Introduction

The Hmu in Kǎilǐ Manchu Painting of 1786 depicting the Hmu in Kǎilǐ, Guìzhōu (from ‘A Miáo Album’ ‘苗蛮图册页’, Asian Division, Library of Congress, USA).Miao 苗 refers to the name used by the Chinese during the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC) for non-Chinese groups residing in the Yangtze valley south of the Han areas. Notably, its etymology remains uncertain. During the first millennium AD, these groups were forced by the expansive Han population to migrate southward to what is currently known as the Hunan, Guìzhōu, Sichuan, and Yunnan provinces. After the 18th century AD, some Miao groups shifted out of China into other Southeast Asian countries, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Myanmar. In the aftermath of the Second Indochina War (1960-1975), about 100,000 ethnic Miao fled to the United States, France, and Australia in the wake of their alliance with anti-communist forces which lost the war.

The Hmu in Kǎilǐ Manchu Painting of 1786 depicting the Hmu in Kǎilǐ, Guìzhōu (from ‘A Miáo Album’ ‘苗蛮图册页’, Asian Division, Library of Congress, USA).Miao 苗 refers to the name used by the Chinese during the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC) for non-Chinese groups residing in the Yangtze valley south of the Han areas. Notably, its etymology remains uncertain. During the first millennium AD, these groups were forced by the expansive Han population to migrate southward to what is currently known as the Hunan, Guìzhōu, Sichuan, and Yunnan provinces. After the 18th century AD, some Miao groups shifted out of China into other Southeast Asian countries, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Myanmar. In the aftermath of the Second Indochina War (1960-1975), about 100,000 ethnic Miao fled to the United States, France, and Australia in the wake of their alliance with anti-communist forces which lost the war.

The Miao in China use various names to identify themselves: “Xong” in Hunan Province; “Ahmao”, “Hmu”, “Damu” in Guìzhōu Province; and “Hmong” in Sichuan and Yunnan Province. In the 1950s, the Chinese Government grouped these tribes into the Miao 苗 Nationality, one of the official 56 nationalities. Miao tribes outside of China refer to themselves the name of “Hmong” and reject the term “Miao” as nonindigenous. About 1.3 million Hmu or Black Miao people live in Southeast Guìzhōu and comprise the main group within the Miao 苗 Nationality of 9.6 million members.

Culture

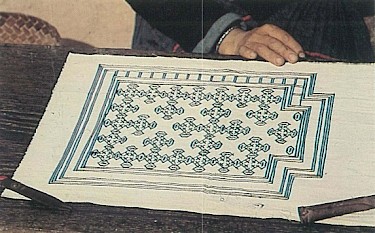

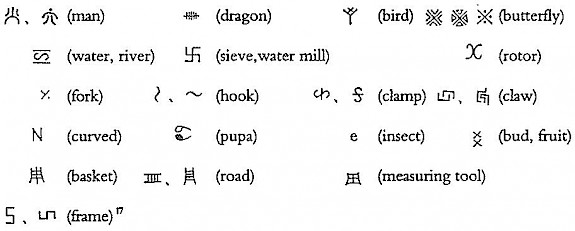

Native legends of the different Miao tribes mention about an ancient migration from a “cold land in the northSee Savina, F. M., 1924, Histoire des Miao. Paris: Société des Missions Etrangères.”. Meanwhile some myths mention an ancient indigenous script that the ancestors of the Miao lost during the process of forced migration. Remnants of this pictographic writing are said to be preserved in the sophisticated embroidery pattern of clothes and costumes. Miao intellectuals have identified nearly forty pictographic words within the embroidery design.

Miao EmbroiderySee Lewis, P., 1984, Peoples of the golden triangle. London: Thames and Hudson, p. 104.

Miao EmbroiderySee Lewis, P., 1984, Peoples of the golden triangle. London: Thames and Hudson, p. 104.

Embroidery writingSee Enwall, J., 1994, A myth become reality. History and development of the Miao written language. Volume 1 & 2. University of Stockholm.

Embroidery writingSee Enwall, J., 1994, A myth become reality. History and development of the Miao written language. Volume 1 & 2. University of Stockholm.

Deviant versions of the myth suggest that the ancient script was eaten by the Miao, which resulted in inner qualities such as ability to memorize the traditional songs. Some versions of this myth raise the expectation that the lost script would be resuscitated in the future. Pollard’s missionary script could capitalize on this expectation as the Ahmao in Western Guìzhōu viewed it as fulfilling the function the ancient writing once had.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Miao, primarily ancestors of the Hmu, mounted three rebellions in Guìzhōu Province against the imperial government, all of which resulted in defeat.

-

the First Miao Rebellion (1735-1738),

-

the Second Miao Rebellion (1795-1806) and

-

the Third Miao Rebellion (1854-1873).

Robert JenksSee Jenks, R., 1994, Insurgency and social disorder in Guìzhōu. The “Miao” Rebellion 1854-1873. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. relates the visceral motivations for the Miao to revolt against the three types of grievances: the alienation of ancestral land by Han merchants, excessive government taxation, and maladministration on the part of officials.

Second Miao Rebellion (1795-1806)Second Miao Rebellion in Guìzhōu and Húnán Provinces 1795-1806.Messianic expectations in the Miao folk religion might have accentuated the rebellious fervor as well. Jenks discusses the possibility that some Miao rebels may have been influenced by Han White Lotus sects (白莲教). Notably, these movements worship Maitreya, the future Buddha of Buddhist eschatology.

Second Miao Rebellion (1795-1806)Second Miao Rebellion in Guìzhōu and Húnán Provinces 1795-1806.Messianic expectations in the Miao folk religion might have accentuated the rebellious fervor as well. Jenks discusses the possibility that some Miao rebels may have been influenced by Han White Lotus sects (白莲教). Notably, these movements worship Maitreya, the future Buddha of Buddhist eschatology.

Besides the Miao, other ethnic minorities, Muslims, discontented Han, and religious folk sects joined the insurrections during which, by one account, almost five million people lost their lives. In addition, vast areas were depopulated.

The knowledge of these events remains ensconced in the collective memory of the Hmu people. Consequently, the Hmu have assimilated to the surrounding Han culture to a greater extent than, for example, the Ahamo in Western Guìzhōu, who did not participate in the rebellion. The Hmu society is an order comprising of about 20 clans of patrilineal lineage, each of which has its own name (e.g. Dliangx, Fangs). Babies are given native names at birth and additional Chinese names at the local registration office. The Hmu are strictly exogamous and intermarriage within a clan is prohibited. Membership to a clan is inherited through the male line. While unmarried women are members of the clan of their fathers, they become associated with the clan of their husbands after marriage.

Men blow the Lusheng in TáijiāngThe Hmu people grow paddy rice in the valleys in alternation with wheat or rape. Rice, maize, millet, and buckwheat are planted on the high terraced hillsides. Traditional houses are made of wood, have two to four storeys, and are roofed with either straw or bark. Most homes have a hearth but lack a chimney, thereby causing the house to be smoky.

Men blow the Lusheng in TáijiāngThe Hmu people grow paddy rice in the valleys in alternation with wheat or rape. Rice, maize, millet, and buckwheat are planted on the high terraced hillsides. Traditional houses are made of wood, have two to four storeys, and are roofed with either straw or bark. Most homes have a hearth but lack a chimney, thereby causing the house to be smoky.

Each village chooses a chief who is knowledgeable about the traditional customs and who may or may not be a Party Official. Typically, members of the same clan reside in the same village and gather for important social events. Since the year 2000, many young Hmu people have migrated to industrial areas in Guangdong in order to earn a living, while the elderly stay back home. The Hmu people are known to celebrate a number of festivals, primarily during the autumn, winter, and spring seasons:

-

Young women at the “Sister Festival”Lusheng Festivals (芦笙节) are dating events organized by groups of villages in the month of January, during which young men and women perform song competitions.

Young women at the “Sister Festival”Lusheng Festivals (芦笙节) are dating events organized by groups of villages in the month of January, during which young men and women perform song competitions. -

Sister Festivals (姊妹节) are events organized in the months of April and May, during which the Hmu women showcase their traditional decorative costumes.

-

Ancestor Festivals (牯藏节) are held every 13 years wherein a shaman slaughters an ox to officiate the communion between the members of a clan and the deceased ancestors.

-

Dragon Festivals (龙节) such as the Dragon Boat Festival or the Dragon Lantern Festival commemorate different folk myths: victory over a dragon that troubled the local community, or the invocation of protective forces of a benign dragon.

In Hmu society, songs serve the purpose of a medium of communication and self-expression. Groups of young men and women compete in multivocal songs at meetings, such as the Lusheng Festival. At such festivals, the Hmu people entertain relatives and visitors alike with copious amounts of liquor brewed from rice or maize.

Religion

(A) Traditional Religion: The Hmu believe in a creation myth, according to which a butterfly emerged from a maple tree, married a bubble, and then became pregnant. The butterfly laid twelve eggs whose cocoons were looked after by a bird. The hatched eggs subsequently became a Hmu man, the mythical ancestor Jiang Yang, a snake, a dragon, a buffalo, a tiger, an elephant, a thunder god, ghosts, as well as abstract phenomena such as disasters.

The Hmu Butterfly EpicThe Hmu folk religion is animism as opposed to polytheism. The term for god is wangx waix ‘heavenly king’, a relatively new term used in the New Testament of 1934. According to the beliefs espoused by the Hmu, the world is inhabited by good and evil spirits which they try to manipulate or seek protection from. Shamans reside in every village and mediate between lay individuals and the spiritual world. They often encode their esoteric knowledge in documents written in Chinese characters representing the Hmu sounds.

The Hmu Butterfly EpicThe Hmu folk religion is animism as opposed to polytheism. The term for god is wangx waix ‘heavenly king’, a relatively new term used in the New Testament of 1934. According to the beliefs espoused by the Hmu, the world is inhabited by good and evil spirits which they try to manipulate or seek protection from. Shamans reside in every village and mediate between lay individuals and the spiritual world. They often encode their esoteric knowledge in documents written in Chinese characters representing the Hmu sounds.

In their religion, every person has three souls that move to different places after the death. The first soul is buried in the grave with the dead body. The second soul stays in the village and supports the clan if old age is the cause of death. If the demise is caused by accident, the soul wanders around as an evil ghost, causing problems. Meanwhile the third soul returns to the ancestors if the person died under normal circumstances. The Shaman instructs the third soul to find its way to the place of the ancestors.

(B) Christianity: The China Inland Missionary Samuel Clarke克拉克 (1853-1946) commenced his missionary work among the Hmu people in 1895. Working with the native Hmu Christian Pān Xiùshān 潘秀山 in Guiyang during 1896, Clarke compiled a Miao language primer, a catechism, some tracts, and several hymns. In the same year, a mission station was established in Pánghăi 旁海, 20 kilometers to the north of Kăilĭ City 凯里市. Shortly after his appointment to Pánghăi in 1898, the China Inland Missionary William Fleming 明鑑光 (1867-1898) was murdered by Chinese who was opposed to the mission. The Hmu preacher Pān Xiùshān was also killed along with Fleming.

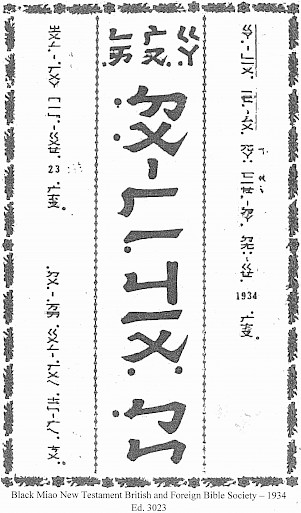

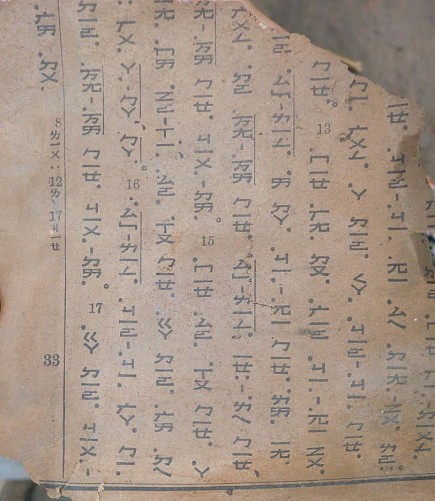

The Australian China Inland Missionary Maurice Hutton 胡致中 (1888-?) was appointed to Pánghăi in 1912. He invented the Chinese National Phonetic Script(注音字母) in 1920, a system inspired by Japanese kana and based on based on Chinese characters. Hutton published the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, a catechism, and a hymn book in 1928, and subsequently the entire New Testament in 1934. Hutton’s main Miao assistant was Wáng Xuéguāng 王学光. These books were printed in Zhīfú 芝罘, Shāndōng. However, no information is known about the number of printed Bible portions. Due to the turmoil of civil war between Nationalists and Communists and an epidemic of typhoid, the presence of missionaries in Pánghăi was discontinued for a long period of time. Hutton fled the invading Communists in 1936, before returning to Australia in 1938 after completing 26 years of service. However, the mission station in Pánghăi could not be maintained. Interest in Christianity declined in the 1950s. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1974), many copies of the New Testament were confiscated in house-to-house raids and eventually burnt.

Hmu New Testament, 1934

Hmu New Testament, 1934

Page of New Testament (1934)Page of New Testament (1934) found in Pánghăi in 2011.

Page of New Testament (1934)Page of New Testament (1934) found in Pánghăi in 2011.

Joakim EnwallSee Enwall, J., 1994, A myth become reality. History and development of the Miao written language. Vol. 1 and 2. University of Stockholm. compared the Ahmao in Western Guìzhōu and the Hmu in Southeast Guìzhōu for their varied reception of Christianity. For the year 1937, the number of baptized and literate Miao is displayed in the following chart.

|

|

AhmaoThe Pollard script of the Ahmao people had become accepted and was used even by many non-Christians. |

HmuEnwall estimates that about 50 people still knew Hutton’s writing in 1990. |

|---|---|---|

|

Baptized Christians in 1937 |

18,300 |

134 |

|

Literacy in missionary script in 1937 |

34,500 |

100 |

Table 1: Comparison of Ahmao and Hmu

He attributes the difference to three factors. First, the Hmu people had been in contact with Han settlers since the 18th century, whereas the Ahmao populated a barren mountain area and did not have much exposure to the Han. This difference prompted the Hmu desiring relative assimilation and the Ahmao to aspire for relative autonomy. The Hmu were not receptive to Christianity like the adjacent Han, whereas the Ahmao welcomed Christianity, unlike their Han neighbors.

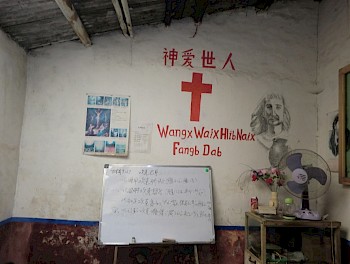

Hmu Christian meeting point in 2011Second, the ancient Miao myths of a lost script played a key role in the Ahmao society, but assumed less significance in the Hmu society. While the Ahmao embraced the Pollard script as the symbolic return of a lost treasure, the Hmu did not perceive the Hutton script in the same way. Third, the Hutton script is an extension of the Bopomofo, the phonetic script used for Mandarin Chinese prior to 1949, whereas the appearance of the Pollard script is different from other writing systems and can be viewed as an indigenous script.

Hmu Christian meeting point in 2011Second, the ancient Miao myths of a lost script played a key role in the Ahmao society, but assumed less significance in the Hmu society. While the Ahmao embraced the Pollard script as the symbolic return of a lost treasure, the Hmu did not perceive the Hutton script in the same way. Third, the Hutton script is an extension of the Bopomofo, the phonetic script used for Mandarin Chinese prior to 1949, whereas the appearance of the Pollard script is different from other writing systems and can be viewed as an indigenous script.

Since the 1990s, Han and foreign missionaries have settled in Southeast Guìzhōu. The number of Hmu Christians and village churches has increased again. Yet, many of the underlying attitudes that existed in the 1930s continue to prevail.

The Research Foundation published a new translation of the Hmu New Testament in 2009 using the Government-sponsored Romanized script, which was followed by a revised version in 2018. A short sketch of the translation process is presented on this webpage.

Language

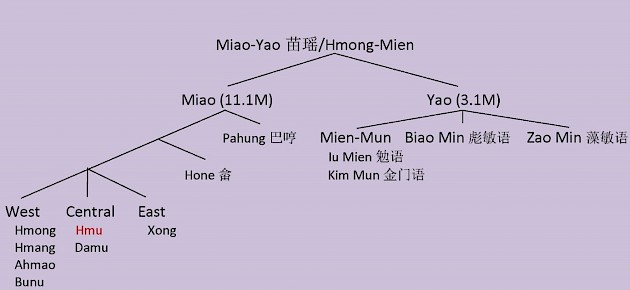

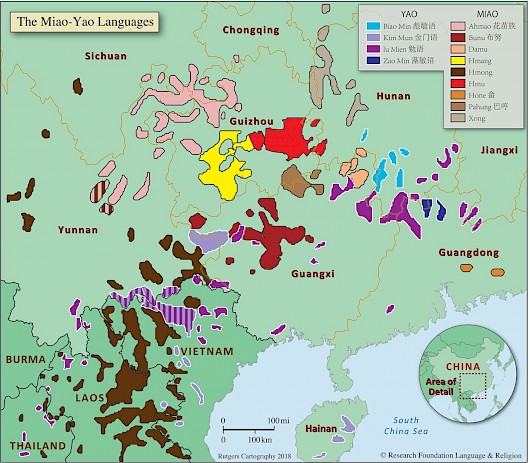

(A) General information: The Hmu belong to the Miao-Yao language family, which consists of about 80 languages. Martha RatliffSee Ratliff, M., 2010, Hmong-Mien Language History. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. classified the larger Miao-Yao languages as follows. They are partially renamed in the following diagram.

The terms Hmu and Qanao are identical. The Miao people in Guìzhōu use Hmu in a pan-Miao perspective, when comparing themselves to the Hmong in Yúnnán. In particular, they use Qanao in a regional perspective as a superordinate clan name. The geographic distribution of the Miao-Yao languages is illustrated on the following map.

The Miao-Yao languages are isolating languages and predominantly monosyllabic. Despite their structural similarity with Chinese and Tai-Kadai languages, they are genetically independent. Miao-Yao languages exhibit between six and eight contrastive tones, between 40 and 60 classifiers, and between five and eight demonstrative pronouns.

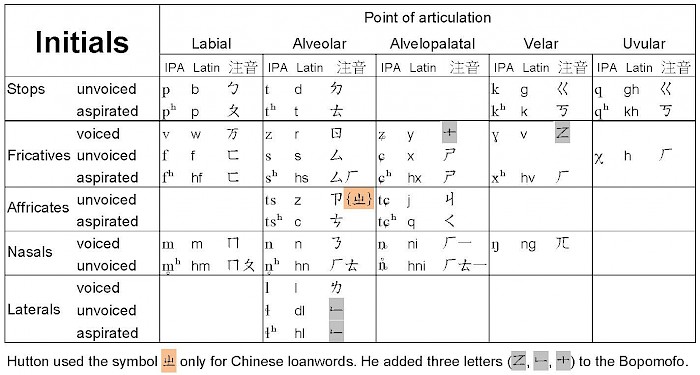

(B) Writing System: In 1913, the Bĕijīng Republican Government introduced the Bopomofo (注音符号), a system of 37 characters used for phonetic notation. The term Bopomofo is derived from the first four syllables (ㄅㄆㄇㄈ) in the conventional ordering of characters of that particular system. It was originally intended for dictionaries in order to show the standard Mandarin pronunciation. Maurice Hutton adopted the Bopomofo for transcribing the Hmu language and then extended it by three new symbols. The New Testament of 1934 has been edited in the extended Bopomofo. Joakim Enwall shows that the basis of Hutton’s script is a place in Huángpíng 黄平 County rather than Pánghăi where Hutton’s mission station was located.

In the 1950s, the Bĕijīng Communist Government dispatched investigation teams into the minority areas. In 1956, the committee for the Miao people chose the Yănghāo 养蒿 village, Guàdīng 挂丁 township, in Kăilĭ 凯里 City as the standard speech of the Hmu dialect of Miao. They devised a Romanized script for the speech in which numerous literacy campaigns were conducted, education materials were edited, and an indigenous literature was developed. The status of this script is semi-official. It falls short of being a generalized vehicle of bilingual education.

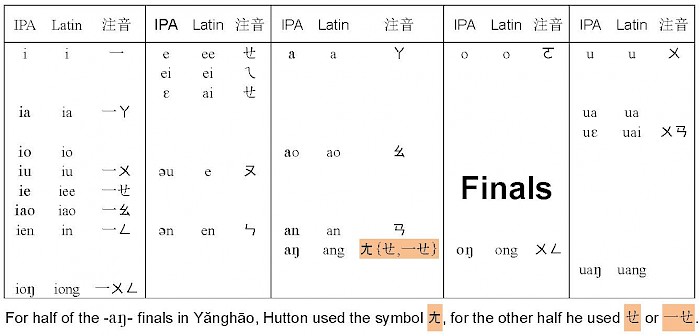

The Research Foundation published a new translation of the Hmu New Testament in 2009 using the Romanized script. Below we introduce the Hmu sound system and depict how each sound is encoded in the Romanized and Bopomofo scripts. There are 34 initials (consonants). The three-way contrast of voiced, unvoiced, aspirated fricatives and laterals is a typologically rare phenomenon among languages of the world.

There are 23 finals in the Yănghāo speech, six monophtongues, nine diphtongues, and one triphtongue. The finals -io-, - ua-, and - uang- do not have any counterpart in the speech chosen by Hutton.

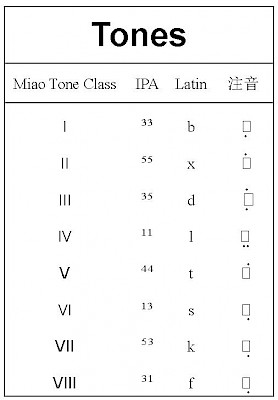

The eight contrastive tones of Hmu are associated with eight tone classes of Proto-Miao. In the IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet), tones are written with two-digit number superscripts, denoting the start and end of the tonal contour on a scale ranging from the pitch levels 1 (low) to 5 (high).

The eight contrastive tones of Hmu are associated with eight tone classes of Proto-Miao. In the IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet), tones are written with two-digit number superscripts, denoting the start and end of the tonal contour on a scale ranging from the pitch levels 1 (low) to 5 (high).

In the Romanized Hmu script, these eight tones are written with a silent final letter (e.g. -b, -t). Meanwhile in the Bopomofo script, the tones are written with super- or subscripts marked as points. Hutton only distinguishes six tones.

In the Romanized script, each syllable is written in accordance with the formula, [Initial + Final + Tone]. For example, the syllable niangb ‘located’ comprises of the initial ni-, of the final -ang- and the tone -b.

References

Bender, M. (2006). Butterfly Mother. Miao Creation Epics from Guìzhōu, China. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Corrigan, G. (2002). Guìzhōu Province. Costume and Culture in Remote China. Hong Kong: Airphoto International.

Enwall, J. (1994). A myth becomes reality. History and development of the Miao written language. Vol. 1 & 2. University of Stockholm.

Jenks, R. (1994). Insurgency and social disorder in Guìzhōu. The “Miao” Rebellion 1854-1873. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Lewis, P. (1984). Peoples of the golden triangle. London: Thames and Hudson.

Quincy, K. (1988). Hmong, history of a people. Cheney: Eastern Washington University Press.

Ratliff, M. (2010). Hmong-Mien Language History. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Savina, F. M. (1924). Histoire des Miao. Paris: Société des Missions Etrangères.

Wáng Míngdào 王明道 (1985). The History of the Gébù Church before Liberation 解放前葛布教会史. Historical materials on religion in Guìzhōu 贵州宗教史料,pp. 214-215.

Writing Committee of the Concise History of the Miáo People 苗族简史编写组 (1985). Concise History of the Miáo People 苗族简史。贵阳:贵州民族出版社。

Yàn Bǎo 燕宝 (1986). Checking Miáo family names and personal names 苗族姓氏人名考. Guìzhōu Literature and History Collection 贵州文史丛刊,Vol. 2, pp.47-48.