Scriptures for the first time into 26 languages. in 1795, the Church Mission SocietyThe Church Mission Society (CMS) was created in 1799 by a group of Anglican and evangelical Christians centered around William Wilberforce, a member of the British Parliament. Its original name, Society for Missions to Africa and the East, was changed to Church Mission Society in 1812. Between 1815 and 1914, the CMS supervised the translation of Bible portions into at least 52 languages (see Murray, 1985). in 1799, and the British and Foreign Bible SocietyA group that included William Wilberforce and Thomas Charles formed the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) in 1804 to supply affordable Bibles to the people. From the outset, as its name indicates, it was not intended to serve only the churches in the United Kingdom, but to extend its agency into other parts of the world. The BFBS rarely engaged in Bible translation itself: BFBS employees translated portions of the Bible into only five languages between 1815 and 1914. During this period, however, the BFBS was the sole or main publisher of Bible portions in about 184 languages. It organized the publication process in about 150 languages by using printing facilities around the world. The BFBS set up 10 auxiliary Bible societies in Australia, Canada, India, and Indonesia responsible for publishing Bible portions in an additional 34 languages. Most of these auxiliary Bible societies turned into national Bible societies. For example, the Calcutta Auxiliary Bible Society of 1811 became the Bible Society of India in 1950, and the New South Wales Auxiliary Bible Society of 1827 became the Australian Bible Society. In the first 75 years of its existence, the BFBS published Bible portions in 33 languages before accelerating its output to 151 languages between 1880 and 1914. in 1804. North America saw the establishment of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign MissionsThe American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was formed in 1810 by alumni of Williams College in Massachusetts who were part of a series of revivals in Northeast America at the beginning of the 19th century. The ABCFM, of Congregational origin, was the largest American mission agency of the 19th century. Missionaries of the ABCFM translated Scriptures into 20 languages for the first time. in 1810 and the American Bible SocietyThe American Bible Society (ABS) was founded in 1816 by several people, mainly politicians, including Elias Boudinot, Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen, Daniel Coit Gilman, and John Jay. The ABS published Bible portions in languages in which American missionaries evangelized the native population. Like the BFBS, the ABS used printing facilities all over the world for its publications. According to The Book of a Thousand Tongues, the ABS printed Bible portions or whole Bibles in 65 languages for the first time. The Encyclopedia Americana of 1918 (Vol. 1, p. 501) mentions the translation of Scriptures into 164 languages by 1915, which also includes languages in which Scriptures were already translated (see Rines, 1918). in 1816. The revival movements are difficult to quantify due to their interconnectivity and uneven spread, but together they created a sea change in the attitudes toward Bible translation as a mass movement.

In the narrow time window between the French Revolution (1789) and the beginning phase of the Concert of Europe (1830), two philosophers, Jeremy Bentham and Emmanuel Kant, developed visionary ideas about international relations. For both, the space of the “international” was lawless and desperately in need of regulation.  The Englishman Bentham, who coined the term “international”, advocated a system of lawsBentham coined the term “international” in An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789). He had already outlined in 1786 a system of international laws in A plan for a Universal and Perpetual Peace (see Janis, 1984). that would bind the conduct of nations. Against the backdrop of the disorder of the French Revolution, Kant went a step further and argued in his essay Zum ewigen Frieden [Perpetual Peace] that the international space should be shaped by a law of nations backed up by a federation of free statesThese ideas are expressed in Kant’s essay of 1795 Zum ewigen Frieden. Ein philosophischer Entwurf, translated into English as To Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. The philosopher Gottfried Leibniz had already expressed his wishes for a European federation of states a century earlier (see Loemker, 1969, p. 58, footnote 9).. Bentham and Kant’s ideas inspired the architects of the Concert of Europe (1815–1878), which was mankind’s first truly international institutionKlemenz Wenzel von Metternich and his colleagues were also influenced by Lord Grenville, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during 1806–1807, who had drawn up plans for institutionalized meetings of European politicians (see Sherwig, 1962).. Its establishment by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars was a watershed in international relations. Although the Concert of Europe eventually failed, it became the reference point for continuous internationalization efforts until the present day. Mark Mazower admirably describes in his chapter Under the Sign of the InternationalSee Mazower, Marc (2012). Governing the World: The History of an Idea. New York: The Penguin Press, pp. 13–30. how the Concert of Europe appealed to the aspirations of the European public and opened an era that aroused interest in international affairs.

The Englishman Bentham, who coined the term “international”, advocated a system of lawsBentham coined the term “international” in An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789). He had already outlined in 1786 a system of international laws in A plan for a Universal and Perpetual Peace (see Janis, 1984). that would bind the conduct of nations. Against the backdrop of the disorder of the French Revolution, Kant went a step further and argued in his essay Zum ewigen Frieden [Perpetual Peace] that the international space should be shaped by a law of nations backed up by a federation of free statesThese ideas are expressed in Kant’s essay of 1795 Zum ewigen Frieden. Ein philosophischer Entwurf, translated into English as To Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. The philosopher Gottfried Leibniz had already expressed his wishes for a European federation of states a century earlier (see Loemker, 1969, p. 58, footnote 9).. Bentham and Kant’s ideas inspired the architects of the Concert of Europe (1815–1878), which was mankind’s first truly international institutionKlemenz Wenzel von Metternich and his colleagues were also influenced by Lord Grenville, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during 1806–1807, who had drawn up plans for institutionalized meetings of European politicians (see Sherwig, 1962).. Its establishment by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars was a watershed in international relations. Although the Concert of Europe eventually failed, it became the reference point for continuous internationalization efforts until the present day. Mark Mazower admirably describes in his chapter Under the Sign of the InternationalSee Mazower, Marc (2012). Governing the World: The History of an Idea. New York: The Penguin Press, pp. 13–30. how the Concert of Europe appealed to the aspirations of the European public and opened an era that aroused interest in international affairs.

The First Industrial Revolution (1780?–1840)—the transition from hand to machine production made possible by innovations in steam power and fuel techniques—primarily affected textile production and metallurgy. Innovations originated in the United Kingdom and were exported to the European continent after a short delay, first to Belgium, then to France, Germany, Scandinavia, and so forth. Although this first wave of industrialization had no direct effect on the number of Scripture translations, it laid the ground for the Second Industrial Revolution (1870–1914), which directly enabled an increase in Bible translations.

Sustained high growth (1815–1914): Between 1815 and 1914, Scriptures were translated into a total of 478 new languages, five times more languages than had been accomplished in the preceding 2000 years. The total number of languages with Scriptures grew to 572 by the year the First World War broke out.

In the 19th century, the most important structural unit for missionary outreach was the nation state not the mission agency, while in the 20th century this hierarchy was reversed. The reason for this shift lies in the gradual acquisition of international experience. For the purpose of war prevention, the Concert of Europe worked reasonably well until the Crimean War broke out in 1853 and pitted member states against one another, the Russians against the British and French. For projects like exploration, trade, and evangelization, the concept of a 19th-century–style corporation like the Concert of Europe appears insufficient. Such endeavors require a high level of mutual trust between nations, which did not exist in the 19th century. It was more effective to use the infrastructure of each nation state. European key players thus expected to gain more from pursuing colonial empires than from seeking a synergism of forces.

In the 19th century, the most important structural unit for missionary outreach was the nation state not the mission agency, while in the 20th century this hierarchy was reversed. The reason for this shift lies in the gradual acquisition of international experience. For the purpose of war prevention, the Concert of Europe worked reasonably well until the Crimean War broke out in 1853 and pitted member states against one another, the Russians against the British and French. For projects like exploration, trade, and evangelization, the concept of a 19th-century–style corporation like the Concert of Europe appears insufficient. Such endeavors require a high level of mutual trust between nations, which did not exist in the 19th century. It was more effective to use the infrastructure of each nation state. European key players thus expected to gain more from pursuing colonial empires than from seeking a synergism of forces.

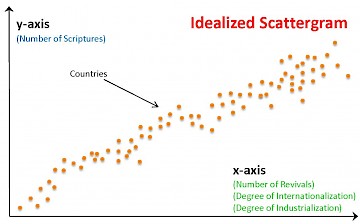

Historical data for 1815–1914 demonstrate a correlation between the number of Bible translations on the one side and the number of revival movements, the degree of internationalization, and the degree of industrialization on the other side. The more revival movements a country experienced, the higher its degree of internationalization, and the greater its level of industrialization, the more languages there were in which missionaries of that country produced Bible translations (see scattergram).

A country’s degree of internationalization can be measured by the extent of its colonial possessions, or even better by the number of languagesThe colonies varied in their potential for Bible translation. Greater-Siberia, for example, an area of 13,100,000 km2, was part of Russia since the 17th century, while Indonesia, a country of only 1,904,569 km2, was a Dutch colony until the Second World War. With a population speaking 43 languages, Siberia’s potential for Bible translation, despite its greater size, was much smaller than Indonesia’s, where 701 indigenous languages were spoken. spoken in its colonies. This number provides an upper limit of the Scripture translations the missionaries of a country could have achieved in the best of all possible worlds. A country’s level of industrialization is more difficult to quantify.  The second industrial revolution (1870–1914) was characterized by technological innovations that improved the mobility of people, information, and goods. The construction of steamships and railroad networks enabled Bible translators to travel easily to their target areas. The installation of telegraphic cable networksThe electric telegraph using Morse code gave rise to the first global communication system. The first telegraphic device, put into operation in 1844 between Washington and Baltimore, led to a surge in investments by colonial powers to forge closer links with their colonies and, not incidentally, to exert greater and more effective colonial control. The first undersea electric cable linked Britain to the European continent in 1851. Other cables connected Europe to the USA in 1866 and France to North Africa in 1871. The United Kingdom dominated the submarine cable business until the First World War. This dominance concerned other European powers as it strengthened the British grip on the commercial and financial networks (see Hanson, E. C., 2008. The information revolution and world politics. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. overland and undersea provided missionaries, among other beneficiaries, the opportunity to exchange timely information. The use of mobile steam-driven printing presses increased the circulation of translated Bibles. While these technologies enhanced the prospects for Bible translation projects, control and access to them was unevenly distributed. Countries fall into three categories:

The second industrial revolution (1870–1914) was characterized by technological innovations that improved the mobility of people, information, and goods. The construction of steamships and railroad networks enabled Bible translators to travel easily to their target areas. The installation of telegraphic cable networksThe electric telegraph using Morse code gave rise to the first global communication system. The first telegraphic device, put into operation in 1844 between Washington and Baltimore, led to a surge in investments by colonial powers to forge closer links with their colonies and, not incidentally, to exert greater and more effective colonial control. The first undersea electric cable linked Britain to the European continent in 1851. Other cables connected Europe to the USA in 1866 and France to North Africa in 1871. The United Kingdom dominated the submarine cable business until the First World War. This dominance concerned other European powers as it strengthened the British grip on the commercial and financial networks (see Hanson, E. C., 2008. The information revolution and world politics. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. overland and undersea provided missionaries, among other beneficiaries, the opportunity to exchange timely information. The use of mobile steam-driven printing presses increased the circulation of translated Bibles. While these technologies enhanced the prospects for Bible translation projects, control and access to them was unevenly distributed. Countries fall into three categories:

-

Traditional countries: countries with no or limited access to the technologies (e.g. Brazil, China, Iran);

-

Sovereign countries: countries with access to the technologies and with the ability to build transport and information networks on the territory they controlled (e.g. Western European countries, USA);

-

Hegemonic countries: sovereign countries that additionally dominated the networks built between nations and empires (i.e. United Kingdom).

Table 4 presents a list of the countries that contributed to the translation of Scriptures between 1815 and 1914. The queen in this league is the United Kingdom: it experienced the highest number of revival movements, it had access through its colonial empire to the highest number of languages, it was the hegemon of the international communication networks, and, in keeping with the pattern of the historical data, it was also far and away the most productive country in terms of Bible translation.

Worldwide Bible translation in the 19th century is thus strongly dominated by Anglo-Saxon countries with 67% of all new translations, roughly 315 of 472, produced by translators of these countries.

Explosive growth (1915–today): The number of languages into which Scriptures have been translated quintupled in the last hundred years, numbering 2850 in 2013, compared with 572 in 1914. Bible portions or whole Bibles were completed in 2278 languages between 1915 and 2013, a phenomenal acceleration. The Anglo-Saxon supremacy has become even more overwhelming with 83% of all new language translations, approximately 1901 of 2278, accomplished by Anglo-Saxon agencies.

Explosive growth (1915–today): The number of languages into which Scriptures have been translated quintupled in the last hundred years, numbering 2850 in 2013, compared with 572 in 1914. Bible portions or whole Bibles were completed in 2278 languages between 1915 and 2013, a phenomenal acceleration. The Anglo-Saxon supremacy has become even more overwhelming with 83% of all new language translations, approximately 1901 of 2278, accomplished by Anglo-Saxon agencies.

The dynamics of these increases differ from those of the 19th century. Christian revival movements no longer constitute a measurable force for two reasons. Firstly, while the 20th century saw two major revival movements—the Pentecostal and Charismatic movementsThe Azusa Street Revival of 1906 in Los Angeles is considered the start of the first Pentecostal Movement (1906–1960). It led to the formation of a worldwide network of Assemblies of God, the first of which was established in the USA in 1914. The second Pentecostal Movement (after 1960), often referred to as the Charismatic Movement, is a revival movement within the established Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox denominations. It did not result in the establishment of an independent denomination (see Menzies and Menzies, 2000). that led to the formation of missions such as the Assembly of God Mission—these movements contributed only a small share of the total Scripture output, about 14This number refers to the number of translations accomplished by members of the Assemblies of God Missions (AGM). The number of translations contributed by members of the Pentecostal and Charismatic movements as a whole might be significantly higher than 14 due to the fact that Charismatic missionaries often enrolled with interdenominational mission agencies that specialized in Bible translation (e.g. Wycliffe Bible Translators). Precise statistics are not available or derivable. out of 2278 new translations. Second, due to global migration and information technology some conversion movements among unevangelized populations fed backIn the 20th century, African immigrants established fervent Christian churches in European and North-American cities which interacted with local Western churches. to Western countries. The boundary between cause (revival in base country) and effect (conversion in target country) thus became blurred. For these reasons, variation in revival movements cannot be used to explain variation in the number of translated Bibles.

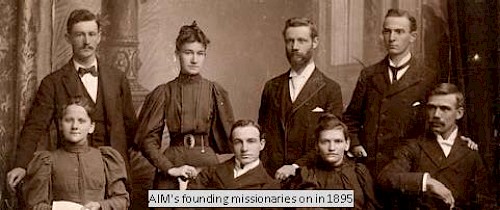

The spread of information technology is one important factor that has contributed to the rapid growth of Scriptures. Three types of technological innovations particularly fostered translation projects by industrializing parts of the procedure and reducing the time required to produce a translation: personal computer technologiesApple II computers began mass production in 1977, launching the personal computer industry. IBM entered and quickly dominated the market with MS-DOS after 1981. Word processing and database software were among the first applications running on personal computers. Because every Bible translation project requires a dictionary and a writing system, if these are not available the translator must create them, which is a time-consuming task. PC technologies dramatically reduced the time needed for production of these tools. In 1989, for example, the Summer Institute of Linguistics introduced a dictionary software called Shoebox, the name of which alludes to the traditional way field linguists stored lexical data on cards. In 2003, the United Bible Societies and the Summer Institute of Linguistics jointly developed the translator software Paratext, which packages in one display a selection of Bible versions and exegetical help. (e.g. word processing, database management); encoding technologies for writing systemsISO 8859 and the improved Unicode are industrial standards for encoding the characters of writing systems. Unicode, for example, contains codes for 120,000 characters covering 129 modern and historic writing systems. Unicode is used in most operating systems and allows characters to be available in ordinary word processors. (e.g. based on ISO 8859 or Unicode); and internet and mobile technologiesDuring 1980–2013, internet and mobile technologies developed in a series of cascading innovations (Hanson, 2008, pp. 48–69): The first satellite was launched into a geosynchronous orbit in 1963; ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network), the first computer network which was operated by the US Department of Defense, began service in 1969; the first fiber-optic cable across the Atlantic Ocean went into service in 1988; the Word Wide Web was invented by Tim Berners-Lee (CERN) in Switzerland in 1989; handheld mobile telephones were first developed in the early 1990s. These technologies transformed the process of Bible translation. Revisions of a Bible text, for example, can be easily exchanged, video-conferencing can bring together a translation committee scattered over three continents, and so forth. (e.g. traffic of texts, data, audio, and video). These technologies have had a measurable effect on the time needed to complete a given translation project. New Testament projects begun after 1980 took half as long as those initiated before 1980. For complete Bible projects, the time savings is even more dramatic: one third of the time needed before 1980 is required for the same task after 1980.