Some of the content on this page was published as

Gerner, M. (2015). “Yí 彝.” Encyclopedia of Chinese language and linguistics. General Editor R. Sybesma. Leiden: Brill.

Introduction

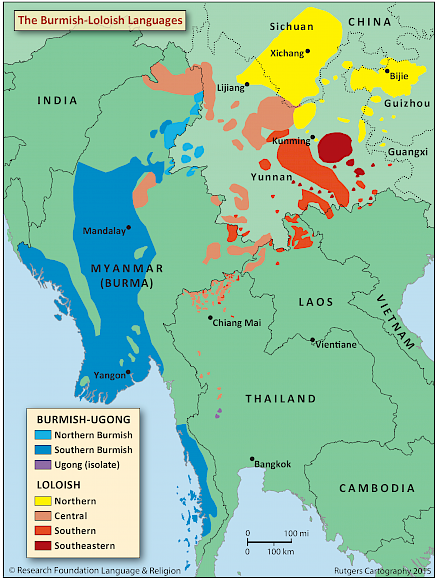

The Burmese-Lolo languages are divided into the Burmish and Loloish branch. Most Loloish languages are spoken by ethnic Yí 彝 people who constitute one of the 56 official nationalities in China. Ethnographic writers concur that the origin of most Loloish groups trace back more than 2000 years to an ancient group called Ni people. Steven HarrellSee Harrell (1995:76).

Harrell, S., 1995, The history of the history of the Yi, in: S. Harrell, ed., Cultural encounters on China’s ethnic frontiers, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 63-91., quoting the Chinese ethno-historiographer Mă Chángshoù 马长寿, believes that the earliest mention of the Yí is in historical accounts of the Zhou dynasty (1048-250 B.C.). Early Chinese records referred to Southwestern peoples as Wūmán 乌蛮 (Black Barbarians) and Báimán 白蛮 (White Barbarians). These names may point to the basic color labels applicable to virtually every minority in Southwest China, not only the Yi, but also other groups such as the Miao, Tai, Lahu, Lisu, etc. After the 12th century, Chinese sources gradually employed the name Lúo 猡 that contained the pejorative animal radical. The name subsequently evolved into its reduplicated form Lolo. This appellation was the designation used by Chinese and Westerners for several centuries until 1949 when, it was substituted by the name Yí 彝 with the arrival of the People’s Republic of China. In the language classification literature, Lolo survived within the language group designation Loloish languages.

Phylogenetics

The Burmese-Lolo languages belong to the Tibeto-Burman languages that are remote relatives of the Sinitic languages within the Sino-Tibetan family. The Burmese-Lolo languages are one of seven major language groups falling under the Tibeto-Burman nod. The name Tibeto-Burman derives from the most widely spoken of these languages: Burmese (32 million speakers) and Tibetan (8 million). The Tibeto-Burman languages comprise of more than 450 languages spoken in China, India, Myanmar, Nepal and Thailand as shown on the first map.

The Burmese-Lolo languages belong to the Tibeto-Burman languages that are remote relatives of the Sinitic languages within the Sino-Tibetan family. The Burmese-Lolo languages are one of seven major language groups falling under the Tibeto-Burman nod. The name Tibeto-Burman derives from the most widely spoken of these languages: Burmese (32 million speakers) and Tibetan (8 million). The Tibeto-Burman languages comprise of more than 450 languages spoken in China, India, Myanmar, Nepal and Thailand as shown on the first map.

According to scholarsSee Benedict, P. K., 1972, Sino-Tibetan: A conspectus, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

According to scholarsSee Benedict, P. K., 1972, Sino-Tibetan: A conspectus, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bradley, D., “Tibeto-Burman languages and classification”, in: D. Bradley, 1997, ed., Papers in Southeast Asian linguistics No.14: Tibeto-Burman languages of the Himalayas, pp. 1-72. Pacific Linguistics A-86, Canberra: Australian National University.

van Driem, G., 2001, Languages of the Himalayas, Vol 1 and 2, Leiden: Brill.

Matisoff, J., 2003, Handbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman. Berkeley. University of California Press.

Sūn, Hóngkāi 孙宏开, 1998, Twenty century research on Chinese minority languages and literature 二十世纪中国少数民族语言文字研究, edited by Liú Jiān 刘坚, Linguistics in China in the twenty century 二十世纪的中国语言学. pp. 641-682. Běijīng 北京: Běijīng University Publishing House 北京大学出版社. who have classified Tibeto-Burman languages, the Loloish languages constitute the principal component of the Burmese-Lolo language group. The majority of Loloish languages are spoken by ethnic Yí 彝 people who constitute one of the 56 official nationalities in China. Most scholars exclude Qiang, the extinct Tangut (西夏) language and Nung from Burmese-Lolo. Meanwhile Sūn, Hóngkāi 孙宏开See Sūn, Hóngkāi 孙宏开, 1998, Twenty century research on Chinese minority languages and literature 二十世纪中国少数民族语言文字研究, edited by Liú Jiān 刘坚, Linguistics in China in the twenty century 二十世纪的中国语言学. Běijīng 北京: Běijīng University Publishing House 北京大学出版社, 641-682. includes the Bai, Bisu and Tujia languages within the Yi (Loloish) group; these languages have been classified by Western scholars in other groups of Tibeto-Burman.

The Loloish languages have shared the same geographical area with Chinese for thousands of years. They are not inflectional like most other Tibeto-Burman languages. Instead, they have assimilated into Chinese with an isolating morphology.

During 1996-2013, we collected wordlists and grammar questionnaires from about 175 places. The data can be accessed through a separate interactive map on this websiteData points on this map are clickable and lead to the data..

Documentation

In this section we document some typologically outstanding properties of Burmese-Lolo languages. Most of these properties have been published in academic journals over the past few years.

The Loloish languages are characterized by a relatively high number of simple consonants, by the predominance of monophthongs and by tonal systems consisting of 3-5 tones.

Consonant systems of different Yi languages resemble each other and tend to exhibit large numbers of simple consonants, but only a few complex consonants. For example, there is a three-way contrast between voiced, voiceless, and aspirated stops for all three major points of articulation, i.e. bilabial, alveolar, and velar. Illustrations originate from LaloSee Björverud (1998:15-18).

Björverud, S., 1998, A grammar of Lalo, Ph.D. dissertation, Lund University. spoken in Wēishān 巍山 county.

|

Voiced |

[b]: |

ba33 |

‘bright’ |

[d]: |

da33 |

‘horny’ |

[g]: |

ga33 |

‘help’ |

|

Voiceless |

[p]: |

ʔna21pu55 |

‘ear’ |

[t]: |

ga55tu55 |

‘yard’ |

[k]: |

ku55 |

‘in’ |

|

Aspirated |

[ph]: |

phy55 |

‘sprinkle’ |

[th]: |

thy55 |

‘speak’ |

[kh]: |

khy55 |

‘gurgle’ |

Furthermore, there are several rare consonant patterns in the Yi group. For example, Liángshān Nuosu displays a bilabial voiced trill in its sound inventory represented as [ʙ]. It always occurs before the vowel [u] and sometimes with alveolar consonant onset as in [tʙ]. This trill is more pronounced in creaky syllables and/or with alveolar consonant onset.

|

|

[ʙ]: |

ʑi33ʙu44 |

‘roof’ |

[tʙ]: |

tʙu55 |

‘poison’ |

|

|

[ʙ]: |

ʙu55ʂə33 |

‘meadow’ |

[tʙ]: |

ʂɯ33tʙu33 |

‘steel’ |

The Neasu language spoken in Wēiníng 威宁 county (Guìzhōu) has an extensive set of retroflex consonants. The retroflex stops and nasal are particularly noteworthy.

|

Plosives |

[ɳɖ]: |

ɳɖɤ33 |

‘traverse’ |

[ɖ]: |

ɖɤ21 |

‘fly’ |

[ʈ]: |

ʈɤ55 |

‘weave’ |

[ʈh]: |

ʈhɤ55 |

‘leave over’ |

|

Africates |

[ɳɖʐ]: |

ɳɖʐa33 |

‘measure’ |

[ɖʐ]: |

ɖʐa21 |

‘import’ |

[ʈʂ]: |

ʈʂa33 |

‘support’ |

[ʈʂh]: |

ʈʂha33 |

‘should’ |

|

Nasals/Fricatives |

[ɳ]: |

ɳu55 |

‘event’ |

[ʐ]: |

ʐa55 |

‘forgive’ |

[ʂ]: |

ʂa33χɤ33 |

‘healthy’ |

|

|

|

The Nase language spoken in Luópíng 罗平 county (Yúnnán) has a double voicing alternation in the same consonant cluster. These oscillating clusters, which exist for the bilabial, alveolar and velar positions, consist of a voiced prenasal, a voiceless stop, as well as a breathy voicing release.

|

|

[mph]: |

mphɯ33 |

‘fell’ |

[nth]: |

nthɯ55 |

‘think’ |

[ŋkh]: |

ŋkhu21 |

‘door’ |

|

|

[mph]: |

mpha33 |

‘word’ |

[nth]: |

ntho33 |

‘drink’ |

[ŋkh]: |

ŋkho33 |

‘write’ |

Vowel systems are simple and basically comprise of monophthongs and sometimes of a few diphthongs, such as [iε] or [uɔ]. Most Yi languages we surveyed have unrounded central [ɨ] and back vowels [ɯ] or [ɤ] ([ɤ] are only attested in the Neasu language of Wēiníng 威宁 county in Guìzhōu). Most Yi languages have a contrast [i]-[ɪ] (e.g. Liángshān Nuosu) or [i]-[y] (e.g. Wēishān Lalo, Wēiníng Neasu).

All Yi languages have a stock of at least three contrastive tones: high [55], middle [33] and low [21] (sometimes [11]). Liángshān Nuosu has only three tones in addition to one sandhi-tone [44] which is not fully contrastive. On the other hand, Wēiníng Neasu and Mílè Axi have four and five contrasting tones, respectively. (Yi languages with sandhi-tones might be more numerous than those without.)

|

Liángshān Nuosu |

[55] |

[33] |

[21] |

|

(Sìchuān) |

bo55 ‘party’ |

bo33 ‘go’ |

bo21 ‘shine’ |

|

Wēiníng Neasu |

[55] |

[33] |

[21] |

[13] |

|

(Guìzhōu) |

ʈʂhu55 ‘spoiled’ |

ʈʂhu33 ‘car’ |

ʈʂhu21 ‘relatives’ |

ʈʂhu13 ‘sweet’ |

|

Mílè Axi |

[55] |

[33] |

[42] |

[22] |

[11] |

|

(Yúnnán) |

ni55 ‘fall over’ |

ni33 ‘dew’ |

ni42 ‘hungry’ |

ni22 ‘sit’ |

ni11 ‘ox’ |

The syllable structure in most Yi languages is relatively simple C(C)V(V)T (where T represents a suprasegmental tone). Syllables are open without nasal or obstruent closure. In addition to the regular modal phonation type, two other syllable types are widespread in the Yi group: creaky syllables and nasalized syllables. The emergence of the latter type can be attributable to Chinese loanwords. Syllables with nasal closure were borrowed from Chinese and progressively truncated into nasalized open syllables.

The Loloish languages contain some exceptional parts of speech that I succinctly sketch below. Several Loloish languages have definite articles. In Mílè Axi (Yúnnán) and Yǒngrén Lolo (Yúnnán), the general classifier, if deferred after the head noun N+CL, functions as definite article. In Liángshān Nuosu, definite articles are derived from classifiers by suffixing the nominalization particle -suSee Gerner, M., 2013, Grammar of Nuosu. MGL 64. Berlin: Mouton, pp. 160-165.. The bare classifier functions as an indefinite article.

|

|

|

Liángshān Nuosu |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) |

a. |

tsho33 |

ma33 |

|

b. |

tsho33 |

ma44su33 |

|

|

|

man |

CL |

|

|

man |

ART=CL+DET |

| ‘a man’ | ‘the man’ | ||||||

|

(2) |

a. |

ʙu33ȿə33 |

tɕi33 |

|

b. |

ʙu33ȿə33 |

tɕi44su33 |

|

|

|

snake |

CL |

|

|

snake |

ART=CL+DET |

| ‘a snake’ | ‘the snake’ | ||||||

Wēiníng Neasu (Guìzhōu) exhibits two definite articles which encode deictic information (close/far from speaker). These definite articles derive historically from the merger of demonstratives and the general classifier mo33. They included originally a medial definite article which further developed into a topic markerSee Gerner, M., 2003, Demonstratives, articles and topic markers in the Yi group, Journal of Pragmatics 35, 947-998.

Gerner, M., 2012a, Historical change of word classes. Diachronica 29(2), 162-200..

|

Determiner |

Proximal |

Medial |

Distal |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Demonstratives |

tha55 |

na55 |

ga55 |

|

Definite articles |

thɔ33 |

|

gɔ55 |

|

Topic marker |

|

nɔ33 |

|

Table 1: Determiners in Wēiníng Neasu

|

|

|

Wēiníng Neasu |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(3) |

a. |

hnu33tshɔ33 |

tha55 |

lə21 |

|

|

b. |

hnu33tshɔ33 |

thɔ33 |

|

|

|

person |

DEM:PROX |

CL |

|

|

|

person |

ART:PROX |

| ‘this person’ | ‘the person (close to speaker)’ | ||||||||

|

(4) |

a. |

hnu33tshɔ33 |

na55 |

lə21 |

|

|

b. |

hnu33tshɔ33 |

nɔ33 |

|

|

|

person |

DEM:MED |

CL |

|

|

|

person |

TOP |

| ‘that person (at medial distance)’ | ‘as for the person,…’ | ||||||||

|

(5) |

a. |

hnu33tshɔ33 |

ga55 |

lə21 |

|

|

b. |

hnu33tshɔ33 |

gɔ55 |

|

|

|

person |

DEM:DIST |

CL |

|

|

|

person |

ART:DIST |

| ‘that person (far away)’ | ‘the person (far away)’ | ||||||||

In the pronominal system, Liángshān Nuosu exhibits a rare African-style logophor with two suppletive forms: i33 (singular) and o21 (plural). In the narrow sense, a logophor is a proform that marks dependency on the speaker of a reported speech. Nuosu and MupunMupun is an Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Nigeria by 150,000 people and studied by

Frajzyngier, Z., 1993, A grammar of Mupun. Berlin: Reimer. exhibit logophors with this function. In the extended sense, a logophor codes dependency on a secondary speaker and additionally, on the person to whom an attitude, thought, or feeling is ascribed. The Chinese long-distance reflexive zìjĭ 自己See Huang, J. and Liu, L., 2001, Logophoricity, attitudes and ziji at the interface, in P. Cole, G. Hermon and C.-T. J. Huang, eds., Syntax and semantics 33, Long-distance reflexives, 141-195, New York: Academic Press. is a logophor in the broader sense. One feature of logophors in the narrow senseSee Huang, J. and Liu, L., 2001, Logophoricity, attitudes and ziji at the interface, in P. Cole, G. Hermon and C.-T. J. Huang, eds., Syntax and semantics 33, Long-distance reflexives, 141-195, New York: Academic Press. sense like that in Nuosu is that they need not be c-commanded详见 Gerner, M., 2016a, Binding and Blocking in Nuosu. The Linguistic Review 33(2), 277-307。 by their antecedents.

|

|

|

Liángshān Nuosu |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(6) |

a. |

ʂa33ma331 |

ṃ33ka552 |

tɕo44 |

hi21 |

ko33 |

i331/*2/*3 |

vu33 |

o44 |

di44. |

|

|

|

male name |

male name |

to |

say |

SENT-TOP |

LOG-SG |

crazy |

DP |

QUOT |

| ‘Shama1 told Muka2 that he1/*2/*3 became crazy.’ | ||||||||||

|

|

b. |

ṃ33ka551 |

ʂa33ma332 |

di44 |

ta33 |

gɯ33 |

hi21 |

ko33 |

o21*1/2/*3 |

vu33 |

o44 |

di44. |

|

|

|

male name |

male name |

at |

COV |

hear |

say |

SENT-TOP |

LOG-PL |

crazy |

DP |

QUOT |

| ‘Muka1 heard from Shama2 that they*1/2/*3 became crazy.’ | ||||||||||||

Liángshān Nuosu exhibits a particularly strong synesthetic sound symbolismFor this semiotic notion, see

Waugh, R. L., 1992, Let’s take the con out of iconicity: Constraints on iconicity in the lexicon. The American Journal of Semiotics 9. 7-48.

Waugh, R. L., 1994, Degrees of iconicity in the lexicon. Journal of Pragmatics 22. 55-70.. Prefixing i- to an adjectival root produces the diminutive member for a closed set of gradual antonym pairs, whereas prefixing a- to the same root yields the augmentative member.

|

[i] diminutive |

[a] augmentative |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

i44-ʂo33 |

‘short’ |

a33-ʂo33 |

‘long’ |

|

i44-tʙu33 |

‘thin’ |

a33-tʙu33 |

‘thick’ |

|

i44-ḷ33 |

‘light’ |

a44-ḷ33 |

‘heavy’ |

|

i44-dʑə33 |

‘narrow’ |

a33-dʑə33 |

‘wide’ |

|

i44-ȵi33 |

‘few’ |

a44-ȵi33 |

‘much, many’ |

|

i44-fu33 |

‘fine’ |

a33-fu33 |

‘coarse’ |

|

i44-nu33 |

‘soft’ |

a44-kɔ33 |

‘hard’ |

|

ɪ55-tsɨ33 |

‘small’ |

a44-ʑə33 |

‘big’ |

Table 2: Synesthetic sound symbolism in Liángshān Nuosu

The Loloish languages exhibit special types of syncretic and differential case marking. For clarification: case syncretismFor this notion see

Stolz, T., 1996, Some instruments are really good companions – some are not: On syncretism and the typology of instrumentals and comitatives. Theoretical Linguistics 23, 113-200.

Palancar, E., 2002, The origin of agent markers. Berlin: Akademieverlag, p. 41. is identical marking of different syntactic relations; differential case markingFor this notion see

Bossong, G., 1985, Differentielle Objektmarkierung in den Neuiranischen Sprachen, Gunter Narr Verlag, Tübingen. on the other hand, signifies different marking of the same syntactic relation. Differential subject/object marking (DSM/DOM) is reported in more than 300 languages worldwide. The factors that trigger DSM/DOM can be classified into four categories:

|

Type |

Category |

Trigger |

|---|---|---|

|

I |

Property of subject or object |

Animacy/definiteness/person of subject or object |

|

II |

Relationship between subject and object |

Their relative rank in animacyHuman ≻ Animate ≻ inanimate/definitenessPronoun ≻ proper noun ≻ definite ≻ specific ≻ nonspecific/personFirst/second ≻ third person-hierarchy |

|

III |

Relationship between subject, object, predicate |

Ambiguity of subject and object |

|

IV |

Property of relation between subject, object, predicate |

Tense, aspect, mood |

Table 3: Factors that trigger DSM/DOM

Burmese-Lolo exhibit languages of the trigger type I, III, IV. Subject marking in Mílè Azhee hinges on the subject’s animacy as well as on the ambiguity of subject and object (type I and III), whereas object marking in Yǒngrén Lolo depends on the ambiguity of subject and object alone (type III). The aspect of the whole clause (type IV) decides the subject marking in Gèjiù Nesu and the basic word order in Liángshān Nuosu.

DSM in Mílè AzheeAzhee is a Central Loloish language spoken by about 90,000 natives in Mílè 弥勒 county of Yúnnán Province (P.R. of China). For a detailed description, see

Gerner, M., 2016b, Differential subject marking in Azhee. Folia Linguistica 50(1), 137-173. Societas Linguistica Europaea. is triggered by the animacy of the subject (A) and also by potential A/O-ambiguity. It exhibits type I and III. Many Burmese-Lolo languages mark the subject on the basis of its animacy. Animacy-triggered DSM is sparsely attested in only 10% of the world’s languagesThis percentage is based on a typological investigation of 200 languages by Fauconnier (2011: 535). See

Fauconnier, S., 2011, Differential Agent Marking and animacy. Lingua 121. 533-547.. The Azhee case marker la55 marks either inanimate subjects or subjects that are ambiguous with objects; it does not mark other transitive subjects.

| Split (animacy, ambiguity) | ||

|

|

||

| Inanimate or ambiguous A |

|

Animate and unambiguous A |

|

A-la55 |

|

A-Ø |

The postposition la55 splits transitive clauses into sentences with inanimate and animate subjects. It marks one noun phrase as A, the instigating force. With zero marking, the sentence remains ungrammatical.

|

(7) |

a. |

lu33ho21 |

la55 |

go33mo33 |

|

tie21 |

bə55 |

wa55. |

|

b. |

* |

lu33ho21 |

|

go33mo33 |

|

tie21 |

bə55 |

wa55. |

||||||||||

|

|

|

hail |

DSM |

wheat |

|

hit |

collapse |

DP |

|

|

|

hail |

|

|

|

hit |

collapse |

DP |

||||||||||

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

|

V |

|

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

|

V |

|

|

|||||||||||

| ‘The hail destroyed the wheat.’ | Intended: ‘The hail destroyed the wheat.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Word order is free as long as the inanimate A is marked by la55, which can occur in the initial or second position.

|

(8) |

|

po33li21 |

mə55tə55 |

la55 |

tȿo33ʑe33 |

wa55. |

|

|

|

glass |

fire |

DSM |

melt |

DP |

| ‘The glass was melted by fire.’ | ||||||

The basic Azhee word order is unstable like in many other Loloish languages. Native speakers strongly prefer using the postposition la55 to disambiguate between the subject and object. The NP marked by la55 can occur in both the first and second position.

|

(9) |

a. |

a33ȿa55po55 |

a33nə33 |

bu21. |

|

b. |

a33nə33 |

a33ȿa55po55 |

bu21. |

|

|

|

male name |

female name |

carry |

|

|

female name |

male name |

carry |

|

|

|

A/O |

O/A |

V |

|

|

A/O |

O/A |

V |

| ‘Ashabo carried Anna.’ / ‘Anna carried Ashabo.’ | ‘Anna carried Ashabo.’ / ‘Ashabo carried Anna.’ | ||||||||

|

(10) |

a. |

a33ȿa55po55 |

la55 |

a33nə33 |

bu21. |

|

b. |

a33nə33 |

a33ȿa55po55 |

la55 |

bu21. |

|

|

|

male name |

DSM |

female name |

carry |

|

|

female name |

male name |

DSM |

carry |

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

V |

|

|

A |

O |

|

V |

| ‘Ashabo carried Anna.’ | ‘Ashabo carried Anna.’ | ||||||||||

DOM in Yǒngrén LoloLolo is a Central Loloish language spoken in Yǒngrén 永仁 county of Yúnnán Province (P.R. of China). For a detailed description, see

Gerner, M., 2008, Ambiguity-driven Differential-Object Marking in Yongren Lolo. Lingua 118, 296-331. is triggered by potential A/O-ambiguity and belongs to type III. The differential object marker thie21 splits direct objects into those that are ambiguous with the subject and those that are not. This marker is only used if the meaning of the predicate does disambiguate between the subject and the object. This marker cannot be used when the predicate disambiguates between the subject and object.

|

Split (ambiguity) |

||

|

Ambiguous O |

|

Unambiguous O |

|

O-thie21 |

|

O-Ø |

The basic word order of subject and object is free. Ambiguous clauses such as those in (11) can and should be disambiguated by the object marker thie21.

|

(11) |

a. |

ʐɔ21 |

ɕɛ33mo33 |

ʈȿhɔ33 |

ʑi33. |

|

b. |

ɕɛ33mo33 |

ʐɔ21 |

ʈȿhɔ33 |

ʑi33. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

snake |

follow |

go |

|

|

snake |

3.SG |

follow |

go |

|

|

|

A/O |

O/A |

V |

|

|

|

A/O |

O/A |

V |

|

| ‘He follows the snake./ The snake follows him.’ (For both a and b) | |||||||||||

|

(12) |

a. |

sɨ33ka55 |

χe33khɯ33 |

thie21 |

ti55 |

na33. |

|

b. |

sɨ33ka55 |

thie21 |

χe33khɯ33 |

ti55 |

na33. |

|

|

|

tree |

house |

DOM |

smash |

break |

|

|

tree |

DOM |

house |

smash |

break |

|

|

|

A |

O |

|

V |

|

|

A |

|

O |

V |

||

| ‘The tree smashed the house.’ | ‘The house smashed the tree.’ | ||||||||||||

The marker thie21 is also used to disambiguate between the subject (A) and the indirect object (B). Sentence (13a) without thie21 is ambiguous; sentence (13b) with thie21 is disambiguated.

|

(13) |

a. |

ŋo33 |

su55bə21 |

ʐɔ21 |

mo55. |

|

b. |

ŋo33 |

su55bə21 |

ʐɔ21 |

thie21 |

mo55. |

|

|

|

1.SG |

book |

3.SG |

show |

|

|

1.SG |

book |

3.SG |

DOM |

show |

|

|

|

A/B |

O |

B/A |

V |

|

|

A |

O |

B |

|

V |

|

‘I showed him a book./ He showed me a book.’ |

‘I showed him a book.’ | |||||||||||

DSM in Gèjiù NesuNesu is a Southern Loloish language spoken by about 20,000 natives in Gèjiù 个旧 city of Yúnnán Province (P.R. of China). For a description, see

Gerner, M., 2012b, Differential Subject Marking in Nesu. Paper presented at the International Conference Syntax of the World’s Languages 5, Dubrovnik, October 1-5, 2012. (Organizer: University of Zagreb). (and also Burmese) is triggered by the aspect of the clause and exhibits type IV. The Nesu particle ka55 marks subjects differentially in accordance with the aspect of the whole clause. The subject must be case-marked, if the simple clause encodes a resultative state; it can be case-marked if the clause is perfective without implying a result. It cannot be case-marked if the clause is imperfective. The Burmese marker káSee Jenny, M. and San San Hnin Tun, 2012, Differential Subject Marking in Colloquial Burmese. Paper presented at the SEALS XXII Conference, Agay (France), May 30 - June 2, 2012. exhibits similar properties as well.

|

Split (aspect) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Clause resultative |

Clause perfective but not resultative |

Clause imperfective |

||

|

A-ka55 |

A-(ka55) |

A-Ø |

||

The Nesu language has basic AOV order. The differential subject marker ka55 is obligatory in monotransitive clauses with resultative state. This is also applicable on subjects (A) that are animate, as in (14), or inanimate, as seen in (15).

|

(14) |

|

kə55 |

ka55 |

nu33mo21sɚ33 |

|

tsɨ33 |

a21mu21 |

thɛ21 |

wa33. |

|

|

|

|

3.SG |

DSM |

yellow bean |

|

grind |

powder |

become |

DP |

|

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

|

V |

|

|

|

|

| ‘He ground the yellow beans to a fine powder.’ | ||||||||||

|

(15) |

|

mu33hĩ33 |

ka55 |

hĩ21 |

|

pɛ21 |

pə33 |

|

wa33. |

|

|

|

|

wind |

DSM |

house |

|

blow |

collapse |

|

DP |

|

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

|

V |

|

|

||

| ‘The storm blew down the house.’ | ||||||||||

The subject can be optionally marked in clauses that are not resultative or imperfective. Example (16) shows a quantized event, whereas example (17) exhibits a bounded event. Furthermore, ditransitive subjects can be optionally marked by ka55, as evidenced in (18).

|

(16) |

|

kə55 |

(ka55) |

sɨ33 |

sɛ33 |

dzɚ55 |

|

dzɨ33 |

|

wa33. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

DSM |

tree |

NUM:3 |

CL |

|

fell |

|

DP |

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

|

V |

|

|

||

| ‘He fell three trees.’ | ||||||||||

|

(17) |

|

kə55 |

(ka55) |

hi21 |

go21 |

|

pi21khɚ55 |

|

wa33. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

DSM |

house |

door |

|

close |

|

DP |

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

|

V |

|

|

|

| ‘He closed the door.’ | |||||||||

|

(18) |

|

kə55 |

(ka55) |

ʑi21mo21 |

|

tshi33 |

|

ŋo33 |

|

dʑe21 |

wa33. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

DSM |

money |

|

lend |

|

1.SG |

|

COV:give |

DP |

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

|

V |

|

B |

|

|

|

| ‘He lent me money.’ | |||||||||||

The differential subject marker ka55 is prohibited in progressive transitive clauses, as seen in (19); in stative transitive clauses (20); and in intransitive clauses (21).

|

(19) |

|

kə55 |

(*ka55) |

thɛ33ɕe21 |

|

tshɨ33 |

dzɚ21. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

DSM |

clothes |

|

wash |

PROG |

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

|

V |

|

| ‘He is washing clothes.’ | |||||||

|

(20) |

|

ʑi21fɛ21 |

pho21 |

vi55la21 |

(*ka55) |

ʑi21 |

|

ŋɛ33tshɚ21. |

|

|

|

dry |

NOM |

flower |

SDM |

water |

|

need |

|

|

|

A |

|

O |

|

V |

||

| ‘The dry flower needs water.’ | ||||||||

|

(21) |

|

kə55 |

(*ka55) |

ŋɯ55 |

ɬi21ɬi21. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

DSM |

cry, weep |

IDE~ |

|

|

|

S |

|

V |

|

| ‘He is weeping bitterly.’ | |||||

The Liángshān NuosuNuosu is the principal language of the Yi Nationality. It is spoken by more than 2,000,000 natives in Liángshān 凉山 prefecture of Sìchuān Province (P.R. China). Nuosu is a Northern Loloish language. See Gerner (2004, 2013) for a detailed syntactic description and a grammar.

Gerner, M., 2004, On a partial, strictly word-order based definition of grammatical relations in Liangshan Nuosu. Linguistics 42, 109-154.

Gerner, M., 2013, Grammar of Nuosu. MGL 64. Berlin: Mouton. language incorporates the use of differential word order depending on the aspect of the whole clause. Nuosu exhibits type IV. The word order needs to be AOV, if the simple clause encodes a resultative state; it can be AOV or OAV if the clause is perfective without implying a result; on the other hand, it must be AOV if the clause is imperfective.

|

Split (aspect) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Clause resultative |

Clause perfective but not resultative |

Clause imperfective |

||

|

OAV |

AOV/OAV |

AOV |

||

Resultative clauses impose OAV order and either use resultative auxiliaries, as evidenced in (22)In example (22) which is quoted from Chen and Wu (1998: 230) the resultative auxiliary ko44ʂa33 ‘away’ is used. See

Chén Kāng 陈康 and Wū Dá 巫达, 1998, Yi grammar 彝语语法. Běijīng 北京: Zhōngyāng Mínzú Dàxúe Chūbănshè 中央民族大学出版社., O-oriented manner adverbs, as observed in (23), or by expressions of the form V1-si44-V2 (V1 is an activity verb, V2 is a directional verb), as illustrated in (24).

|

(22) |

|

ndʐə33 |

ṃ33 |

ndʐə33 |

ʑɔ55 |

si21 |

lo55tɕi33 |

tɕi33 |

ŋa33 |

|

dʑɔ33 |

ko44ʂa33 |

o44. |

|

|

|

wine |

do |

wine |

wrong |

CONJ |

finger |

CL |

1.SG |

|

fell |

SEND |

DP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O |

A |

|

V |

|

||

| ‘Because of the wine, I have cut off my finger.’ | |||||||||||||

|

(23) |

|

vi55ga33 |

gɯ44su33 |

a44mo33 |

tsɦɨ33 |

tɕhu44tsɨ33tsɨ33 |

o44. |

|

|

|

clothes |

ART (CL-DET) |

mother |

wash |

snow-white |

DP |

|

|

|

O |

A |

V |

|

|

|

| ‘The clothes were washed snow-white by Mum.’ | |||||||

|

(24) |

|

la21bu33 |

|

tshɨ33 |

hɯ33 |

-si44- |

bo33. |

|

|

|

ox |

|

3P SG |

borrow |

CONJ |

go |

|

|

|

O |

|

A |

V1 |

|

V2 |

| ‘He borrowed the ox.’ | |||||||

Thematic roles are not encoded for certain verbs in Nuosu. A bare predication with two human NPs is generally deemed ambiguous.

|

(25) |

|

a33ȵɔ33 |

ṃ33ko44 |

hɪ33vṵ33. |

|

|

|

female name |

male name |

love |

|

|

|

A/O |

O/A |

V |

| ‘Anyuo loves Mugo.’/or: ‘Mugo loves Anyuo.’ | ||||

Nuosu involves a grammatical tone on personal pronouns and certain verbs to disambiguate thematic roles. The [44]-sandhi tone is mainly the result of a rule [33]+[33] → [44]+[33] in a number of syntactic environments. With regard to the singular personal pronoun tshɨ33 which has the [33] tone in isolation, the [44]-sandhi tone has further acquired a grammatical meaning. It encodes the role of direct object, as demonstrated in (26). Moreover, a limited set of monosyllabic verbs have a tonal alternation [21]/[44] whereby the low tone imposes OAV order and the sandhi-tone requires AOV order, something that is illustrated in (27) for the verb ndu21/ndu44.

|

(26) |

a. |

a33ȵɔ33 |

tshɨ33 |

hɪ33vṵ33. |

|

b. |

a33ȵɔ33 |

tshɨ44 |

hɪ33vṵ33. |

|

|

|

female name |

3P SG |

love |

|

|

female name |

3P SG |

love |

| ‘He loves Anyuo’ | ‘Anyuo loves him.’ | ||||||||

|

(27) |

a. |

a33ȵɔ33 |

ṃ33ka55 |

ndu21. |

|

b. |

a33ȵɔ33 |

ṃ33ka55 |

ndu44. |

|

|

|

female name |

male name |

beat |

|

|

female name |

male name |

love |

| ‘Muka beats Anyuo.’ | ‘Anyuo beats Muka.’ | ||||||||

Imperfective clauses are marked by the progressive marker ndʑɔ33, as illustrated in (28), by the presence of agent- or verb-orientated manner adverbs, as evidenced in (29)Example (29) is quoted from Chen and Wu (1998:246)

Chén Kāng 陈康 and Wū Dá 巫达, 1998, Yí Grammar 彝语语法. Běijīng 北京: Central University of Nationalities 中央民族大学出版社., or by complex verbs of the form V1V2 (V1 is an activity verb, V2 is a directional verb), as seen in (30).

|

(28) |

|

a33ȵɔ33 |

ṃ33ka55 |

hɪ33vṵ33 |

ndʑɔ33. |

|

|

|

|

female name |

male name |

love |

PROG |

|

|

|

|

S |

O |

|

|

|

| ‘Anyuo loves Muga.’ | ||||||

|

(29) |

|

tsho33tɕho55a33ma55 |

ma33 |

ʐa44dʐa44dɯ33 |

ṃ33 |

sɨ33bo33 |

bo33 |

psɨ21 |

ko44 |

ŋga33 |

ʑə33 |

o44. |

|

|

|

sorceress |

CL |

curse |

ADVL |

tree |

CL |

carry |

there |

pass |

go down |

DP |

|

|

|

A |

ADV |

|

O |

V |

|

|

|

|

||

| ‘A sorceress, cursing carried a tree and passed by.’ | ||||||||||||

|

(30) |

|

tsɦɨ21 |

nʑi21 |

nɯ33 |

vz21vu33 |

i44ʑi33 |

di44 |

la21bu33 |

hɯ33 |

la33. |

|

|

|

Num.1 |

day |

TOP |

elder brother |

younger brother |

LOC |

ox |

borrow |

come |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

O |

V1 |

V2 |

| ‘One day, the elder brother came to borrow an ox from his brother.’ | ||||||||||

Bare verbs are a common phenomenon in Loloish languages and communicate ambiguous TAM (tense, aspect, and mood) meanings. Verbs are only marked for TAM concepts, and not for subject agreement. It is possible to suffix one, two, or three TAM particles to the verb. Standard TAM meanings expressed through these particles are perfect, progressive, experiential, and habitual aspect, future tense, epistemic, or deontic mood. We survey three exceptional particles below.

In Liángshān NuosuNuosu is spoken by more than 2,000,000 natives in Liángshān 凉山 prefecture of Sìchuān Province (P.R. China). Nuosu is a Northern Loloish language. See Gerner (2006) for a detailed description and formalization of the exhaustive aspect.

Gerner, M. (2006). The exhaustion particles in the Yi group: A unified approach to all, the completive and the superlative. Journal of Semantics 24, 27-72., the so-called exhaustion particle targets three types of structures: the clause-initial NP on which it acts as universal quantifier (‘all’), the VP which it modifies as completive marker (‘completely’), as well as the AP on which it contributes the meaning of superlative (‘most’). This marker assumes the form sa55.

|

(31) |

|

tsho33 |

hi55 |

ʑɔ21su33 |

thɯ21ʑə33 |

hɯ21 |

sa55. |

|

|

|

people |

NUM:8 |

ART (CL-DET) |

book |

see, read |

EXH |

| ‘The eight people are all reading books.’ | |||||||

|

(32) |

|

tsho21ɣo44 |

sɨ21hmi33 |

tshi33 |

ma33 |

dzɯ33 |

sa55 |

o44. |

|

|

|

3P PL |

nut |

NUM:10 |

CL |

eat |

EXH |

DP |

|

(i) ‘They all ate ten nuts.’ (ii) ‘They completely ate up ten nuts.’ (iii) ‘They all completely ate up ten nuts.’ |

||||||||

|

(33) |

|

i33ti44 |

a33dzɨ44 |

gu44 |

ndʐa55 |

sa55. |

|

|

|

garment |

DEM:DIST |

CL |

beautiful |

EXH |

| ‘That garment is the most beautiful.’ | ||||||

In Yǒngrén LoloLolo is a Central Loloish language spoken in Yǒngrén 永仁 county of Yúnnán Province (P.R. of China). The ambiperfective aspect is sketched in a paper by

Gerner, M., 2009a, The ambiperfective in Yongren Lolo. Paper presented at the 9th International Conference on Tense, Aspect and Modality, Denis Diderot University of Paris 7 (France), September 2-4, 2009., the sentence-final particle do55, termed ambiperfective particle, is used to convey imperfective (progressive) and perfective (completive) meanings, depending on the aspectual constitution of the clause. Table 4 depicted below provides an overview of the semantic contribution of the particle do55 to different types of underlying clauses.

|

Underlying Clause |

Contribution of ambiperfective do55 |

|---|---|

|

Punctual event |

Perfective |

|

Quantized event |

Perfective / Imperfective |

|

Bounded event |

Perfective |

|

Cumulative event |

Imperfective |

Table 4: The ambiperfective marker in Yǒngrén Lolo

Illustrations are given below. The ambiperfective particle, if appended to punctual events, conveys a (recent) perfective meaning, as seen in (34).

|

(34) |

|

ɔ55mɯ21lɔ33 |

tɦie21 |

ɔ55mɯ21ba21 |

tɦɯ21 |

lɔ33 |

do55. |

|

|

|

sky |

LOC |

flash |

exit |

come |

AMP |

| ‘A flash has (just) appeared in the sky.’ | |||||||

For quantized eventsThe term quantized events was coined by Krifka (1989, 1992, 1998). These are quantified events like eat three apples for which no proper subevent can again be of the type eat three apples.

Krifka, M., 1989, Nominalreferenz und Zeitkonstitution. Zur Semantik von Massentermen, Pluraltermen und Aspektklassen. Munich: Fink.

Krifka, M., 1992, Nominal reference, temporal constitution and thematic relations, in: Sag et al., eds., Lexical matters, Stanford: CSLI Publications, 29-53.

Krifka, M., 1998, The origins of telicity, in: S. Rothstein, ed., Events and grammar, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1998, 197-235., the ambiperfective particle do55 conveys both of its meanings: perfective as well as imperfective meaning, resulting in ambiguous sentences.

|

(35) |

|

ʐɔ21 |

ɔ55ɣo21 |

tɦɔ21 |

mo33 |

tɕɦɛ21 |

do55. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

song |

NUM.1 |

CL |

sing |

AMP |

|

(i) ‘She is singing a song.’ (ii) ‘She has just sung a song.’ |

|||||||

Bounded events satisfy the property of final stage closureThis property was first described by Krifka (1992) and Naumann (2001).

Krifka, M., 1992, Nominal reference, temporal constitution and thematic relations, in: Sag et al., eds., Lexical matters, Stanford: CSLI Publications, 29-53.

Naumann, R., 2001, Aspects of changes: A dynamic event semantics, Journal of Semantics 18, 27-81.. These are events such as walk to the station, for which each final stage again reflects an event of the type walk to the station. When appended to bounded events, the ambiperfective particle do55 switches to a perfective marker.

|

(36) |

|

ʐɔ21 |

dʑə21pɦi21 |

lɯ33 |

tʂo33 |

mɔ33 |

do55. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

money |

purse |

search |

perceive |

AMP |

| ‘She has just found her purse.’ | |||||||

Finally, for cumulative eventsThe term cumulative event was first introduced by Quine (1960). Cumulative events are events for which any extension is again of the same event type.

Quine, W., 1960, Word and object. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press. events, the Ambi-Perfective operator communicates an imperfective meaning; its perfective meaning is eclipsed.

|

(37) |

|

ʐɔ21 |

kɛ55ʑi33 |

do33 |

do55. |

|

|

|

3.SG |

sweat |

exit |

AMP |

| ‘He is sweating.’ | |||||

In Luópíng NaseNase is a Central Loloish language spoken in Luópíng 罗平 county of Yúnnán province (P.R. of China). For an analysis of two of the three particles, see

Gerner, M., 2009b, Assessing the modality particles of the Yi group in fuzzy possible-worlds semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy, 32, 143-184., three sentence-end particles are distinguished by tone alone. The particle di13 marks possible epistemic mood, the particle di55 marks necessary epistemic mood, and the particle di33 future tense.

|

TAM Concept |

Particle |

|---|---|

|

Possible Epistemic Mood |

di13 |

|

Necessary Epistemic Mood |

di55 |

|

Future Tense |

di33 |

Table 5: Sentence particles in Luópíng Nase

These particles have historically been derived from the verb ‘say’, but none of them can no longer function as a verb in modern speech. The epistemic modals have preserved a verb-like property, namely the option of negation (whereas the future particle di33 cannot be negated). (38a+b) and (39a+b) exemplify this interplay of negation and modals. The particle di33 is illustrated in (40) and is not required in order to express future tense, but always expresses future tense when it is present in the clause.

|

(38) |

a. |

POSS(φ): |

tʂɯ21 |

ni21nɔ55 |

pa55 |

na33 |

di13. |

|

|

|

|

|

3P SG |

younger sister |

busy |

very |

POSS |

|

| ‘His sister may be very busy.’ | ||||||||

|

b. |

¬NESS(¬φ): |

tʂɯ21 |

ni21nɔ55 |

ma21 |

pa55 |

na33 |

ma21 |

di55. |

||

|

|

|

3P SG |

younger sister |

NEG |

busy |

very |

NEG |

NESS |

||

| ‘His sister is not necessarily idle (not busy).’ | ||||||||||

|

(39) |

a. |

NESS(φ): |

tʂɯ21 |

ni21nɔ55 |

pa55 |

na33 |

di55. |

||

|

|

|

|

3P SG |

younger sister |

busy |

very |

NESS |

||

| ‘His sister must be very busy.’ | |||||||||

|

b. |

¬POSS(¬φ): |

tʂɯ21 |

ni21nɔ55 |

ma21 |

pa55 |

na33 |

ma21 |

di13. |

|

|

|

|

3P SG |

younger sister |

NEG |

busy |

very |

NEG |

POSS |

|

| ‘It is impossible that his sister is idle (not busy).’ | |||||||||

|

(40) |

|

FUT(φ): |

tʂɯ21 |

nu33bɯ33 |

di33. |

|

|

|

|

|

3P SG |

fall ill |

FUT |

|

| ‘He will fall ill.’ | ||||||

Sources

Björverud, S. (1998). A grammar of Lalo, Ph.D. dissertation. Lund University.

Bossong, G. (1985). Differentielle Objektmarkierung in den Neuiranischen Sprachen. Gunter Narr Verlag, Tübingen.

Chén Kāng 陈康 and Wū Dá 巫达. (1998). Yí Grammar 彝语语法. Běijīng 北京: Central University of Nationalities Press 中央民族大学出版社.

Fauconnier, S. (2011). Differential Agent Marking and animacy. Lingua 121. 533-547.

Frajzyngier, Z. (1993). A grammar of Mupun. Berlin: Reimer.

Gerner, M. (2003). Demonstratives, articles and topic markers in the Yi group, Journal of Pragmatics 35, 947-998.

Gerner, M. (2004). On a partial, strictly word-order based definition of grammatical relations in Liangshan Nuosu. Linguistics 42, 109-154.

Gerner, M. (2006). The exhaustion particles in the Yi group: A unified approach to all, the completive and the superlative. Journal of Semantics 24, 27-72.

Gerner, M. (2008). Ambiguity-driven Differential-Object Marking in Yongren Lolo. Lingua 118, 296-331.

Gerner, M. (2009a). The ambiperfective in Yongren Lolo. Paper presented at the 9th International Conference on Tense, Aspect and Modality, Denis Diderot University of Paris 7 (France), September 2-4, 2009.

Gerner, M. (2009b). Assessing the modality particles of the Yi group in fuzzy possible-worlds semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy, 32, 143-184.

Gerner, M. (2012a). Historical change of word classes. Diachronica 29(2), 162-200.

Gerner, M. (2012b). Differential Subject Marking in Nesu. Paper presented at the international conference Syntax of the World’s Languages 5, Dubrovnik, October 1-5, 2012. (Organizer: University of Zagreb.)

Gerner, M. (2013). Grammar of Nuosu. MGL 64. Berlin: Mouton.

Gerner, M. (2016a). Binding and Blocking in Nuosu. The Linguistic Review 33(2), 277-307.

Gerner, M. (2016b). Differential subject marking in Azhee. Folia Linguistica 50(1), 137-173. Societas Linguistica Europaea.

Harrell, S. (1995). The history of the history of the Yi, in: S. Harrell (ed.), Cultural encounters on China’s ethnic frontiers, pp. 63-91. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Huang, J. and Liu, L. (2001). Logophoricity, attitudes and ziji at the interface, in: P. Cole, G. Hermon and C.-T. J. Huang (eds.), Syntax and semantics 33 (Long-distance reflexives), pp. 141-195. New York: Academic Press.

Jenny, M. and San San Hnin Tun (2012). Differential Subject Marking in Colloquial Burmese. Paper presented at the Conference SEALS XXII, Agay (France), May 30 - June 2, 2012.

Krifka, M. (1989). Nominalreferenz und Zeitkonstitution. Zur Semantik von Massentermen, Pluraltermen und Aspektklassen, Munich: Fink.

Krifka, M. (1992). Nominal reference, temporal constitution and thematic relations, in: Sag et al. (eds.), Lexical matters, pp. 29-53. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Krifka, M. (1998). The origins of telicity, in: S. Rothstein (ed.), Events and grammar, 197-235. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Naumann, R. (2001). Aspects of changes: A dynamic event semantics, Journal of Semantics 18, 27-81.

Palancar, E. (2002). The origin of agent markers. Berlin: Akademieverlag.

Quine, W. (1960). Word and object, Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Stolz, T. (1996). Some instruments are really good companions – some are not: On syncretism and the typology of instrumentals and comitatives. Theoretical Linguistics 23, 113-200.

Sūn, Hóngkāi 孙宏开 (1998). 20th century research on Chinese minority languages and literature 二十世纪中国少数民族语言文字研究, in: Liú Jiān 刘坚 (ed.), Linguistics in China in the 20th century 二十世纪的中国语言学, pp. 641-682. Běijīng 北京: Běijīng University Press 北京大学出版社.

Waugh, R. L. (1992). Let’s take the con out of iconicity: Constraints on iconicity in the lexicon. The American Journal of Semiotics 9, 7-48.

Waugh, R. L. (1994). Degrees of iconicity in the lexicon. Journal of Pragmatics 22, 55-70.