Introduction

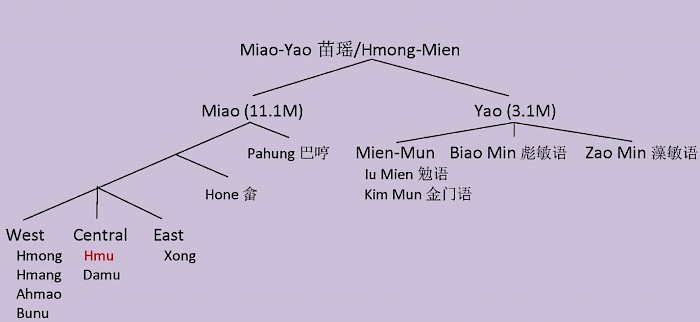

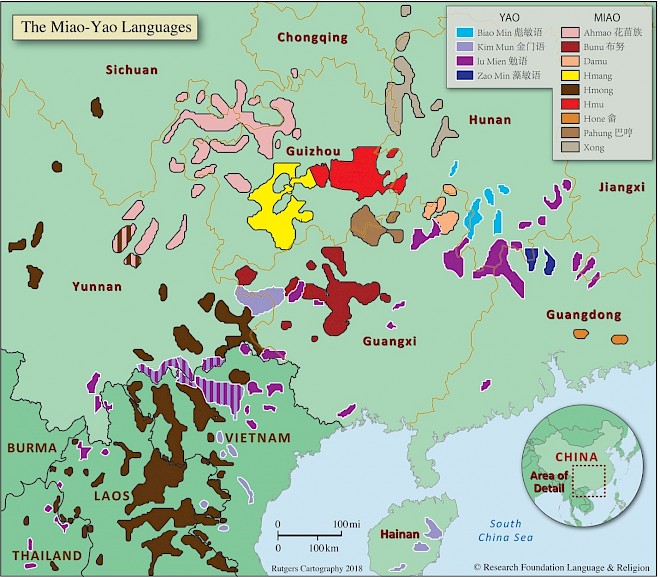

The Miao-Yao 苗瑶 or Hmong-Mien languages are spoken by 14.2 million people primarily in Southwest China as well as the northern parts of Vietnam, Laos and Thailand. The Miao-Yao people are less populous and migrated less extensively than the Tai-Kadai groups. In the below sections, we describe a phylogenetic project and document linguistic highlights of the Miao languages.

Phylogenetics

The Miao-Yao (Hmong-Mien) languages are spoken in nine provinces of Southwest China and across the border in neighboring Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand.

Purnell’s reconstructionSee Purnell, H., 1970, Toward a reconstruction of Proto-Miao-Yao. PhD dissertation. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University. of Proto Miao-Yao premised on 20 contemporary languages signified the first milestone on the path of establishing the Miao-Yao family. In light of the scarcity of data available from China where more than 90% of the Miao-Yao population dwells, this work is now considered to be outdated.

Purnell’s reconstructionSee Purnell, H., 1970, Toward a reconstruction of Proto-Miao-Yao. PhD dissertation. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University. of Proto Miao-Yao premised on 20 contemporary languages signified the first milestone on the path of establishing the Miao-Yao family. In light of the scarcity of data available from China where more than 90% of the Miao-Yao population dwells, this work is now considered to be outdated.

Chinese scholarsSee Wáng Fǔshì 王辅世, 1979, The comparison of initials and finals of Miao dialects 苗语方言声母韵母比较. Monograph presented at the 12th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, October 19-21, Paris.

Wáng Fǔshì 王辅世, 1994, Reconstruction of the sound system of Proto-Miao 苗语古音构拟. Tokyo: Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa.

Wáng Fǔshì 王辅世 and Máo Zōngwǔ 毛宗武, 1995, Reconstruction of the sound system of Proto-Miao 苗语古音构拟. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press 中国社会科学出版社., in particular Wáng Fǔshì, published broad data from Miao-Yao languages within China several years later. Wáng and his colleagues established a tri-partite division of the Miao languages (Western, Central and Eastern) and then established a linkage between Miao-Yao languages to the Sino-Tibetan family. However, this connection was rejected by most Western scholars due to the large number of Chinese loanwords in the reconstructions. Their raw data, nevertheless, formed the basis of further reconstructionsSee Niederer, B., 1998, Les langues Hmong-Mjen (Miáo-Yáo): Phonologie historique. Lincom Studies in Asian Linguistics 7. Munich: Lincom Europa.

Consider especially:

Ratliff, M., 2010, Hmong-Mien Language History. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. of Miao-Yao languages.

Native legends of the Miao people point toward an ancient migration from a “cold land in the northSee Savina, F. M., 1924, Histoire des Miao. Paris: Société des Missions Etrangères.”; some myths mention an ancient indigenous script that the ancestors of the Miao lost in the process of forced migration. Remnants of this pictographic writing are said to be preserved in the sophisticated embroidery patternSee Enwall, J. (1994). A myth become reality. History and development of the Miao written language. Volume 1 and 2. Stockholm: University of Stockholm. of clothes and costumes. However, as per Han Chinese records, “Miao 苗” is the name used for non-Chinese groups living in the Yangtze basin south of the Han areas during the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC). Most scholars therefore see no linguistic evidenceOn this point, see especially Sagart, L., 1995, Chinese ‘buy’ and ‘sell’ and the direction of borrowings between Chinese and Hmong-Mian: A response to Haudricourt and Strecker. T'oung Pao 81(4-5), 328-344 (on p. 341). for a place of origin of the Miao-Yao people other than China. After the 18th century AD, some Miao and Yao groups moved out of China into neighboring countries: Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar. In the aftermath of the Second Indochina War (1960-1975), about 100,000 ethnic Miao and Yao were compelled to become refugees in the United States, France and Australia because they were allied with anti-communist forces that had lost the war. These Miao groups generally use Hmong as their selfname, similar to all Western Miao. While most scholars have not developed migration theories, they do concede that the Miao people dwelling outside of China descend from the Western Miao subgroup.

Native legends of the Miao people point toward an ancient migration from a “cold land in the northSee Savina, F. M., 1924, Histoire des Miao. Paris: Société des Missions Etrangères.”; some myths mention an ancient indigenous script that the ancestors of the Miao lost in the process of forced migration. Remnants of this pictographic writing are said to be preserved in the sophisticated embroidery patternSee Enwall, J. (1994). A myth become reality. History and development of the Miao written language. Volume 1 and 2. Stockholm: University of Stockholm. of clothes and costumes. However, as per Han Chinese records, “Miao 苗” is the name used for non-Chinese groups living in the Yangtze basin south of the Han areas during the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC). Most scholars therefore see no linguistic evidenceOn this point, see especially Sagart, L., 1995, Chinese ‘buy’ and ‘sell’ and the direction of borrowings between Chinese and Hmong-Mian: A response to Haudricourt and Strecker. T'oung Pao 81(4-5), 328-344 (on p. 341). for a place of origin of the Miao-Yao people other than China. After the 18th century AD, some Miao and Yao groups moved out of China into neighboring countries: Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar. In the aftermath of the Second Indochina War (1960-1975), about 100,000 ethnic Miao and Yao were compelled to become refugees in the United States, France and Australia because they were allied with anti-communist forces that had lost the war. These Miao groups generally use Hmong as their selfname, similar to all Western Miao. While most scholars have not developed migration theories, they do concede that the Miao people dwelling outside of China descend from the Western Miao subgroup.

Another group that might have been incited to migrate out of China is the Hmu, or Central Miao. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Hmu mounted three rebellions in against the imperial government Guìzhōu Province, all of which resulted in defeat:

-

the First Miao Rebellion (1735-1738),

-

the Second Miao Rebellion (1795-1806) and

-

the Third Miao Rebellion (1854-1873).

Robert JenksSee Jenks, R., 1994, Insurgency and social disorder in Guìzhōu. The “Miao” Rebellion 1854-1873. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. relates the motivations for the Miao to revolt to three types of grievances: the alienation of ancestral land by Han merchants, excessive government taxation, and maladministration on the part of officials. In addition to the Miao, other ethnic minorities, Muslims, discontented Han, and religious folk sects joined the insurrections during which, according to one account, almost five million people lost their lives and vast areas were depopulated. Besides anecdotal evidence, little to no data is available about population moving out of Southeast Guìzhōu, the epicenter of the conflict. If such moves did occur, it is highly likely that the Miao walked through Guangxi province. Two questions need to be answered in order to help (dis)prove the issue of Central Miao’s migration into Southeast Asia in the 19th century or earlier:

-

Did Proto-Western Miao, Proto-Central Miao, and Proto-Eastern Miao separate from each other at the same time or do two of them share a closer relationship?

-

Is the Bunu language of 400,000 speakers a Western Miao language, a Central Miao language, or an independent Miao language? The Bunu people, living in Central Guangxi province, were included by the Central Government in the Yao nationality, although they speak a Miao languageSee Strecker, D., 1987, Some Elements on Benedict’s “Miao-Yao enigma: The Na’e language.” Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 10(2), 22-42.. The genetic position of the Bunu language may illuminate key information on Miao migration patterns.

Documentation

In this section, we survey the Miao group in the domains of phonology, morphology, syntax, tense, aspect, and mood.

The Miao languages exhibit similar phonological systems with (C)(C)V(V)(C)T constituting the basic syllable structure. Several Miao languages use nasalized vowels and either six or eight tones.

We sketch three peculiar consonant subsets, the Hmu three-way set of fricative consonants, the 27 simple plosive consonants in Xong and the stop-lateral clusters in Western Miao languages.

The HmuHmu is a central Miao language spoken in Southeast Guìzhōu by about 1.4 million people. The data presented in this were collected by Matthias Gerner during 1996-2003. language exhibits a notable three-way contrast in fricative consonants (voiced/unvoiced/aspirated), whereas plosive consonants only distinguish two modes of articulation (unvoiced/aspirated).

|

[p]: |

pɛ35 |

‘full’ |

[t]: |

tən31 |

‘step on’ |

|

|

|

[k]: |

ki35 |

‘lift’ |

[q]: |

qei53 |

‘bald’ |

|

[pʰ]: |

pʰɛ33 |

‘repair’ |

[tʰ]: |

|

|

|

|

|

[kʰ]: |

kʰi33 |

|

[qʰ]: |

qʰei33 |

‘tie’ |

|

[v]: |

vɛ31 |

‘change’ |

[zIn Chinese loanwords such as rén 人.]: |

zən31 |

‘person’ |

[ʑ]: |

ʑa31 |

‘eight’ |

[ɣ]: |

ɣi33 |

‘stone’ |

|

|

|

|

[f]: |

fa11 |

‘rise’ |

[s]: |

sən33 |

‘cold’ |

[ɕ]: |

ɕa35 |

‘difficult’ |

|

|

|

[χ]: |

χei33 |

‘stick’ |

|

[fʰ]: |

fʰɛ35 |

‘turn over’ |

[sʰ]: |

sʰən44 |

‘believe’ |

[ɕʰ]: |

ɕʰa35 |

‘spend’ |

[xʰ]: |

xʰi44 |

‘quick’ |

|

|

|

Table 1: Plosive and fricative consonants in Hmu

In XongXong is an Eastern Miao language spoken by 900,000 people in Húnán 湖南 province. The data in this section are quoted from Sposato’s Grammar of Xong (2015) which analyzes the Xong language of Fènghuáng 凤凰county.

Sposato, A. M., 2015, A grammar of Xong. PhD Dissertation. New York: State University of New York at Buffalo., plosive consonants allow an exceptional number of secondary articulations such as prenasalization, palatalization, aspiration, and double or triple combinations thereof. These secondary articulations collectively build up a system of 27 simple stops for four points of articulation (bilabial, alveolar, velar, uvular).

|

[p]: |

pã41 |

‘half’ |

[t]: |

taw14 |

‘speech’ |

|

|

|

[k]: |

ki14 |

‘wind’ |

[q]: |

qɤ43 |

‘village’ |

|

[mp]: |

mpã454 |

‘think’ |

[nt]: |

ntaw14 |

‘tree’ |

[ŋk]: |

ŋka41 |

‘medicine’ |

[Nq]: |

Nqɤ41 |

‘sing’ |

|||

|

[pj]: |

pjɛɰ43 |

‘home’ |

[tj]: |

tju43 |

‘complete’ |

|

|

|

[kj]: |

kja41 |

‘stir-fry’ |

|

|

|

|

[ph]: |

phu22 |

‘speak’ |

[th]: |

thi21 |

‘stomach’ |

|

|

|

[kh]: |

kho43 |

‘poor’ |

[qh]: |

qha43 |

‘dry’ |

|

|

|

|

[ntj]: |

ntju22 |

‘to peck’ |

|

|

|

[ŋkj]: |

ŋkjɛ41 |

‘gold’ |

|

|

|

|

[mph]: |

mphã43 |

‘ant’ |

[nth]: |

ntha43 |

‘take off’ |

|

|

|

[ŋkh]: |

ŋkha43 |

‘bow’ |

[Nqh]: |

Nqhɛɰ43 |

‘fall out’ |

|

[pjh]: |

pjha21 |

‘blow’ |

[tjh]: |

tjhu14 |

‘press down’ |

|

|

|

[kjh]: |

kjha22 |

‘open’ |

|

|

|

|

[mpjh]: |

mpjha21 |

‘measure’ |

[ntjh]: |

ntjho14 |

‘smoky’ |

|

|

|

[ŋkjh]: |

ŋkjho41 |

‘magic’ |

|

|

|

Table 2: Secondary articulations in Xong

A distinct trait of Western Miao languages is the inclusion of plosive-lateral clusters. It is notable that these complex consonants are not attested in Central and Eastern Miao languages. Plosive-lateral clusters exist in Hékǒu HmongThis Western Hmong language is spoken in Hékǒu 河口 county of Yúnnán province. The data of Table 3 are quoted from:

Xióng Yùyǒu 熊玉有 and Diana Cohen 戴虹恩, 2005, Student’s practical Miao-Chinese-English Handbook 苗汉英学习实用手册. Kunming: Yúnnán Nationalities Press 云南民族出版社. for the bilabial and alveolar points of articulation, while in Green HmongGreen Hmong or Blue Hmong (the Hmong color term njua means green or blue) is a Western Miao language spoken in the provinces of Phrae and Nan in northern Thailand. The data are quoted from Lyman’s Grammar of Mong Njua:

Lyman, T. A., 1979, Grammar of Mong Njua (Green Miao). Sattley, California: The Blue Oak Press. they are formed for the bilabial and velar positions.

|

[pl]: |

pla33 |

‘once’ |

[tl]: |

tla35 |

‘spoon’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[phl]: |

phlo44 |

‘cheeks’ |

[thl]: |

thla44 |

‘run’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[mpl]: |

mpla33 |

‘slippery’ |

[ntl]: |

ntla35 |

‘ask’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[mphl]: |

mphlai54 |

‘ring’ |

[nthl]: |

nthlao33 |

‘hoop’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3: Plosive-Lateral Clusters in Hékǒu Hmong

|

[pl]: |

pláu |

‘four’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[kl]: |

kláw |

‘white’ |

|

|

|

|

[phl]: |

phlaw |

‘shock’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[khl]: |

khlěŋ |

Particle |

|

|

|

|

[mpl]: |

mplê |

‘paddy’ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[ŋkl]: |

ŋklua |

‘flash’ |

|

|

|

|

[mphl]: |

(no illustration) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

[ŋkhl]: |

(no illustration) |

|

|

|

||

Table 4: Plosive-Lateral Clusters in Green Hmong

Several Miao languages incorporate the use of nasalized vowels. The vowel system in XongXong is an Eastern Miao language spoken by 900,000 people in Húnán province. The data are quoted from Sposato (2015:82-92).

Sposato, A. M., 2015, A grammar of Xong. PhD Dissertation. New York: State University of New York at Buffalo., for example, involves four nasalized monophtongs along with one nasalized diphthong.

|

Vowel type |

|

unrounded |

rounded |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

front |

central |

back |

back |

|

Monophthongs |

high |

i, ĩ |

|

|

u |

|

|

mid |

|

|

ɤ |

o, õ |

|

|

low |

ɛ |

a, ã |

ɑ, ɑ̃ |

ɔ, ɔː |

|

Diphthongs |

|

ɛɰ |

au |

ɤi, ɤ̃i |

|

Table 5: The Xong (nasalized) vowel system

|

Vowel Contrast |

Examples |

|

|---|---|---|

|

i – ĩ |

mi454 ‘meter classifier’ |

mĩ454 ‘understand’ |

|

a – ã |

npa14 ‘pig’ |

npã454 ‘think’ |

|

ɑ – ɑ̃ |

mɑ43 ‘blister, boil’ |

mɑ̃43 ‘insect’ |

|

o – õ |

ŋo454 ‘fierce’ |

ŋõ454 ‘silver’ |

|

ɤi – ɤ̃i |

mɤi43 ‘coal’ |

mɤ̃i43 ‘human classifier’ |

Table 6: Plain and Nasalized Vowels in Xong

Two types of tone systems are attested. Hmong, Ahmao, and Xong exhibit six tones, of which, two further intersect with the phonation type of breathy voicing. In Hmong, the tones [21] and [33] contrast regularly breathy voicing versus non-breathy unvoicing. In Ahmao, it is the tones [21] and [33] whereas in Xong, it is the tones [22] versus [43]. The Hmu language does not use breathy voicing and has developed eight tones.

|

HmongHékǒu Hmong is a Western Miao language spoken in Hékǒu 河口 county of Yúnnán province, see Xiong and Cohen (2005: 12). Xióng Yùyǒu 熊玉有 and Diana Cohen 戴虹恩, 2005, Student’s practical Miao-Chinese-English Handbook 苗汉英学习实用手册. Kunming: Yúnnán Nationalities Press 云南民族出版社. |

6 tones |

[54] |

[42] |

[35] |

[44] |

[21] |

[33] |

|

|

|

(China) |

|

po54 ‘feed’ |

po42 ‘woman’ |

po35 ‘full’ |

po44 ‘width’ |

po21 ‘see’The non-breathy unvoiced phonation type contrasts with the breathy voiced phonation type: po21 ‘see’ versus po̤21 ‘thorn’. | po33 ‘conceal’The non-breathy unvoiced phonation type contrasts with the breathy voiced phonation type: po33 ‘conceal’ versus po̤33 ‘grandmother’. |

|

|

|

|

|

tua54 ‘thick’ |

tua42 ‘come’ |

tua35 ‘husk’ |

tua44 ‘kill’ |

tua21 ‘step on’ |

tua33 ‘die’ |

|

|

|

HmuHmu is a central Miao language spoken in Southeast Guìzhōu by about 1.4 million people. The examples in this table are quoted from Zhāng Yǒngxiáng 张永祥 and Xǔ Shìrén 许士仁, 1990, Miao-Han Dictionary 苗汉词典. Guiyang: Guìzhōu Nationalities Press 贵州民族出版社. |

8 tones |

[55] |

[31] |

[35] |

[44] |

[11] |

[33] |

[13] |

[53] |

|

(China) |

|

ta55 ‘come’ |

ta31 ‘throw’ |

ta35 ‘long’ |

ta44 ‘roast’ |

ta11 ‘lose’ |

ta33 ‘earth’ |

ta13 ‘die’ |

ta53 ‘wing’ |

|

|

|

ki55 ‘mus. Instr.’ |

ki31 ‘ditch’ |

ki35 ‘kind’ |

ki44 ‘egg’ |

ki11 ‘dry’ |

ki33 ‘corner’ |

ki13 ‘reveal’ |

ki53 ‘a bit’ |

The Miao languages contain systems of classifiers and demonstratives that are unusual from a cross-linguistic perspective. More specifically, the classifier declinations of Ahmao inflecting each classifier in six forms are unparalleled. Hmu encodes the contrast of specific versus unspecific reference in a minimal pair of forms, more specifically bare classifiers versus unspecific bare nouns. Furthermore, all Miao languages use one demonstrative reserved for marking the recognitial feature. Ahmao employs four demonstratives marking altitude, while Hmong uses three positional demonstratives, thereby indicating the position of an object relative to the speaker.

AhmaoThe earliest report of the Ahmao classifier system came from Wáng Fǔshì (1957) and the native Ahmao scholar Wáng Déguāng (1987). The data quoted in this section represent data originating from discussions between Wáng Déguāng and Matthias Gerner in 2005 shortly before the Ahmao teacher passed away. These data were then analyzed and published in Gerner and Bisang (2008, 2009, 2010).

Wáng Fǔshì 王辅世, 1957, The classifier in the Wēiníng dialect of the Miao language 贵州威宁苗语量词. Yǔyán Yánjiū 语言研究, 75-121.

Wáng Déguāng 王德光, 1987, Additional remarks on the classifiers of the Miao language in Wēiníng county. 贵州威宁苗语量词拾遗. Mínzú Yǔwén 民族语文 5: 36-39.

Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2008, Inflectional Speaker-Role Classifiers in Wēiníng Ahmao. Journal of Pragmatics 40(4), 719-732.

Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2009, Inflectional classifiers in Wēiníng Ahmao: Mirror of the history of a people. Folia Linguistica Historica 30(1/2), 183-218. Societas Linguistica Europaea.

Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2010, Classifier declinations in an isolating language: On a rarity in Wēiníng Ahmao. Language and Linguistics 11(3), 576-623. Taibei: Academia Sinica., a Western Miao language spoken in Wēiníng county of Guìzhōu province, inflects each of its ca. 50 classifiers in six forms and contrasts with other isolating languages (including other Miao languages), wherein nominal classifiers are unique indeclinable morphemes. Each classifier encodes a threefold meaning: a size value (the classified is augmentative, medial, diminutive), a definiteness value (the classified is definite, indefinite), as well as a register value (the speaker is male, female, and child). The size parameter is seen to correlate with the gender and age of the speaker in the following manner. Men typically employ augmentative classifiers, whereas women use medial classifiers. Meanwhile, children make use of diminutive classifiers.

(A) Form

If CVT indicates the base form (and augmentative, definite, male being its base values), the classifier paradigm can be represented in the following mannerC in the following table means “consonant” (simple, double, affricated, etc.); V means “vowel” (simple, double); T means “tone”, using numbers 1-5 to indicate pitch contours; * after a consonant means “suprasegmental phenomenon” (e.g. aspiration), but possibly absence of sound change as well..

|

Speaker’s Gender / Age |

Size |

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Male |

Augmentative |

CVT |

C*VT |

|

Female |

Medial |

Cai55 |

C*ai213 |

|

Children |

Diminutive |

Ca53 |

C*a35 |

Table 7: Inflectional paradigm of Ahmao Classifiers

It is possible to distinguish individual paradigms by understanding the manner in which indefinite forms are derived from their definite counterparts, for example, by voicing the initial consonant of the base form, by aspirating it, or by altering the tone.

(1) Indefinites are formed by voicing. A prominent exponent of this sound change is the plural and mass quantifier ti55 that uses a voiceless stop for the definite and voiced stop [d] for the indefinite forms. The augmentative definite and augmentative indefinite forms are further differentiated by a change in tone [55] to [31], see Table 8. Another example is the wide-spread animate classifier tu44 with cognates in the majority of other Miao languages. This classifier also functions as classifier of tools in Ahmao, see Table 9. The classifier for weather droppings ŋkey53 ‘shower’ voices the complex nasal-stop consonant in order to form the indefinite classifiers, see Table 10.

|

Speaker’s Gender/Age |

Size |

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Male |

Augmentative |

ti55 |

di31 |

|

Female |

Medial |

tiai55 |

diai213 |

|

Children |

Diminutive |

tia55 |

dia55 |

Table 8: Plural and Mass Classifier

|

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|

|

tu44 |

du31 |

|

tai44 |

dai213 |

|

ta44 |

da35 |

Table 9: Animate Classifier

|

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|

|

ŋkey53 |

ŋgey31 |

|

ŋkai53 |

ŋgai213 |

|

ŋkya53 |

ŋgeya35 |

Table 10: Classifier for Weather Droppings

(2) Indefinites are formed by (de)aspiration. The Ahmao classifier dʑa53 for lengthy objects (mainly for streets) uses voiced aspiration of the initial consonant in order to derive the indefinite classifiers from the definite classifiers, see Table 11. The voiced aspiration process occurs only on the augmentative forms for the classifiers bey53 ‘heap’ and gau53 ‘block, group’, whereas the medial and diminutive forms remain unaspirated. Meanwhile the [u] vowel is preserved for the indefinite forms of gau53, see Tables 12 and 13.

|

Speaker’s Gender/Age |

Size |

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Male |

Augmentative |

dʑa53 |

dʑɦa11 |

|

Female |

Medial |

dʑai53 |

dʑɦai213 |

|

Children |

Diminutive |

dʑa53 |

dʑɦa35 |

Table 11: Classifier for streets

|

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|

|

bey53 |

bɦey11 |

|

bai53 |

bai213 |

|

ba53 |

ba35 |

Table 12: Classifier ‘heap’

|

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|

|

gau53 |

gɦau11 |

|

gai53 |

guai213 |

|

ga53 |

gua35 |

Table 13: Classifier ‘block’, ‘group’

Interestingly, an inverted process of de-aspiration is also attested in a number of examples. The classifier of granules (e.g. sugar, rice) dlɦi35 de-aspirates the initial consonant below.

|

Speaker’s Gender/Age |

Size |

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Male |

Augmentative |

dlɦi35 |

dli44 |

|

Female |

Medial |

dlɦai213 |

dliai213 |

|

Children |

Diminutive |

dlɦa35 |

dlia35 |

Table 14: Classifier for granules

(3) Indefinites are formed by tone changes . Another group of classifiers relies on tone changes to differentiate between definite and indefinite classifiers. These tone derivations are stable for the medial-indefinite [213] and the diminutive-indefinite forms [35]. The tones of the augmentative-indefinite form are unstable. The ubiquitous inanimate classifier lu55 with cognates in other Miao languages derives the indefinite classifier by a change in tone [55] → [33], see Table 15. A small number of classifiers with tone changes for augmentative forms add other phonation processes, such as labialization or palatalization, on medial and diminutive forms. The two paradigms of Table 16 and 17 illustrate labialization and palatalization. However, the second process, namely, palatalization, has not yet fully developed.

|

Speaker’s Gender/Age |

Size |

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Male |

Augmentative |

lu55 |

lu33 |

|

Female |

Medial |

lai55 |

lai213 |

|

Children |

Diminutive |

la53 |

la35 |

Table 15: Inanimate Classifier

|

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|

|

zo53 |

zo31 |

|

zuai55 |

zuai53 |

|

zua53 |

zua35 |

Table 16: Classifier ‘bridge’

|

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|

|

ʂey55 |

ʂey44 |

|

ʂ(e)yai55 |

ʂ(e)yai213 |

|

ʂ(e)ya55 |

ʂ(e)ya35 |

Table 17: Classifier ‘liter’

(4) Indefinites are formed by other changes. Some classifiers exhibit atypical medial forms, albeit to a lesser extent atypical diminutive forms as well. One of these, the classifier tey11 ‘clump’, is depicted below. The augmentative form does not distinguish between the meanings of definite and indefinite.

|

Speaker’s Gender/Age |

Size |

Definite |

Indefinite |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Male |

Augmentative |

tey11 |

tey11 |

|

Female |

Medial |

tui11 |

tui213 |

|

Children |

Diminutive |

tya11 |

tya35 |

Table 18: Classifier ‘clump’

(B) Meaning and use

Each Ahmao classifier qualifies the size of the noun referent (augmentative, medial, diminutive), specifies its discourse prominence (definite, indefinite) and belongs to a social register (male, female, child). In direct discourse, men typically choose a male register classifier, sometimes a female register classifier, and rarely a child register classifier. If they use a classifier of another register, they want to illuminate an inner mood or implicate some hidden meanings. Women typically employ female classifiers and sometimes a male register classifier in order to be provocative. Children generally utilize a classifier of their register but occasionally use a female classifier as well, though rarely a male classifier.

| Ahmao (Wēiníng County) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) |

a. |

lu55 |

ŋgɦa35 |

ȵi55 |

zau44 |

ta55die31 |

ma11? |

|

|

|

|

CL.AUG.DEF |

house |

DEM.PROX |

good |

very |

SOL |

|

|

Male speaker: ‘The big house is very nice, isn’t it?’ [Neutral] Female speaker: ‘The big house is very nice, isn’t it?’ [Audacious or boyish] Child speaker: ‘The big house is very nice, isn’t it?’ [Odd] |

||||||||

|

|

b. |

lai55 |

ŋgɦa35 |

ȵi55 |

zau44 |

ta55die31 |

ma11? |

|

|

|

|

CL.MED.DEF |

house |

DEM.PROX |

good |

very |

SOL |

|

|

Male speaker: ‘The house is very nice, isn’t it?’ [Modest] Female speaker: ‘The house is very nice, isn’t it?’ [Neutral] Child speaker: ‘The (big) house is very nice, isn’t it?’ [Neutral] |

||||||||

|

|

c. |

la53 |

ŋgɦa35 |

ȵi55 |

zau44 |

ta55die31 |

ma11? |

|

|

|

|

CL.DIM.DEF |

house |

DEM.PROX |

good |

very |

SOL |

|

|

Male speaker: ‘The small house is very nice, isn’t it?’ [Imitating children] Female speaker: ‘The small house is very nice, isn’t it?’ [Neutral] Child speaker: ‘The (small) house is very nice, isn’t it?’ [Neutral] |

||||||||

The same size-related meanings and pragmatic nuances also hold for the subset of indefinite classifier forms. In the following three examples presented below, indefinite classifiers of animacy occur in a transitive existential construction.

|

(2) |

a. |

ȵɦi11 |

mɦa35 |

du31 |

zau44 |

ȵɦu35. |

||

|

|

|

3.SG |

have |

CL.AUG.INDEF |

good |

ox. |

||

|

Male speaker: ‘He has a nice big ox.’ [Neutral] Female speaker: ‘He has a nice big ox.’ [Audacious or boyish] Child speaker: ‘He has a nice big ox.’ [Odd] |

||||||||

|

|

b. |

ȵɦi11 |

mɦa35 |

dai213 |

zau44 |

ȵɦu35. |

||

|

|

|

3.SG |

have |

CL.MED.INDEF |

good |

ox. |

||

|

Male speaker: ‘He has a nice big ox.’ [Modest] Female speaker: ‘He has a nice big ox.’ [Neutral] Child speaker: ‘He has a nice (big) ox.’ [Neutral] |

||||||||

|

|

c. |

ȵɦi11 |

mɦa35 |

da35 |

zau44 |

ȵɦu35. |

||

|

|

|

3.SG |

have |

CL.DIM.INDEF |

good |

ox. |

||

|

Male speaker: ‘He has a nice big ox.’ [Imitating children] Female speaker: ‘He has a nice big ox.’ [Neutral] Child speaker: ‘He has a nice (little) ox.’ [Neutral] |

||||||||

(C) Grammatizalization of classifiers

Special forces of change have brought this system to the fore. The single-morpheme classifiers were initially divided into three size classifiers. At a later stage, they were further split into three definite and three indefinite classifiers.

(1) Size split. Ahmao synchronically involves two nominal prefixes, an augmentative, and a diminutive prefix. The augmentative prefix is related to the term ‘mother’, and the diminutive prefix to the term ‘child’.

|

Lexical Origin |

Derived Prefix |

|---|---|

|

ɲie53 ‘mother’ |

a55ɲie53 (Augmentative) |

|

ŋa55ʑau11 ‘child’ |

ŋa11 (Diminutive) |

Table 19: Origin of Size Prefixes in Ahmao

In Ahmao, the augmentative string a55ɲie53 can be prefixed to animal nouns, thereby indicating the female gender of animals (though not used for people). Furthermore, it may be prefixed to inanimate nouns in order to infer a sense of largeness, either physically or metaphorically. The diminutive prefix ŋa11 combines with the same range of nouns as a55ɲie53 and denotes the young animal of adult-young animal pairs. Moreover, with inanimate nouns, it refers to a diminutive version of the noun. Both prefixes have been contrasted in the following chart.

|

Noun |

Augmentative prefix a55ɲie53 |

Diminutive prefix ŋa11 |

|---|---|---|

|

ȵɦu35 ‘ox, bull’ |

a55ɲie53ȵɦu35 ‘cow’ |

ŋa11ȵɦu35 ‘calf’ |

|

nɦɯ11 ‘horse, stallion’ |

a55ɲie53nɦɯ11 ‘mare’ |

ŋa11nɦɯ11 ‘colt, foal’ |

|

ʑɦaɯ35 ‘sheep, ram’ |

a55ɲie53ʑɦaɯ35 ‘ewe’ |

ŋa11ʑɦaɯ35 ‘lamb’ |

|

mpa44 ‘pig, hog, boar’ |

a55ɲie53mpa44 ‘sow’ |

ŋa11mpa44 ‘piglet’ |

|

tli55 ‘dog’ |

a55ɲie53tli55 ‘bitch’ |

ŋa11tli55 ‘puppy’ |

|

a55tʂhɥ11 ‘cat, tomcat’ |

a55ɲie53a55tʂhɥ11 ‘queen’ |

ŋa11a55tʂhɥ11 ‘kitten’ |

|

qai55 ‘chicken, cock’ |

a55ɲie53qai55 ‘hen’ |

ŋa11qai55 ‘chick’ |

|

o11 ‘duck, drake’ |

a55ɲie53o11 ‘(female) duck’ |

ŋa11o11 ‘duckling’ |

|

ŋɦu11 ‘goose, gander’ |

a55ɲie53ŋɦu11 ‘(female) goose’ |

ŋa11ŋɦu11 ‘gosling’ |

|

tlai11 ‘bear, boar’ |

a55ɲie53tlai11 ‘she-bear, sow’ |

ŋa11tlai11 ‘small bear, cub’ |

|

fɯ44 ‘wolf, dog’ |

a55ɲie53fɯ44 ‘she-wolf, bitch’ |

ŋa11fɯ44 ‘wolf puppy’ |

|

nau31 ‘bird, cock’ |

a55ɲie53nau31 ‘female bird, hen’ |

ŋa11nau31 ‘bird poult, chick’ |

|

li44fau44 ‘head’ |

a55ɲie53li44fau44 ‘big leader’ |

ŋa11li44fau44 ‘sub-leader’ |

|

tey44 ‘foot’ |

a55ɲie53tey44 ‘big toe’ |

ŋa11tey44 ‘little toe’ |

|

dɦi11 ‘hand’ |

a55ɲie53dɦi11 ‘thumb’ |

ŋa11dɦi11 ‘pinkie, little finger’ |

|

ŋgɦa35 ‘house’ |

a55ɲie53ŋgɦa35 ‘big house’ |

ŋa11ŋgɦa35 ‘cottage, small house’ |

|

a11dɦɯ11 ‘wall’ |

a55ɲie53a11dɦɯ11 ‘broad wall’ |

ŋa11a11dɦɯ11 ‘small wall’ |

|

tɕa44 ‘wind’ |

a55ɲie53tɕa44 ‘storm’ |

ŋa11tɕa44 ‘breeze of wind’ |

|

naɯ53 ‘rain’ |

a55ɲie53naɯ53 ‘heavy rain’ |

ŋa11naɯ53 ‘drizzle’ |

|

ʈau55 ‘mountain’ |

a55ɲie53ʈau55 ‘big mountain’ |

ŋa11ʈau55 ‘hill’ |

|

dlɦi35 ‘river’ |

a55ɲie53dlɦi35 ‘big river’ |

ŋa11dlɦi35 ‘brook’ |

|

tɕi55 ‘road’ |

a55ɲie53tɕi55 ‘esplanade’ |

ŋa11tɕi55 ‘alley’ |

|

au55 ‘water’ |

a55ɲie53au55 ‘big stream’ |

ŋa11au55 ‘runnel’ |

|

dʑɦi11 ‘street’ |

a55ɲie53dʑɦi11 ‘big street market’ |

ŋa11dʑɦi11 ‘small market’ |

|

zɦo11 ‘village’ |

a55ɲie53zɦo11 ‘big village’ |

ŋa11zɦo11 ‘small village’ |

Table 20: The scope of the two Ahmao prefixes

In Ahmao noun phrases, a process of metanalysisFor this notion see Campbell (1998: 103) or Trask (1996: 103).

Campbell, L., 1998 Historical linguistics: An introduction to its principles and procedures. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Trask, R. L., 1996, Historical Linguistics. London: Edward Arnolds Publishers. regrouped the size prefixes with the classifiers. Instead of viewing the size morphemes as prefixes of the noun, native speakers regarded them as suffixes of the classifier. This shift is illustrated in (3) and (4).

|

(3) |

a. |

tu44 |

a55 ɲie53- |

tli55 |

|

|

b. |

tu44 |

-a55 ɲie53 |

tli55 |

|

|

|

|

CL |

AUG |

dog |

|

|

|

|

CL |

AUG |

dog |

| ‘the bitch’ | ‘the bitch’ | ||||||||||

|

(4) |

a. |

tu44 |

ŋa11- |

tli55 |

|

|

b. |

tu44 |

-ŋa11 |

tli55 |

|

|

|

|

CL |

DIM |

dog |

|

|

|

|

CL |

DIM |

dog |

| ‘the puppy’ | ‘the puppy’ | ||||||||||

The re-analyzed prefixed quickly merged with the classifiers by undergoing a process ofFor the notions of aphaeresis, syncope and apocope, see Campbell (1998: 31) or Trask (1996: 68).

Campbell, L., 1998 Historical linguistics: An introduction to its principles and procedures. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Trask, R. L., 1996, Historical Linguistics. London: Edward Arnolds Publishers. aphaeresis (loss of an initial segment), syncope (loss of a medial segment), as well as apocope (loss of a final segment). To illustrate, the animate classifier tu44 developed secondary forms tai44 and ta44.

|

Kind of Prefix |

Phase 1 |

Sound Change |

Phase 2 |

Sound Change |

Phase 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Augmentative: |

C*V* + a55 ɲie53 |

|

C*V* + ai |

|

C*ai |

|

Diminutive: |

C*V* + ŋa11 |

|

C*V* + a |

|

C*a |

Table 21: Merger of the size prefixes

The [ai]-versions of the classifiers that categorize animal nouns prefixed by a55ɲie53 were reinterpreted as female gender classifiers. The [ai]-forms of classifiers categorizing inanimate nouns were re-analyzed as augmentative size classifiers. Somewhat similarly, the [a]-forms which were reinterpreted as ‘offspring’ classifiers when categorizing animal nouns prefixed by ŋa11. The merged classifiers acquired additional pragmatic senses. The [ai]- and [a]-forms initially encoded the gender/age of noun referents, but subsequently shifted them to marking the gender/age of the speaker. The [ai]-classifiers index female speakers and [a]-classifiers child speakers.

(2) Definite/indefinite split. Numeral constructions in which indefinite classifiers are adjacent to numerals are the initial environment for the definite/indefinite drift. The definite/indefinite split surfaced through morphological reanalysis of the glottal suffix [ʔ] in the numeral *iʔ ‘one.’ Within this process, the glottal stop [ʔ] was viewed as part of the following classifier with which it underwent sound changes.

The high tone of the numeral one imposes a sandhi tone on the classifier either [33] or [31] in most casesSee Wang Fushi (1957), Wang Fushi and Wang Deguang (1986) and especially Gerner and Bisang (2010).

Wáng Fǔshì 王辅世, 1957, The classifier in the Wēiníng dialect of the Miao language 贵州威宁苗语量词. Yǔyán Yánjiū 语言研究, 75-121.

Wáng Déguāng 王德光 (1987). Additional remarks on the classifiers of the Miao language in Wēiníng county. 贵州威宁苗语量词拾遗. Mínzú Yǔwén 民族语文 5: 36-39.

Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2010, Classifier declinations in an isolating language: On a rarity in Wēiníng Ahmao. Language and Linguistics 11(3): 576-623. Taibei: Academia Sinica.. For some of the ca. 50 classifiers, the sound changes ceased at this point. The sandhi tone classifiers were reinterpreted as indefinite classifiers. The sound changes went further for other classifiers. In AhmaoSee Johnson, M., 1999, Tone and phonation in Western A-Hmao. SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 9: 227-251. and Green HmongSee Andruski, J. and M. Ratliff, 2000, Phonation types in production of phonological tone: The case of Green Mong. Journal of International Phonetic Association 30.37-61., sandhi tone and phonation type have a close relationship (which is also attested in the Ahmao data). In numeral-classifier compounds, *i ‘one’ not only imposed sandhi tones on the classifier, but also transferred its phonation type to the classifier. Classifiers with voiceless initial consonant had its phonation switch to voicing, and classifiers with voiced initial consonant changed its phonation to breathy voicing. These three types of changes (sandhi tone, voicing, and breathy voicing) represent all the changes that have been observed in Ahmao classifiers. Classifiers were reinterpreted as indefinite articles in the contexts within which they underwent these sound changes. They were understood as definite classifiers in the other contexts.

|

(5) |

a. |

* |

i |

la53 |

ʈau55 |

|

b. |

i55 |

la35 |

ʈau55 |

(tone sandhi) |

|

|

|

|

|

NUM.1 |

CL.DIM |

hill |

|

|

|

NUM.1 |

CL.DIM |

hill |

|

| ‘one hill’ | ‘one hill’ | |||||||||||

|

(6) |

a. |

* |

i |

tai44 |

ɲɦu35 |

|

|

b. |

i55 |

dai213 |

ɲɦu35 |

(voicing) |

|

|

|

|

NUM.1 |

CL.MED |

ox |

|

|

|

NUM.1 |

CL.MED |

ox |

|

| ‘one ox’ | ‘one ox’ | |||||||||||

|

(7) |

a. |

* |

i |

dla53 |

ndlɦaɯ35 |

|

|

b. |

i55 |

dlɦa53 |

ndlɦaɯ35 |

(breathy voicing) |

|

|

|

|

NUM.1 |

CL.AUG |

picture |

|

|

|

NUM.1 |

CL.AUG |

picture |

|

| ‘one picture’ | ‘one picture’ | |||||||||||

In HmuData in this section are quoted by Gerner, M., 2017, Specific classifiers versus unspecific bare nouns. Lingua 188: 19-31., a Central Miao language spoken around Kǎilǐ city in Guìzhōu province, the use of bare classifiers (classifiers and nouns) contrasts with the use of bare nouns. Bare classifiers (BCL) encode specific reference, while bare common nouns (BN) express unspecific reference. In the discourse context, we understand specific versus unspecific reference as the properties of picking out one versus not-one referents.

(A) Introduction

In East Asian languages, classifiers do not have independent grammatical functions but contribute to marking the functions of counting (with numerals), quantification (with quantifiers), or deixis (with demonstratives). The languages generally contain one plural and mass classifier, whereas all other classifiers count the singular number of the noun that they modify. When bare classifiers are available, they usually encode indefinite reference, definite reference, or both, contingent upon the syntactic position in which they are used. Similarly, bare nouns feature definite, indefinite or generic reference depending on the slot in which they occur. Examples (8)-(9) illustrate the range of functions that bare classifiers and bare nouns are able to express. Bare classifiers have been exemplified in (8), bare nouns in (9). Ambiguous interpretations can be clarified by way of contextual information.

|

|

|

KamKam is a Tai-Kadai language spoken by about one million people in China. Example (8a) is sourced from the fieldwork of Matthias Gerner. (indefinite BCL) |

|

|

AhmaoAhmao is a Miao-Yao language used by 350,000 speakers in Wēiníng 威宁 county of Guìzhōu province in China. Example (8b) is quoted from Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2008, Inflectional Speaker-Role Classifiers in Wēiníng Ahmao. Journal of Pragmatics 40(4), 719-732. (definite BCL) |

||||||

|

(8) |

a. |

yaoc |

semh |

mungx |

nyenc. |

|

b. |

ɳɖau31ʂə55naɯ55 |

dzɦo35 |

tu44 |

mpa33zau55. |

|

|

|

1.SG |

look for |

BCL |

person |

|

|

Daushenau |

follow |

BCL |

wild boar |

| ‘I am looking for someone.’ (Specific/unspecific) | ‘Daushenau followed the wild boar.’ | ||||||||||

|

|

|

Chinese (indefinite/definite/generic BN) |

|||||||||

|

(9) |

a. |

tā |

hē |

jiŭ. |

|

b. |

tā |

bă |

jiŭ |

màn-màn- de |

hē diao. |

|

|

|

3P.SG |

drink |

BN:wine |

|

|

3P.SG |

COV |

BN:wine |

slowly-ADVL |

drink |

| ‘He drinks wine.’ (Indefinite and generic) | ‘He drinks [his] wine slowly.’ (Definite) | ||||||||||

Dedicated markers of un/specificity are cross-linguistically rare. More common are forms encoding the notion of (un)specificity in conjunction with other grammatical concepts. TurkishSee Enç, M., 1991, The Semantics of Specificity. Linguistic Inquiry 22: 1-25., for example, exhibits differential object marking triggered by specific noun phrases. HindiSee Mohanan, T., 1994, Arguments in Hindi. CSLI Publication, especially p. 104. uses two object markers, one of them on animate and specific noun phrases. The Turkish and Hindi markers of specificity are case markers in the first place, and not determiners. Hmu, by contrast, employs primary markers of specificity and the lack thereof. Hmu is typologically rare, even among the Miao-Yao languages, in encoding specific versus unspecific reference by employing a minimal pair of forms. Bare classifiers mark specific reference, while bare nouns unspecific reference. Example (10a) illustrates the bare classifier. The speaker is confined in a room and hears the barking of exactly one dog outside the house. He cannot see the dog and may or may not be familiar with it. The setting of (10b) is the same as in (10a) barring the number of dogs. The use of the bare noun entails the presence of at least two barking dogs.

|

Hmu |

|||||||||

|

(10) |

a. |

dail |

dlad |

jub |

naix |

wat. |

|||

|

|

|

BCL |

dog |

bark at |

people |

very |

|||

| ‘A/the dog is barking.’ (Specific meaning) | |||||||||

|

|

b. |

dlad |

jub |

naix |

wat. |

|

|

|

|

BN:dog |

bark at |

people |

very |

|

| ‘Dogs are barking.’ (Unspecific meaning) | ||||||

In the following subsections, we illustrate that Hmu bare classifiers and bare nouns have specific and unspecific reference, respectively and that bare nouns may further exhibit generic, universal and distributive reference, depending on the syntactic construction and discourse context. A noun phrase has generic reference if and only if (iff) almost all elements in its discourse extension have the noun phrase property. A noun phrase has universal reference iff all elements in its discourse extension have the noun phrase property. A noun phrase in the scope of an intensional predicate has distributive reference iff its discourse extension is the Cartesian product of the sets of referents indexed by suitable possible worlds.

(B) Unique Entities

Entities with unique existence do have specific reference not only in a discourse, but also in the physical world at large. Any form that imposes an unspecific interpretation on that entity results in an ungrammatical expression. In (11a), the unspecific reading for the bare noun ghab dab ‘Earth’ is ungrammatical in Hmu. The classifier laib must be used to indicate specific reference, as in (11b).

|

(11) |

a. |

* |

sangs lul |

id |

ax |

maix |

dail xid |

hsent |

hot |

ghab dab |

dios |

dlenx |

hul. |

|

|

|

|

ancient time |

DEM.FAM |

NEG |

have |

who |

believe |

say |

earth |

COP |

round |

EXCL |

| Intended meaning: ‘In ancient times, nobody believed that Earths are round.’ | |||||||||||||

|

|

b. |

sangs lul |

id |

ax |

maix |

dail xid |

hsent |

hot |

laib |

ghab dab |

dios |

dlenx |

hul. |

|

|

|

ancient time |

DEM |

NEG |

have |

who |

believe |

say |

BCL |

earth |

COP |

round |

EXCL |

| ‘In ancient times, nobody believed that the Earth is round.’ | |||||||||||||

The interpretation of a singleton extension is semantically encoded in the classifier and the sense of a non-singleton extension is part of the bare noun. The meaning of non-singleton extension cannot be cancelled, as shown in (11). Furthermore, bare nouns cannot be employed when the context imposes a singleton interpretation. If it is known that only one wedding took place, as seen in (12), it can be inferred that we must use the classifier. The omission of the classifier entails the presence of at least two weddings.

|

(12) |

a. |

* |

maix |

dangx-ngix-jud-yangl-niangb |

niangb |

Ghab Det Dlenx. |

|

|

|

|

have |

table-meat-wine-lead-wife |

at |

Gadedlen (village) |

| Intended meaning: ‘There is a wedding in Gadedlen.’ | ||||||

|

|

b. |

maix |

laib |

dangx-ngix-jud-yangl-niangb |

niangb |

Ghab Det Dlenx. |

|

|

|

have |

BCL |

table-meat-wine-lead-wife |

at |

Gadedlen (village) |

| ‘There is the wedding in Gadedlen.’ | ||||||

(C) Possessives

Possessives or partitives denote the association of entities with another entity. Classifiers are required for singleton possessees, as seen in (13)-(14), and possessees that exist in pairs, as evidenced in (15). Meanwhile bare nouns are ungrammatical in both cases.

|

(13) |

a. |

* |

ghet |

ghab niangx |

|

b. |

ghet |

laib |

ghab niangx |

|

|

|

|

grandfather |

age |

|

|

grandfather |

CL |

age |

| ‘Grandfather’s age’ | ‘Grandfather’s age’ | ||||||||

|

(14) |

a. |

* |

bib |

jid |

|

b. |

bib |

jox |

jid |

|

|

|

|

|

1.PL |

body |

|

|

1.PL |

CL |

body |

|

| ‘some of our bodies’ | ‘our body’ | |||||||||

|

(15) |

a. |

* |

wil |

hniongs mais |

|

b. |

wil |

jil |

hniongs mais |

|

|

|

|

|

1.SG |

eye |

|

|

1.SG |

CL |

eye |

|

| ‘some of my eyes’ | ‘my eye’ | |||||||||

Unique kinship relations are always specific and necessitate classifiers, whereas alienable human relationships have unique or anti-unique interpretations depending on the use of classifiers or bare nouns.

|

(16) |

a. |

* |

wil |

bad |

|

b. |

wil |

zaid |

bad |

|

|

|

|

1P SG |

father |

|

|

1P SG |

CL |

father |

| ‘*fathers of mine’ (Anti-unique) | ‘my father’ (Unique) | ||||||||

|

(17) |

a. |

wil |

ghab bul |

|

b. |

wil |

dail |

ghab bul |

|

|

|

1P SG |

friend |

|

|

1P SG |

CL |

friend |

| ‘some friends of mine’ (Anti-unique) | ‘my friend’ (Unique) | |||||||

The set of entities associated with something can be singleton (‘the age of a student’), dual (‘a leg of a student’), paucal (‘a corner of an intersection’), or multiple (‘a student of Oxford University’). Barker (2004)See Barker, C., 2004, Possessive Weak Definites. In J. Kim, Y. Lander, B. Partee, eds., Possessives and beyond: Semantics and Syntax, 89-113, University of Massachusetts at Amherst. coined the term ‘weak definites’ for paucal sets of associated things. When used with the English definite article the, weak definites indicate unique existence, not because the speaker is familiar with the referent, but because unique identification is guaranteed due to the small number of associated things. For the weak definite in (18a), the speaker does not have any particular corner in mind but promises easy identification; for the ordinary definite in (18b), he has one particular in mindExamples (18a) and (18b) are quoted from pp.89-90 of Barker, C., 2004, Possessive Weak Definites, in: J. Kim, Y. Lander, B. Partee, eds., Possessives and beyond: Semantics and Syntax, 89-113, University of Massachusetts at Amherst..

|

(18) |

a. |

I hope the cafe is located on the corner of a busy intersection. |

|

|

b. |

I hope the cafe is located on the corner near a busy intersection. |

For small sets of possessees such as the fingers on a hand, classifiers convey the idea of unique existence, but do not necessarily permit identification of the referent as the doesExample (20) is quoted from p.96 of Barker, C., 2004, Possessive Weak Definites, in: J. Kim, Y. Lander, B. Partee, eds., Possessives and beyond: Semantics and Syntax, 89-113, University of Massachusetts at Amherst. with weak definites. Whilst both nouns grammatical, they have anti-unique reference, as shown in (19a).

|

(19) |

a. |

nenx |

ghab dad bil |

|

b. |

nenx |

jil |

ghab dad bil |

|

|

|

3P.SG |

finger |

|

|

3P.SG |

CL |

finger |

| ‘some of his fingers’ (Anti-unique) | ‘his finger’ (Unique but not identifiable) | |||||||

|

(20) |

|

The baby’s fully-developed hand wrapped itself around the finger of the surgeon. |

(D) Simple clauses

In the case of simple clauses, the classifier always encodes unique existence of the referent, as shown in (21a). Bare nouns have anti-unique reference and, might implicate generic, distributive but never universal interpretations, depending on their syntactic position. In intransitive clauses, bare nouns do not have distributive reference, since they are beyond the scope of a quantifier. If (21b) is uttered as a general statement, the bare noun implicates a generic interpretation for dogs.

|

(21) |

a. |

dail |

dlad |

bit |

niangb |

gid gux… |

jub |

naix |

wat. |

|

|

|

CL |

dog |

lie |

at |

outside |

bark at |

people |

very |

| ‘A/the dog is lying outdoors…and is barking.’ (Unique) | |||||||||

|

|

b. |

dlad |

bit |

niangb |

gid gux… |

jub |

naix |

wat. |

|

|

|

|

dog |

lie |

at |

outside |

bark at |

people |

very |

|

|

i. ‘Dogs are lying outdoors… and are barking.’ (Anti-unique) ii. ‘Dogs lie outdoors… and bark.’ (Generic: True even if one dog lies indoors) |

|||||||||

In transitive clauses, object NPs are within the scope of subject NPs implicating a distributive besides an anti-unique interpretation. In (22a), the classifier has specific reference. The bare noun in (22b) has anti-unique reference and implicates distributive reference.

|

(22) |

a. |

Dol |

jib daib |

vangs |

dail |

xangs dud. |

|

|

|

CL |

child |

look for |

CL |

teacher |

| ‘The children look for a certain teacher.’ (Unique) | ||||||

|

|

b. |

Dol |

jib daib |

vangs |

xangs dud. |

|

|

|

CL |

child |

look for |

teacher |

|

i. ‘The children look for (at least two) teachers.’ (Anti-unique) ii. ‘The children look each for a (different) teacher.’ (Distributive) |

|||||

Bare mass nouns have an anti-unique reference. Mass terms talk about masses as though they are divisibleSee Bunt (1985: 45; 1979: 255).

Bunt, H., 1979, Ensembles and the formal semantic properties of mass terms, in: F. Pelletier, ed., Mass terms: Some philosophical problems, 279-294, Dordrecht: Reidel.

Bunt, H., 1985, Mass terms and model-theoretic semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.: “any part of something that is water is water”. Since bare mass nouns are divisible, they have anti-unique and as a result, unspecific reference. For example, any amount of wine that someone drinks can be divided into parts for which the sentence (23a) can be truthfully uttered. The mass classifier in (23b), on the other hand, denotes a contextually unique, and thus specific, amount of wine.

|

(23) |

a. |

nenx |

hek |

jud. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

drink |

wine |

| ‘He is drinking wine.’ (Anti-unique) | ||||

|

|

b. |

nenx |

hek |

dol |

jud. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

drink |

CL |

wine |

| ‘He is drinking the (or a certain amount of) wine.’ (Unique) | |||||

(E) Negation

For native Hmu speakers, it is the classifier that has always scope over the negator, not the other way round. Example (24) illustrates classifiers in subject and (25) in object position.

|

(24) |

|

dail |

ghet lul |

ax |

yangl |

bib |

mongl. |

|

|

|

|

CL |

old man |

NEG |

lead way |

1.PL |

go |

|

|

i. ‘The old man did not lead us the way.’ (∃!¬) ii. *‘It is not the case that there is one old man who leads us the way.’ (¬∃!) |

||||||||

|

(25) |

|

nenx |

ax |

bangd |

dail |

lid vud |

diot |

bib. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

NEG |

shoot |

CL |

sheep |

COV:to |

1.PL |

|

i. ‘He didn’t shoot the sheep for us.’ (∃!¬) ii. *‘It is not the case that there is one sheep that he shot for us.’ (¬∃!) |

||||||||

In the scope of the negator, Hmu bare nouns have anti-unique reference and can implicate generic but not universal reference. Bare nouns are illustrated in subject (26) and in object position (27).

|

(26) |

|

jib daib |

ax |

hek |

dol |

yenb. |

|

|

|

child |

NEG |

smoke |

CL |

tobacco |

|

i. ‘(At least two) children are not smoking.’ (Anti-unique) ii. ‘Children don’t smoke.’ (Generic: True even if there is one child who smokes.) |

||||||

|

(27) |

|

wil |

ax |

heib |

hab. |

|

|

|

1.SG |

NEG |

weave |

strawshoe |

|

i. ‘I have not weaved strawshoes.’ (Anti-unique) ii. ‘I do not weave strawshoes.’ (Generic: True, even if I’ve weaved one strawshoe.) |

|||||

(F) Matrix clauses

In Hmu, bare classifiers that can be found in complement clauses trigger de re construalsA de re construal of a noun phrase in the scope of an intensional predicate is a referent that exists outside the particular context of the predicate. A de re construal can be represented by the formula Ǝ!y □ φ(y) where □ represents the intensional predicate. of their sense of unique existence, whereas bare nouns only allow de dicto construalsA de dicto construal of a noun phrase in the scope of an intensional predicate is a referent that exists only inside the particular context of the predicate. A de dicto construal can be represented by the formula □ Ǝy φ(y) where □ represents the intensional predicate.. Their referents are potentially distributed over different possible worlds. Bare nouns are markers of the unspecific distributive type. (28a) reports a de dicto belief about the speaker’s potential purchase of jade stones. The bare noun jade stone is distributive with referents in different belief-worlds. If the speaker never bought jade stones, the presence of jade stone would be curtailed to these belief worlds.

|

(28) |

a. |

nenx |

hsent |

hot |

wil |

|

dot |

vib eb gad |

lol. |

|

|

|

3P.SG |

believe |

say |

1P.SG |

buy |

get |

jade stone |

come |

| ‘He believes that I buy jade stones.’ (Distributive) | |||||||||

The usage of the bare classifier laib allows a de re construal even if the speaker is unaware of the identity of that stone and had never bought any jade stone. In this case the jade stone has a unique existence, but the belief is false.

|

|

b. |

nenx |

hsent |

hot |

wil |

|

dot |

laib |

vib eb gad |

lol. |

|

|

|

3P.SG |

believe |

say |

1P.SG |

buy |

get |

CL |

jade stone |

come |

| ‘He believes that I bought the/a certain jade stone.’ (Unique) | ||||||||||

(29a) is said to the unique child and daughter of a couple. Since no boy was born, the bare noun (bold font) has only referents in different wish-worlds, as opposed to the world of the utterance. Its referents are distributed over wish-worlds within which the would-be boys are different personalities. Thus, the bare noun has distributive reference.

|

(29) |

a. |

mongx |

zaid |

bad |

jeb hvib |

hot |

mongx |

zaid |

mais |

yis |

daib dial. |

|

|

|

2P.SG |

CL |

father |

hope |

say |

2P.SG |

CL |

mother |

give birth to |

son |

| ‘Your father hoped that your mother would give birth to a boy.’ (Distributive) | |||||||||||

Suppose that (29b), the counterpart of (29a), is addressed to the unique brother of three sisters. Since the product of a creational process is specific only at the end of the process, this utterance is felicitously used only if the addressee signifies the de re construal of the classifier noun. It is as though the speaker attributes a prescient wish to the father. Yet, this construal is metalinguistic and unavailable to the father at the time he expressed the wish. Importantly, any de re construal in the world in which the father expressed the wish is deemed infelicitous.

|

|

b. |

mongx |

zaid |

bad |

jeb hvib |

hot |

mongx |

zaid |

mais |

yis |

dail |

daib dial. |

|

|

|

2P.SG |

CL |

father |

hope |

say |

2P.SG |

CL |

mother |

give birth to |

CL |

son |

| ‘Your father hoped that your mother would give birth to a certain boy (= you).’ (Unique) | ||||||||||||

In this section, we document the most important classifiers in four representative languages of the Miao group. The classifiers are cognate for the most part, but do differ in the range of classified nouns.

| Classifiers | HmongThe classifier data in Hmong, a Western Miao language spoken in Hékǒu 河口 county, were collected by Matthias Gerner in 2007. |

AhmaoThe Ahmao data (Wēiníng 威宁 county) were recorded in discussions between Wáng Déguāng and Matthias Gerner in 2005 and published in Gerner and Bisang (2008, 2009, 2010): Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2008, Inflectional Speaker-Role Classifiers in Wēiníng Ahmao. Journal of Pragmatics 40(4), 719-732. Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2009, Inflectional classifiers in Wēiníng Ahmao: Mirror of the history of a people. Folia Linguistica Historica 30(1/2), 183-218. Societas Linguistica Europaea. Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2010, Classifier declinations in an isolating language: On a rarity in Wēiníng Ahmao. Language and Linguistics 11(3), 576-623. Taibei: Academia Sinica. |

HmuThe Central Miao language Hmu has about 1,400,000 speakers in Southeast Guìzhōu 贵州. The data in this section were collected by Matthias Gerner during 2003-2007 and published in: Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2010, Classifier declinations in an isolating language: On a rarity in Wēiníng Ahmao. Language and Linguistics 11(3), 576-623. Taibei: Academia Sinica. |

Xong Xong is an Eastern Miao language spoken by 900,000 people in Húnán province. The data originate from Huāyuán 花垣 county were collected by Matthias Gerner during 2007 and published in: Gerner, M. and W. Bisang, 2010, Classifier declinations in an isolating language: On a rarity in Wēiníng Ahmao. Language and Linguistics 11(3), 576-623. Taibei: Academia Sinica. |

||

|

|

|

|

Definite | Indefinite |

|

|

| Animate |

|

Augmentative |

tu44 |

du31 |

|

|

|

(also for tools) |

to21 |

Medial |

tai44 |

dai213 |

tɛ11 |

(ʈu42)The form ʈu42 is restricted to a few inanimate instruments (e.g. ‘plough’), whereas the general animate classifier is ŋoŋ22. In addition, there is a prefix ta33 attached to most animal nouns only dropped in numeral constructions. This prefix is a former classifier that has been lexicalized and replaced by the classifier ŋoŋ22. |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

ta44 |

da35 |

|

|

|

Animate |

|

Augmentative |

--- |

--- |

|

|

|

|

--- |

Medial |

--- |

--- |

--- |

ŋoŋ22 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

--- |

--- |

|

|

|

Human |

|

Augmentative |

lɯ55 |

lɯ44 |

|

|

|

|

lən42 |

Medial |

lai55 |

lai213 |

lɛ55 |

le35 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

la53 |

la35 |

|

|

|

Male |

|

Augmentative |

tsɨ55Wēiníng Ahmao involves the classifier tsɨ55 solely for ‘man’, which is only declined in singular-definite forms and switches to lɯ44 for all other forms. |

(lɯ44) |

|

|

|

|

--- |

Medial |

tsai55 |

(lai213) |

--- |

--- |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

tsa53 |

(la35) |

|

|

|

Natural Pairs |

|

Augmentative |

tshai11 |

tshai11 |

|

|

|

(body parts, clothing) |

tshai33 |

Medial |

tshai11 |

tshai213 |

--- |

dʑɦa44 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

tsha11 |

tshai35 |

|

|

|

Natural Pairs |

|

Augmentative |

dʑi53In Ahmao, two classifiers for natural pairs exist to exhibit two different origins. The Ahmao classifier dʑi53 is in retreat with a few classifieds left. |

dʑi31 |

|

|

|

(body parts, clothing) |

--- |

Medial |

dʑai53 |

dʑai213 |

tɕi11 |

--- |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

dʑa53 |

dʑa35 |

|

|

|

Plants |

|

Augmentative |

faɯ55 |

faɯ44 |

|

|

|

|

--- |

Medial |

fai55 |

fai213 |

fhu35 |

--- |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

fa53 |

fa35 |

|

|

|

Plants |

|

Augmentative |

--- |

--- |

|

|

|

|

tʂau43 |

Medial |

--- |

--- |

--- |

tʂou35 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

--- |

--- |

|

|

|

Plants |

|

Augmentative |

--- |

--- |

|

|

|

|

--- |

Medial |

--- |

--- |

kəu35 |

ko44 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

--- |

--- |

|

|

| FlowersThe classifier tou55 / ʈə55 is attested in Hmong (Hékǒu) and Ahmao (Wēiníng) and is borrowed from the Chinese classifiers duŏ 朵 for clouds and flowers, implying that this classifier was borrowed early in Proto-Miao. |

|

Augmentative |

ʈə55 |

ʈə44 |

|

|

|

|

tou55 |

Medial |

ʈəai55 |

ʈəai213 |

--- |

ʈɯ44 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

ʈəa53 |

ʈəa35 |

|

|

|

Lengthy Objects |

|

Augmentative |

tso11 |

tso31 |

|

|

|

(grass, hair) |

tso31 |

Medial |

tsui44 |

tsui53 |

--- |

--- |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

tsua44 |

tsua35 |

|

|

|

Lengthy Objects |

|

Augmentative |

dʑa53 |

dʑɦa11 |

|

|

|

(river, road) |

--- |

Medial |

dʑai53 |

dʑɦa213 |

tɕo55 |

--- |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

dʑa53 |

dʑɦa35 |

|

|

|

Inanimate |

|

Augmentative |

lu55 |

lu33 |

|

|

|

(general classifier) |

lo43 |

Medial |

lai55 |

lai213 |

lɛ33 |

le35 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

la53 |

la35 |

|

|

|

Metals |

|

Augmentative |

thau11 |

thau11 |

|

|

|

(‘lump’) |

tho31 |

Medial |

thai11 |

thai213 |

tho13 |

dloŋ35 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

tha11 |

tha35 |

|

|

|

Tools |

|

Augmentative |

--- |

--- |

|

|

|

(with a handle) |

ʈaŋ43 |

Medial |

--- |

--- |

tiaŋ33 |

ʈən35 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

--- |

--- |

|

|

| Solid MassesThe classifier for solid masses conveys two meanings: ‘pound’ (500 gram), and ‘lump’. Both meanings are attested in Ahmao, whereas in Hmong and Xong only the second meaning is available. In Hmu, the cognate classifier ki35 has acquired the meaning ‘kind of’. |

|

Augmentative |

ki44 |

ki11 |

|

|

|

(‘pound’) |

ki44 |

Medial |

kiai11 |

kiai13 |

(ki35)The cognate classifier in Hmu, ki35, has a different meaning (‘kind of’) and categorizes a broad range of nouns. |

tɕi42 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

kia11 |

kia35 |

|

|

| VersatileThis classifier means ‘piece’ and categorizes a wide range of objects, such as solid materials, land, documents, etc. |

|

Augmentative |

dla53 |

dlɦa11 |

|

|

|

(‘piece’) |

tɬai24 |

Medial |

dlai55 |

dlai213 |

ɬei31 |

lei42 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

dla53 |

dla35 |

|

|

| LandscapeThis classifier for landscape means ‘piece’, ‘plot’ or ‘row’ and categorizes flat land, mountain chains and crops (with the connotation of ‘a plot of crops’). |

|

Augmentative |

tlau55 |

tlau44 |

|

|

|

(‘piece’, ‘plot’, ‘row’) |

plaŋ13 |

Medial |

tlai55 |

tlai213 |

tɕaŋ35 |

(tɕaŋ35)The Xong classifier tɕaŋ35 has shifted to categorize solid materials and to imply ‘lump’, ‘chunk’, rather than to become classifier for landscape. |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

tla55 |

tla35 |

|

|

|

Landscape |

|

Augmentative |

ʂey55 |

ʂey44 |

|

|

|

(‘side’, ‘edge’) |

ʂaŋ13 |

Medial |

ʂyai55 |

ʂyai213 |

(saŋ55)In Kǎilǐ Hmu, the classifier saŋ55 is cognate to the other forms, but has shifted its meaning to ‘layer’, ‘stratum’. |

--- |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

ʂya53 |

ʂya35 |

|

|

|

Places |

|

Augmentative |

qho55 |

qho44 |

|

|

|

|

qhau55 |

Medial |

qhai55 |

qhai213 |

(qha44)In Hmu, there is a cognate nominal form qha44, but it cannot occur in classifier constructions. | (qho35)In Xong, the cognate form qho35 is a noun prefix attached to a wide range of nouns; it may not be involved in classifier constructions. |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

qha55 |

qha35 |

|

|

|

Clothes & Cloth |

|

Augmentative |

pho55 |

pho11 |

|

|

|

|

phau43 |

Medial |

phai55 |

phai213 |

phaŋ33 |

phaŋ35 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

pha35 |

pha35 |

|

|

|

Plural & Masses |

|

Augmentative |

ti55 |

di31 |

|

|

|

|

tɛ31 |

Medial |

tiai55 |

diai213 |

to11 |

--- |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

tia55 |

dia55 |

|

|

|

Collections |

|

Augmentative |

ntʂha11 |

ntʂha11 |

|

|

|

(‘bunch’) |

tsha44 |

Medial |

ntʂhai11 |

ntʂhai213 |

--- |

ndʑha54 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

ntʂha11 |

ntʂha35 |

|

|

|

Collections |

|

Augmentative |

bey53 |

bɦey11 |

|

|

|

(‘heap’, ‘row’) |

peu13 |

Medial |

bai53 |

bai213 |

pə44 |

plɯ55 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

ba53 |

ba35 |

|

|

| LiquidsThis classifier is an old loanword from the Chinese standard measure word shēng 升 ‘liter’. |

|

Augmentative |

ʂə55 |

ʂə44 |

|

|

|

(‘liter’) |

ʂən44 |

Medial |

ʂiai11 |

ʂiai213 |

ɕhən33 |

ɕhan44 |

|

|

|

Diminuative |

ʂia11 |

ʂia35 |

|

|

Table 22: Cognate Classifiers in the Miao Group

The Miao languages use relatively large sets of adnominal demonstratives comprising of five to nine elements. The hallmark of all Miao languages is the existence of recognitional demonstratives whose function is to activate inactive as well as private information shared between the speaker and the addressee. The Hmong language uses an unusual subset of three positional demonstratives in order to locate an object in front, back or opposite the speaker. The Ahmao language uses four altitude demonstratives which help identify an object at higher, equal, and lower altitude than the speaker.

|

Deictic Centre |

Distance |

Other Features |

Type I |

Type II |

Type III |

||

|

|

|

|

(‘agglutinative’) |

(‘fusional’) |

(‘isolating’) |

||

|

|

HmongThe Western Miao language Hmong is spoken by 500,000 people, mainly in Yúnnán province. The data presented in this section originate from Hékǒu 河口 county, were collected by Matthias Gerner and published in: Gerner, M., 2009, Deictic features of demonstratives: A typological survey with special reference to the Miao group. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 54(1), 43-90. |

AhmaoAhmao is a Western Miao language spoken by 350,000 people in Wēiníng 威宁 county of Western Guìzhōu. The data of this section were recorded by Matthias Gerner in 2005-2007 and published in: Gerner, M., 2009, Deictic features of demonstratives: A typological survey with special reference to the Miao group. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 54(1), 43-90. |

QanouQanou is a central Miao language spoken by perhaps 350,000 people in Sāndū 三都 county of Guìzhōu province. The language is closely related to Hmu. The data are field data of Matthias Gerner and published in: Gerner, M., 2009, Deictic features of demonstratives: A typological survey with special reference to the Miao group. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 54(1), 43-90. |

HmuThe Central Miao language Hmu has about 1,400,000 speakers in Southeast Guìzhōu 黔东南. The data in this section were collected by Matthias Gerner during 2003-2007 and published in: Gerner, M., 2009, Deictic features of demonstratives: A typological survey with special reference to the Miao group. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 54(1), 43-90. |

XongXong belongs to the Eastern Miao group and is spoken by ca. 50,000 people. The Xong dialect represented in this section is from Huāyuán 花垣 county in Húnán province. The data were published in: Gerner, M., 2009, Deictic features of demonstratives: A typological survey with special reference to the Miao group. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 54(1), 43-90. |

||

|

Speaker |

proximal |

--- |

na44 |

ȵi55 |

no22 |

noŋ35 |

nən44 |

|

Speaker |

medial |

--- |

nteu24 |

vɦai35 |

|

|

|

|

Speaker |

distal |

--- |

o44 |

|

|

|

|

|

Speaker |

distal ++ |

--- |

-phua33- |

|

|

|

|

|

Adressee |

proximal |

--- |

ka44 |

|

ni44 |

nən35 |

ka44 |

|

Speaker & Addressee |

proximal |

--- |

|

|

mo44 |

moŋ35 |

a44 |

|

Speaker & Adressee |

distal |